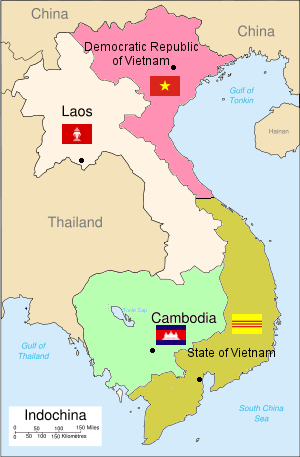

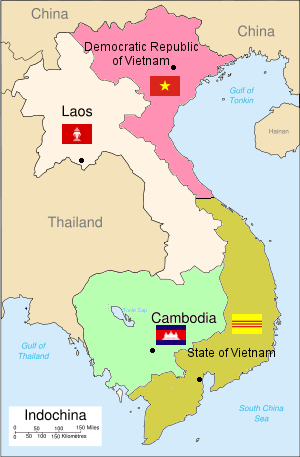

The Vietnam War was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. The north was supported by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, while the south was supported by the United States and other anti-communist allies. The war is widely considered to be a Cold War-era proxy war. It lasted almost 20 years, with direct U.S. involvement ending in 1973. The conflict also spilled over into neighboring states, exacerbating the Laotian Civil War and the Cambodian Civil War, which ended with all three countries officially becoming communist states by 1976.

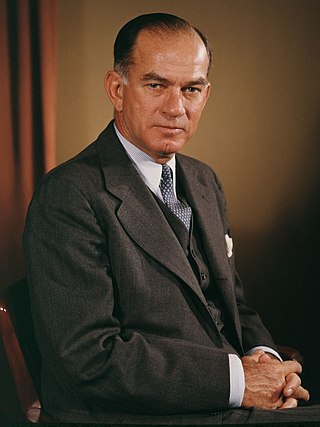

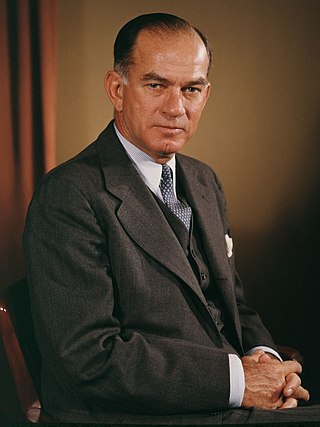

Melvin Robert Laird Jr. was an American politician, writer and statesman. He was a U.S. congressman from Wisconsin from 1953 to 1969 before serving as Secretary of Defense from 1969 to 1973 under President Richard Nixon. Laird was instrumental in forming the administration's policy of withdrawing U.S. soldiers from the Vietnam War; he coined the expression "Vietnamization," referring to the process of transferring more responsibility for combat to the South Vietnamese forces. First elected in 1952, Laird was the last surviving Representative elected to the 83rd Congress at the time of his death.

The First Indochina War was fought between France and Việt Minh, and their respective allies, from 19 December 1946 until 20 July 1954. Việt Minh was led by Võ Nguyên Giáp and Hồ Chí Minh. Most of the fighting took place in Tonkin in Northern Vietnam, although the conflict engulfed the entire country and also extended into the neighboring French Indochina protectorates of Laos and Cambodia.

James William Fulbright was an American politician, academic, and statesman who represented Arkansas in the United States Senate from 1945 until his resignation in 1974. As of 2023, Fulbright is the longest serving chairman in the history of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. He is best known for his strong multilateralist positions on international issues, opposition to American involvement in the Vietnam War, and the creation of the international fellowship program bearing his name, the Fulbright Program.

Vietnamization was a policy of the Richard Nixon administration to end U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War through a program to "expand, equip, and train South Vietnamese forces and assign to them an ever-increasing combat role, at the same time steadily reducing the number of U.S. combat troops". Brought on by the Viet Cong's Tet Offensive, the policy referred to U.S. combat troops specifically in the ground combat role, but did not reject combat by the U.S. Air Force, as well as the support to South Vietnam, consistent with the policies of U.S. foreign military assistance organizations. U.S. citizens' mistrust of their government that had begun after the offensive worsened with the release of news about U.S. soldiers massacring civilians at My Lai (1968), the invasion of Cambodia (1970), and the leaking of the Pentagon Papers (1971).

The Geneva Conference was a conference that was intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War and the First Indochina War and involved several nations. It took place in Geneva, Switzerland, from 26 April to 20 July 1954. The part of the conference on the Korean question ended without adopting any declarations or proposals and so is generally considered less relevant. The Geneva Accords that dealt with the dismantling of French Indochina proved to have long-lasting repercussions, however. The crumbling of the French colonial empire in Southeast Asia led to the formation of the states of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the State of Vietnam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, and the Kingdom of Laos. Three agreements about French Indochina, covering Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, were signed on 21 July 1954 and took effect two days later.

Jeremiah Andrew Denton Jr. was an American politician and military officer who served as a U.S. Senator representing Alabama from 1981 to 1987. He was the first Republican to be popularly elected to a Senate seat in Alabama. Denton was previously a United States Navy rear admiral and naval aviator taken captive during the Vietnam War.

Swift Vets and POWs for Truth, formerly known as the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth (SBVT), was a political group of United States Swift boat veterans and former prisoners of war of the Vietnam War, formed during the 2004 presidential election campaign for the purpose of opposing John Kerry's candidacy for the presidency. The campaign inspired the widely used political pejorative "swiftboating", to describe an unfair or untrue political attack. The group disbanded and ceased operations on May 31, 2008.

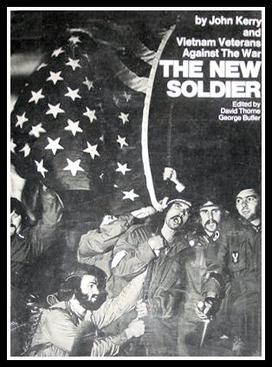

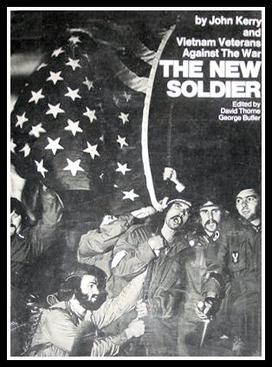

The New Soldier was published as both a hard and soft cover book in October, 1971, by Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Principally a photographic essay accompanied by text, the work was edited by David Thorne and George Butler, with a section written by John Kerry. The work includes photographs captured by many photographers across five days in April, 1971.

The McGovern–Hatfield Amendment was a proposed amendment to an appropriations bill in 1970 during the Vietnam War that, if passed, would have required the end of United States military operations in the Republic of Vietnam by December 31, 1970 and a complete withdrawal of American forces halfway through the next year. It was the most outstanding defiance of executive power regarding the war prior to 1971. The amendment was proposed by Senators George McGovern of South Dakota and Mark Hatfield of Oregon, and was known as the "amendment to end the war."

America in Vietnam is a book by Guenter Lewy about America's role in the Vietnam War. The book is highly influential although it has remained controversial even decades after its publication. Lewy contends that the US actions in Vietnam had been neither illegal nor immoral and that tales of American atrocities were greatly exaggerated in what he understands as a "veritable industry" of war crimes allegations.

The "Winter Soldier Investigation" was a media event sponsored by the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) from January 31, 1971, to February 2, 1971. It was intended to publicize war crimes and atrocities by the United States Armed Forces and their allies in the Vietnam War. The VVAW challenged the morality and conduct of the war by showing the direct relationship between military policies and war crimes in Vietnam. The three-day gathering of 109 veterans and 16 civilians took place in Detroit, Michigan. Discharged servicemen from each branch of the armed forces, as well as civilian contractors, medical personnel and academics, all gave testimony about war crimes they had committed or witnessed during the years 1963–1970.

Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) is an American tax-exempt non-profit organization and corporation founded in 1967 to oppose the United States policy and participation in the Vietnam War. VVAW says it is a national veterans' organization that campaigns for peace, justice, and the rights of all United States military veterans. It publishes a twice-yearly newsletter, The Veteran; this was earlier published more frequently as 1st Casualty (1971–1972) and then as Winter Soldier (1973–1975).

United States involvement in the Vietnam War began shortly after the end of World War II in Asia, first in an extremely limited capacity and escalating over a period of 20 years. The U.S. military presence peaked in April 1969, with 543,000 American combat troops stationed in Vietnam. By the conclusion of the United States's involvement in 1973, over 3.1 million Americans had been stationed in Vietnam.

The National Committee for a Citizens Commission of Inquiry on U.S. war crimes in Vietnam was founded in New York by Ralph Schoenman in November 1969 to document American atrocities throughout Indochina. The formation of the organization was prompted by the disclosure of the My Lai Massacre on November 12, 1969, by Seymour Hersh, writing for the New York Times. The group was the first to bring to public attention the testimony of American Vietnam War veterans who had witnessed or participated in atrocities.

The Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs was a special committee convened by the United States Senate during the George H. W. Bush administration to investigate the Vietnam War POW/MIA issue, that is, the fate of United States service personnel listed as missing in action during the Vietnam War. The committee was in existence from August 2, 1991 to January 2, 1993.

Formal relations between the United States and Vietnam were initiated in the nineteenth century under U.S. president Andrew Jackson, but relations soured after the U.S. refused to protect the Kingdom of Vietnam from French invasion. During World War II, the U.S. covertly assisted the Viet Minh in fighting Japanese forces in French Indochina, though a formal alliance was not established. After the dissolution of French Indochina in 1954, the U.S. supported the capitalist South Vietnam as opposed to Marxist-Leninist North Vietnam and fought North Vietnam directly during the Vietnam War. After American withdrawal in 1973 and the subsequent fall of South Vietnam in 1975, the U.S. applied a trade embargo and severed ties with Vietnam, mostly out of concerns relating to Vietnamese boat people and the Vietnam War POW/MIA issue. Attempts at re-establishing relations went unfulfilled for decades, until U.S. president Bill Clinton began normalizing diplomatic relations in the 1990s. In 1994, the U.S. lifted its 30-year trade embargo on Vietnam. The following year, both countries established embassies and consulates. Relations between the two countries continued to improve into the 21st century.

The Vietnam War POW/MIA issue concerns the fate of United States servicemen who were reported as missing in action (MIA) during the Vietnam War and associated theaters of operation in Southeast Asia. The term also refers to issues related to the treatment of affected family members by the governments involved in these conflicts. Following the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, 591 U.S. prisoners of war (POWs) were returned during Operation Homecoming. The United States listed about 2,500 Americans as prisoners of war or missing in action but only 1,200 Americans were reported to have been killed in action with no body recovered. Many of these were airmen who were shot down over North Vietnam or Laos. Investigations of these incidents have involved determining whether the men involved survived being shot down. If they did not survive, then the U.S. government considered efforts to recover their remains. POW/MIA activists played a role in pushing the U.S. government to improve its efforts in resolving the fates of these missing service members. Progress in doing so was slow until the mid-1980s when relations between the United States and Vietnam began to improve and more cooperative efforts were undertaken. Normalization of the U.S. relations with Vietnam in the mid-1990s was a culmination of this process.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, Pub. L. 88–408, 78 Stat. 384, enacted August 10, 1964, was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Members of the United States armed forces were held as prisoners of war (POWs) in significant numbers during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1973. Unlike U.S. service members captured in World War II and the Korean War, who were mostly enlisted troops, the overwhelming majority of Vietnam-era POWs were officers, most of them Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps airmen; a relatively small number of Army enlisted personnel were also captured, as well as one enlisted Navy seaman, Petty Officer Doug Hegdahl, who fell overboard from a naval vessel. Most U.S. prisoners were captured and held in North Vietnam by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN); a much smaller number were captured in the south and held by the Việt Cộng (VC). A handful of U.S. civilians were also held captive during the war.