Anubis, also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Ancient Egyptian religion was a complex system of polytheistic beliefs and rituals that formed an integral part of ancient Egyptian culture. It centered on the Egyptians' interactions with many deities believed to be present in, and in control of the world. Rituals such as prayer and offerings were provided to the gods to gain their favor. Formal religious practice centered on the pharaohs, the rulers of Egypt, believed to possess divine powers by virtue of their positions. They acted as intermediaries between their people and the gods, and were obligated to sustain the gods through rituals and offerings so that they could maintain Ma'at, the order of the cosmos, and repel Isfet, which was chaos. The state dedicated enormous resources to religious rituals and to the construction of temples.

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of the living. Some groups venerate their direct, familial ancestors. Certain sects and religions, in particular the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, venerate saints as intercessors with God; the latter also believes in prayer for departed souls in Purgatory. Other religious groups, however, consider veneration of the dead to be idolatry and a sin.

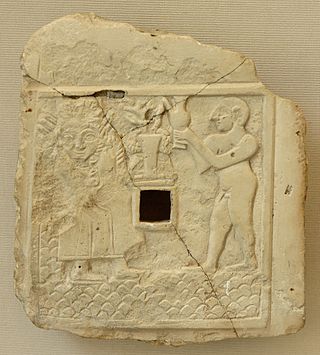

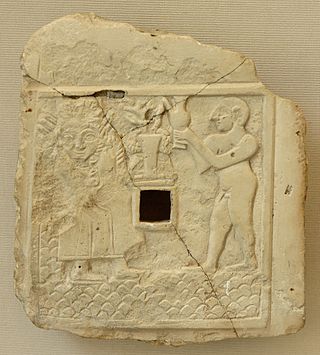

A libation is a ritual pouring of a liquid, or grains such as rice, as an offering to a deity or spirit, or in memory of the dead. It was common in many religions of antiquity and continues to be offered in cultures today.

Joss paper, also known as incense papers, are papercrafts or sheets of paper made into burnt offerings common in Chinese ancestral worship. Worship of deities in Chinese folk religion also uses a similar type of joss paper. Joss paper, as well as other papier-mâché items, are also burned or buried in various Asian funerals, "to ensure that the spirit of the deceased has sufficient means in the afterlife." In Taiwan alone, the annual revenue of temples received from burning joss paper was US$400 million as of 2014.

Cult is the care owed to deities and temples, shrines, or churches. Cult is embodied in ritual and ceremony. Its present or former presence is made concrete in temples, shrines and churches, and cult images, including votive offerings at votive sites.

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" refers to the mortal offspring of a human and a god. By the historical period, however, the word came to mean specifically a dead man, venerated and propitiated at his tomb or at a designated shrine, because his fame during life or his unusual manner of death gave him power to support and protect the living. A hero was more than human but less than a god, and various kinds of supernatural figures came to be assimilated to the class of heroes; the distinction between a hero and a god was less than certain, especially in the case of Heracles, the most prominent, but atypical hero.

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Roman funerary practices include the Ancient Romans' religious rituals concerning funerals, cremations, and burials. They were part of time-hallowed tradition, the unwritten code from which Romans derived their social norms. Elite funeral rites, especially processions and public eulogies, gave the family opportunity to publicly celebrate the life and deeds of the deceased, their ancestors, and the family's standing in the community. Sometimes the political elite gave costly public feasts, games and popular entertainments after family funerals, to honour the departed and to maintain their own public profile and reputation for generosity. The Roman gladiator games began as funeral gifts for the deceased in high status families.

The Punic religion, Carthaginian religion, or Western Phoenician religion in the western Mediterranean was a direct continuation of the Phoenician variety of the polytheistic ancient Canaanite religion. However, significant local differences developed over the centuries following the foundation of Carthage and other Punic communities elsewhere in North Africa, southern Spain, Sardinia, western Sicily, and Malta from the ninth century BC onward. After the conquest of these regions by the Roman Republic in the third and second centuries BC, Punic religious practices continued, surviving until the fourth century AD in some cases. As with most cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, Punic religion suffused their society and there was no stark distinction between religious and secular spheres. Sources on Punic religion are poor. There are no surviving literary sources and Punic religion is primarily reconstructed from inscriptions and archaeological evidence. An important sacred space in Punic religion appears to have been the large open air sanctuaries known as tophets in modern scholarship, in which urns containing the cremated bones of infants and animals were buried. There is a long-running scholarly debate about whether child sacrifice occurred at these locations, as suggested by Greco-Roman and biblical sources.

The traditional Berber religion is the ancient and native set of beliefs and deities adhered to by the Berbers of North Africa. Many ancient Amazigh beliefs were developed locally, whereas others were influenced over time through contact with others like ancient Egyptian religion, or borrowed during antiquity from the Punic religion, Judaism, Iberian mythology, and the Hellenistic religion. The most recent influence came from Islam and religion in pre-Islamic Arabia during the medieval period. Some of the ancient Amazigh beliefs still exist today subtly within the Amazigh popular culture and tradition. Syncretic influences from the traditional Amazigh religion can also be found in certain other faiths.

Death rituals were an important part of Maya religion. The Maya greatly respected death; they were taught to fear it and grieved deeply for the deceased. They also believed that certain deaths were more noble than others.

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs, tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

Chinese ancestor veneration, also called Chinese ancestor worship, is an aspect of the Chinese traditional religion which revolves around the ritual celebration of the deified ancestors and tutelary deities of people with the same surname organised into lineage societies in ancestral shrines. Ancestors, their ghosts, or spirits, and gods are considered part of "this world". They are neither supernatural nor transcendent in the sense of being beyond nature. The ancestors are humans who have become godly beings, beings who keep their individual identities. For this reason, Chinese religion is founded on veneration of ancestors. Ancestors are believed to be a means of connection to the supreme power of Tian as they are considered embodiments or reproducers of the creative order of Heaven. It is a major aspect of Han Chinese religion, but the custom has also spread to ethnic minority groups.

Ancient Greek funerary practices are attested widely in literature, the archaeological record, and in ancient Greek art. Finds associated with burials are an important source for ancient Greek culture, though Greek funerals are not as well documented as those of the ancient Romans.

Chinese funeral rituals comprise a set of traditions broadly associated with Chinese folk religion, with different rites depending on the age of the deceased, the cause of death, and the deceased's marital and social statuses. Different rituals are carried out in different parts of China, and many contemporary Chinese people carry out funerals according to various religious faiths such as Buddhism or Christianity. However, in general, the funeral ceremony itself is carried out over seven days, and mourners wear funerary dress according to their relationship to the deceased. Traditionally, white clothing is symbolic of the dead, while red is not usually worn, as it is traditionally the symbolic colour of happiness worn at Chinese weddings. The number three is significant, with many customary gestures being carried out three times.

The Nabataean religion was a form of Arab polytheism practiced in Nabataea, an ancient Arab nation which was well settled by the third century BCE and lasted until the Roman annexation in 106 CE. The Nabateans were polytheistic and worshipped a wide variety of local gods as well as Baalshamin, Isis, and Greco-Roman gods such as Tyche and Dionysus. They worshipped their gods at temples, high places, and betyls. They were mostly aniconic and preferred to decorate their sacred places with geometric designs. Much knowledge of the Nabataeans’ grave goods has been lost due to extensive looting throughout history. They made sacrifices to their gods, performed other rituals and believed in an afterlife.

The Samnites were an ancient Italic people who lived in modern south-central Italy, placing them between the Latins to the north and the Greek settlements to the south. Consequently, the Samnites had anthropomorphic deities shared with both Rome and Greece, especially after their conquest of Campania at the end of the fourth century BCE. There is additional evidence that suggests the Samnites also believed in spirits called numina. Numina are believed to have been kinless, animistic spirits that could take human form to walk amongst the living. To the Samnites, having good relations with these spirits was of the utmost importance. To honor these deities, the Samnites would sacrifice either living things or make votive offerings.