Related Research Articles

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms in the sea. Given that in biology many phyla, families and genera have some species that live in the sea and others that live on land, marine biology classifies species based on the environment rather than on taxonomy.

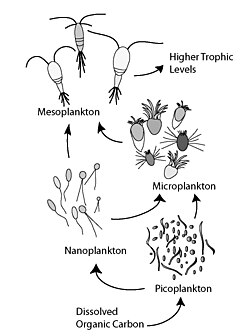

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water that are unable to propel themselves against a current. The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucial source of food to many small and large aquatic organisms, such as bivalves, fish and whales.

An aerobic organism or aerobe is an organism that can survive and grow in an oxygenated environment. In contrast, an anaerobic organism (anaerobe) is any organism that does not require oxygen for growth. Some anaerobes react negatively or even die if oxygen is present. The ability to exhibit aerobic respiration may yield benefits to the aerobic organism, as aerobic respiration yields more energy than anaerobic respiration. In July 2020, marine biologists reported that aerobic microorganisms (mainly), in "quasi-suspended animation", were found in organically-poor sediments, up to 101.5 million years old, 250 feet below the seafloor in the South Pacific Gyre (SPG), and could be the longest-living life forms ever found.

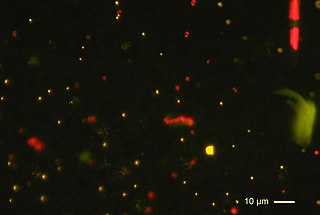

Prochlorococcus is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation. These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosynthetic organism on Earth. Prochlorococcus microbes are among the major primary producers in the ocean, responsible for a large percentage of the photosynthetic production of oxygen. Prochlorococcus strains, called ecotypes, have physiological differences enabling them to exploit different ecological niches. Analysis of the genome sequences of Prochlorococcus strains show that 1,273 genes are common to all strains, and the average genome size is about 2,000 genes. In contrast, eukaryotic algae have over 10,000 genes.

Microbial ecology is the ecology of microorganisms: their relationship with one another and with their environment. It concerns the three major domains of life—Eukaryota, Archaea, and Bacteria—as well as viruses.

Photosynthetic picoplankton or picophytoplankton is the fraction of the phytoplankton performing photosynthesis composed of cells between 0.2 and 2 µm in size (picoplankton). It is especially important in the central oligotrophic regions of the world oceans that have very low concentration of nutrients.

Sallie Watson "Penny" Chisholm is an American biological oceanographer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She is an expert in the ecology and evolution of ocean microbes. Her research focuses particularly on the most abundant marine phytoplankton, Prochlorococcus, that she discovered in the 1980s with Rob Olson and other collaborators. She has a TED talk about their discovery and importance called "The tiny creature that secretly powers the planet".

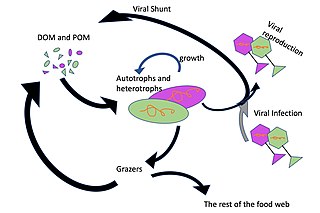

The microbial loop describes a trophic pathway where, in aquatic systems, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is returned to higher trophic levels via its incorporation into bacterial biomass, and then coupled with the classic food chain formed by phytoplankton-zooplankton-nekton. In soil systems, the microbial loop refers to soil carbon. The term microbial loop was coined by Farooq Azam, Tom Fenchel et al. in 1983 to include the role played by bacteria in the carbon and nutrient cycles of the marine environment.

Colleen Marie Cavanaugh is an American academic microbiologist best known for her studies of hydrothermal vent ecosystems. As of 2002, she is the Edward C. Jeffrey Professor of Biology in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University and is affiliated with the Marine Biological Laboratory and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Cavanaugh was the first to propose that the deep-sea giant tube worm, Riftia pachyptila, obtains its food from bacteria living within its cells, an insight which she had as a graduate student at Harvard. Significantly, she made the connection that these chemoautotrophic bacteria were able to play this role through their use of chemosynthesis, the biological oxidation of inorganic compounds to synthesize organic matter from very simple carbon-containing molecules, thus allowing organisms such as the bacteria to exist in deep ocean without sunlight.

In the deep ocean, marine snow is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to the aphotic zone below, which is referred to as the biological pump. Export production is the amount of organic matter produced in the ocean by primary production that is not recycled (remineralised) before it sinks into the aphotic zone. Because of the role of export production in the ocean's biological pump, it is typically measured in units of carbon. The term was first coined by the explorer William Beebe as he observed it from his bathysphere. As the origin of marine snow lies in activities within the productive photic zone, the prevalence of marine snow changes with seasonal fluctuations in photosynthetic activity and ocean currents. Marine snow can be an important food source for organisms living in the aphotic zone, particularly for organisms which live very deep in the water column.

Bacterioplankton refers to the bacterial component of the plankton that drifts in the water column. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word πλανκτος, meaning "wanderer" or "drifter", and bacterium, a Latin term coined in the 19th century by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg. They are found in both seawater and freshwater.

Antje Boetius is a German marine biologist. She is a professor of geomicrobiology at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, University of Bremen. Boetius received the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize in March 2009 for her study of sea bed microorganisms that affect the global climate. She is also the director of Germany's polar research hub, the Alfred Wegener Institute.

Genomic streamlining is a theory in evolutionary biology and microbial ecology that suggests that there is a reproductive benefit to prokaryotes having a smaller genome size with less non-coding DNA and fewer non-essential genes. There is a lot of variation in prokaryotic genome size, with the smallest free-living cell's genome being roughly ten times smaller than the largest prokaryote. Two of the bacterial taxa with the smallest genomes are Prochlorococcus and Pelagibacter ubique, both highly abundant marine bacteria commonly found in oligotrophic regions. Similar reduced genomes have been found in uncultured marine bacteria, suggesting that genomic streamlining is a common feature of bacterioplankton. This theory is typically used with reference to free-living organisms in oligotrophic environments.

An oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) is characterized as an oxygen-deficient layer in the world oceans. Typically found between 200m to 1500m deep below regions of high productivity, such as the western coasts of continents. OMZs can be seasonal following the spring-summer upwelling season. Upwelling of nutrient-rich water leads to high productivity and labile organic matter, that is respired by heterotrophs as it sinks down the water column. High respiration rates deplete the oxygen in the water column to concentrations of 2 mg/L or less forming the OMZ. OMZs are expanding, with increasing ocean deoxygenation. Under these oxygen-starved conditions, energy is diverted from higher trophic levels to microbial communities that have evolved to use other biogeochemical species instead of oxygen, these species include Nitrate, Nitrite, Sulphate etc. Several Bacteria and Archea have adapted to live in these environments by using these alternate chemical species and thrive. The most abundant phyla in OMZs are Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, and Planctomycetota.

Lisa A. Levin is a Distinguished Professor of biological oceanography and marine ecology at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. She holds the Elizabeth Hamman and Morgan Dene Oliver Chair in Marine Biodiversity and Conservation Science. She studies coastal and deep-sea ecosystems and is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The viral shunt is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter (POM) from migrating up trophic levels by recycling them into dissolved organic matter (DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. The DOM recycled by the viral shunt pathway is comparable to the amount generated by the other main sources of marine DOM.

Bess Ward is an American oceanographer, biogeochemist, microbiologist, and William J. Sinclair Professor of Geosciences at Princeton University.

Barbara Mary Hickey is an Emeritus Professor of Oceanography at the University of Washington. Her research involves field measurements and computational models to understand coastal processes. She is a Fellow of the American Geophysical Union.

Kimberly B. Ritchie is an American marine biologist. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Natural Sciences at the University of South Carolina Beaufort. Her research is focused on marine microbiology and how microbes affect animal health in hosts such as corals and sharks.

Debbie Lindell is the Dresner Chair in life sciences and medicine at Technion - Israel Institute of Technology. She is known for her work on the interactions between viruses and their hosts in marine environments.

References

- ↑ Hickey, Hannah (May 1, 2019). "Arsenic-breathing life discovered in the tropical Pacific Ocean". UW News. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- 1 2 "Microbes''blueprints' promise insights into oceans, more". MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- 1 2 3 "Gabrielle Rocap – The Rocap Lab" . Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ↑ "Gabrielle Rocap" . Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ↑ "Gabrielle Rocap | BCO-DMO". www.bco-dmo.org. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- 1 2 "Biologists Find Arsenic-Breathing Microbes in Oxygen-Poor Regions of Pacific Ocean | Sci-News.com". Breaking Science News | Sci-News.com. May 9, 2019. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ↑ "Microbes in the Pacific Ocean survive on arsenic". Futurity. 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2022-03-07.