A microlith is a small stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 35,000 to 3,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. The microliths were used in spear points and arrowheads.

Marine archeology in the Gulf of Khambhat - earlier known as Gulf of Cambay - centers around controversial findings made in December 2000 by the National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT) under the Gulf of Khambhat, a bay on the Arabian Sea on the west coast of India. The structures and artifacts discovered by NIOT are the subject of contention. The major disputes surrounding the Gulf of Khambhat Cultural Complex (GKCC) are claims about the existence of submerged city-like structures, the difficulty associating dated artifacts with the site itself, and disputes about whether stone artifacts recovered at the site are actually geofacts or artifacts. One major complaint is that artifacts at the site were recovered by dredging, instead of being recovered during a controlled archeological excavation. This leads archeologists to claim that these artifacts cannot be definitively tied to the site. Because of this problem, prominent archeologists reject a piece of wood that was recovered by dredging and dated to 7500 BC as having any significance in dating the site. The surveys were followed up in the following years and two palaeo channels of old rivers were discovered in the middle of the Khambhat area under 20–40 m (66–131 ft) water depths, at a distance of about 20 km (12 mi) from the present day coast.

In archaeology, a hammerstone is a hard cobble used to strike off lithic flakes from a lump of tool stone during the process of lithic reduction. The hammerstone is a rather universal stone tool which appeared early in most regions of the world including Europe, India and North America. This technology was of major importance to prehistoric cultures before the age of metalworking.

In archaeology, in particular of the Stone Age, lithic reduction is the process of fashioning stones or rocks from their natural state into tools or weapons by removing some parts. It has been intensely studied and many archaeological industries are identified almost entirely by the lithic analysis of the precise style of their tools and the chaîne opératoire of the reduction techniques they used.

In archaeology, lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level, lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact's Morphology (archaeology), the measurement of various physical attributes, and examining other visible features.

An artifact or artefact is a general term for an item made or given shape by humans, such as a tool or a work of art, especially an object of archaeological interest. In archaeology, the word has become a term of particular nuance and is defined as an object recovered by archaeological endeavor, which may be a cultural artifact having cultural interest.

In archaeology, a denticulate tool is a stone tool containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes, much like the toothed edge of a saw. Such tools have been used as saws for woodworking, processing meat and hides, craft activities and for agricultural purposes. Denticulate tools were used by many different groups worldwide and have been found at a number of notable archaeological sites. They can be made from a number of different lithic materials, but a large number of denticulate tools are made from flint.

In the archaeology of the Stone Age, an industry or technocomplex is a typological classification of stone tools.

The Levallois technique is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was used by the Neanderthals in Europe and by modern humans in other regions such as the Levant.

The Calico Early Man Site is an archaeological site in an ancient Pleistocene lake located near Barstow in San Bernardino County in the central Mojave Desert of Southern California. This site is on and in late middle-Pleistocene fanglomerates known variously as the Calico Hills, the Yermo Hills, or the Yermo formation. Holocene evidence includes petroglyphs and trail segments that are probably related to outcrops of local high-quality siliceous rock.

In archaeology, debitage is all the material produced during the process of lithic reduction – the production of stone tools and weapons by knapping stone. This assemblage may include the different kinds of lithic flakes and lithic blades, but most often refers to the shatter and production debris, and production rejects.

Wolf Cave is a crack in the Pyhävuori mountain in Kristinestad, near the Karijoki municipality in Finland. The upper part of the crack has been packed with soil, forming a cave. In 1996, some objects were found in the cave that brought about speculations that it could have been inhabited in the Paleolithic, between 120,000 and 130,000 years ago. These objects, if authentic, would be the only known Neanderthal artifacts in the Nordic countries.

The Soanian culture is a prehistoric technological culture from the Siwalik Hills in the Indian subcontinent. It is named after the Soan Valley in Pakistan. Soanian sites are found along the Siwalik region in present-day India, Nepal and Pakistan. The Soanian culture has been approximated to have taken place during the Middle Pleistocene period or the mid-Holocene epoch (Northgrippian). Debates still goes on today regarding the exact period occupied by the culture due to artefacts often being found in non-datable surface context. This culture was first discovered and named by the anthropology and archaeology team led by Helmut De Terra and Thomas Thomson Paterson. Soanian artifacts were manufactured on quartzite pebbles, cobbles, and occasionally on boulders, all derived from various fluvial sources on the Siwalik landscape. Soanian assemblages generally comprise varieties of choppers, discoids, scrapers, cores, and numerous flake type tools, all occurring in varying typo-technological frequencies at different sites.

Howieson's Poort Shelter is a small rock shelter in South Africa containing the archaeological site from which the Howiesons Poort period in the Middle Stone Age gets its name. This period lasted around 5,000 years, between roughly 65,800 BP and 59,500 BP. This period is important as it, together with the Stillbay period 7,000 years earlier, provides the first evidence of human symbolism and technological skills that were later to appear in the Upper Paleolithic.

Franktown Cave is located 25 miles (40 km) south of Denver, Colorado on the north edge of the Palmer Divide. It is the largest rock shelter documented on the Palmer Divide, which contains artifacts from many prehistoric cultures. Prehistoric hunter-gatherers occupied Franktown Cave intermittently for 8,000 years beginning about 6400 BC The site held remarkable lithic and ceramic artifacts, but it is better known for its perishable artifacts, including animal hides, wood, fiber and corn. Material goods were produced for their comfort, task-simplification and religious celebration. There is evidence of the site being a campsite or dwelling as recently as AD 1725.

A weathering rind is a discolored, chemically altered, outer zone or layer of a discrete rock fragment formed by the processes of weathering. The inner boundary of a weathering rind approximately parallels the outer surface of the rock fragment in which it has developed. Rock fragments with weathering rinds normally are discrete clasts, ranging in size from pebbles to cobbles or boulders. They typically occur either lying on the surface of the ground or buried within sediments such as alluvium, colluvium, or glacial till. A weathering rind represents the alteration of the outer portion of a rock by exposure to air or near surface groundwater over a period of time. Typically, a weathering rind may be enriched with either iron or manganese, and silica, and oxidized to a yellowish red to reddish color. Often a weathering rind exhibits multiple bands of differing colors.

The Hadži-Prodan's Cave is an archaeological site of the Paleolithic period and a national natural monument, located in the village Raščići around 7 km (4.3 mi) from Ivanjica in western central Serbia. The rather narrow and high entrance with at an altitude of 630 m (2,070 ft) above sea level sits about 40 m (130 ft) above the Rašćanska river valley bed and is oriented towards the south. The 345 m (1,132 ft) long cave was formed during the Late Cretaceous in "thick-bedded to massive" Senonian limestone. Prehistoric pottery shards and Pleistocene faunal fossils had already been collected by Zoran Vučićević from Ivanjica. Animal fossils especially Cave bear and Iron Age artifact discoveries during an unrelated areal survey were reportedly made at the cave entrance and in the main cavern. The site is named in honor of Hadži-Prodan, a 19th century Serbian revolutionary.

Melkhoutboom Cave is an archaeological site dating to the Later Stone Age, located in the Zuurberg Mountains, Cape Folded Mountain Belt, in the Addo Elephant National Park, Sarah Baartman District Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa.

Obłazowa Cave is a cave situated in the nature reserve of Przełom Białki at Nowa Biała near Krempachy, Gmina Nowy Targ in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, southern Poland. The cave has a 9 m long chamber to which a short corridor leads. It is one of the most important Paleolithic sites in Poland.

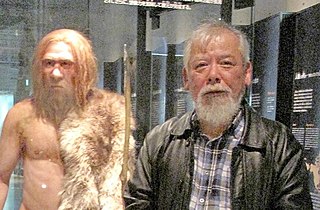

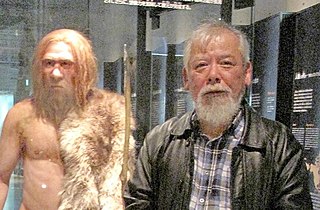

Katsuhiko Ohnuma is a Japanese prehistorian and lithic expert. He was director of the Institute for Cultural Studies of Ancient Iraq, Kokushikan University.