The Batavi were an ancient Germanic tribe that lived around the modern Dutch Rhine delta in the area that the Romans called Batavia, from the second half of the first century BC to the third century AD. The name is also applied to several military units employed by the Romans that were originally raised among the Batavi. The tribal name, probably a derivation from batawjō, refers to the region's fertility, today known as the fruitbasket of the Netherlands.

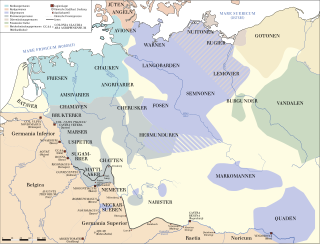

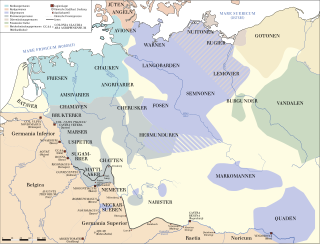

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Northwestern and Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and early medieval Germanic languages and are thus equated at least approximately with Germanic-speaking peoples, although different academic disciplines have their own definitions of what makes someone or something "Germanic". The Romans named the area belonging to North-Central Europe in which Germanic peoples lived Germania, stretching east to west between the Vistula and Rhine rivers and north to south from southern Scandinavia to the upper Danube. In discussions of the Roman period, the Germanic peoples are sometimes referred to as Germani or ancient Germans, although many scholars consider the second term problematic since it suggests identity with present-day Germans. The very concept of "Germanic peoples" has become the subject of controversy among contemporary scholars. Some scholars call for its total abandonment as a modern construct since lumping "Germanic peoples" together implies a common group identity for which there is little evidence. Other scholars have defended the term's continued use and argue that a common Germanic language allows one to speak of "Germanic peoples", regardless of whether these ancient and medieval peoples saw themselves as having a common identity. While several historians and archaeologists continue to use the term "Germanic peoples" to refer to historical people groups from the 1st to 4th centuries CE, the term is no longer used by most historians and archaeologists for the period around the Fall of the Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, described as the Varian Disaster by Roman historians, was a major battle between Germanic tribes and the Roman Empire that took place somewhere near modern Kalkriese from September 8–11, 9 AD, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed three Roman legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus and their auxiliaries. The alliance was led by Arminius, a Germanic officer of Varus's auxilia. Arminius had acquired Roman citizenship and had received a Roman military education, which enabled him to deceive the Roman commander methodically and anticipate the Roman army's tactical responses.

Arminius was a chieftain of the Germanic Cherusci tribe who is best known for commanding an alliance of Germanic tribes at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9, in which three Roman legions under the command of general and governor Publius Quinctilius Varus were destroyed. His victory at Teutoburg Forest precipitated the Roman Empire's permanent strategic withdrawal from Germania Magna, and modern historians regard it as one of Rome's greatest defeats. As it prevented the Romanization of Germanic peoples east of the Rhine, it has also been considered one of the most decisive battles in history and a turning point in human history.

Germania, also called Magna Germania, Germania Libera, or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a historical region in north-central Europe during the Roman era, which was associated by Roman authors with the Germanic people. The region stretched roughly from the Middle and Lower Rhine in the west to the Vistula in the east. It also extended at some point as far south as the Upper and Middle Danube and Pannonia, and to the known parts of southern Scandinavia in the north. Archaeologically, these people correspond roughly to the Roman Iron Age of those regions. While dominated by Germanic people, Magna Germania was also inhabited by a few other Indo-European people.

The Revolt of the Batavi took place in the Roman province of Germania Inferior between AD 69 and 70. It was an uprising against the Roman Empire started by the Batavi, a small but militarily powerful Germanic tribe that inhabited Batavia, on the delta of the river Rhine. They were soon joined by the Celtic tribes from Gallia Belgica and some Germanic tribes.

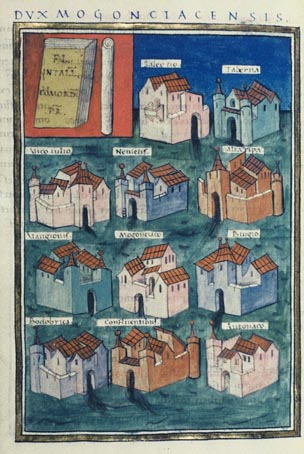

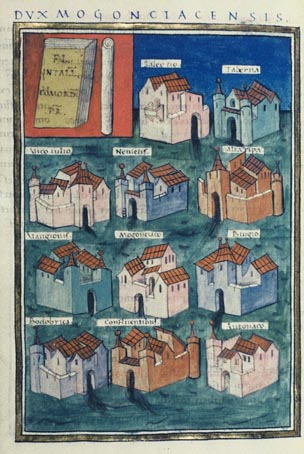

Germania Inferior was a Roman province from AD 85 until the province was renamed Germania Secunda in the 4th century AD, on the west bank of the Rhine bordering the North Sea. The capital of the province was Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium.

This is a chronology of warfare between the Romans and various Germanic peoples. The nature of these wars varied through time between Roman conquest, Germanic uprisings, later Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire that started in the late second century BC, and more. The series of conflicts was one factor which led to the ultimate downfall of the Western Roman Empire in particular and ancient Rome in general in 476.

The Vangiones appear first in history as an ancient Germanic tribe of unknown provenance. They threw in their lot with Ariovistus in his bid of 58 BC to invade Gaul through the Doubs river valley and lost to Julius Caesar in a battle probably near Belfort. After some Celts evacuated the region in fear of the Suebi, the Vangiones, who had made a Roman peace, were allowed to settle among the Mediomatrici in northern Alsace.. They gradually assumed control of the Celtic city of Burbetomagus, later Worms.

The Angrivarii were a Germanic people of the early Roman Empire, who lived in what is now northwest Germany near the middle of the Weser river. They were mentioned by the Roman authors Tacitus and Ptolemy.

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain, roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

Roman Iron Age weapon deposits are intentional burial of weapons stashes from the Roman Iron Age of Scandinavia. The weapon deposits were intended for either sacrifice or burial and forms part of other Iron Age votive offerings from the period of bog deposits in Scandinavia. Almost all Scandinavian Iron Age bog deposits have been found in Denmark and southern Sweden, including Gotland.

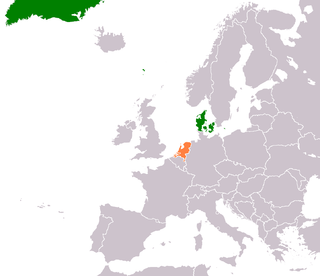

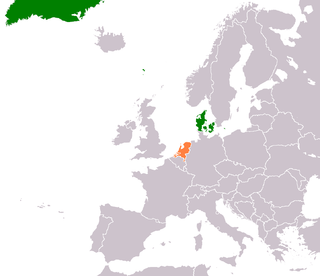

Denmark–Netherlands relations are the bilateral relations between Denmark and the Netherlands. The Netherlands has an embassy in Copenhagen and Denmark has an embassy in The Hague. Both countries are full members of the Council of Europe, the European Union and NATO. Princess Beatrix is a Dame of the Order of the Elephant since 29 October 1975. On 31 January 1998, King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands also received the Order of the Elephant.

For around 450 years, from around 55 BC to around 410 AD, the southern part of the Netherlands was integrated into the Roman Empire. During this time the Romans in the Netherlands had an enormous influence on the lives and culture of the people who lived in the Netherlands at the time and (indirectly) on the generations that followed.

The Baetasii were a Germanic tribal grouping within the Roman province of Germania Inferior, which later became Germania Secunda. Their exact location is still unknown, although two proposals are, first, that it might be the source of the name of the Belgian village of Geetbets, and second, that it might be further east, nearer to the Sunuci with whom they interacted in the Batavian revolt, and to the Cugerni who lived at Xanten. The area of Gennep, Goch and Geldern has been proposed for example.

The Germani cisrhenani, or "Left bank Germani", were a group of Germanic peoples who lived west of the Lower Rhine at the time of the Gallic Wars in the mid-1st century BC.

In many areas of Scandinavia, a wide variety of items were deposited in lakes and bogs from the Mesolithic period through to the Middle Ages. Such items include earthenware, decorative metalwork, weapons, and human corpses, known as bog bodies. As Kaul noted, "we cannot get away from the fact that the depositions in the bogs were connected with the ritual/religious sphere."

The Roman campaigns in Germania were a series of conflicts between the Germanic tribes and the Roman Empire. Tensions between the Germanic tribes and the Romans began as early as 17/16 BC with the Clades Lolliana, where the 5th Legion under Marcus Lollius was defeated by the tribes Sicambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri. Roman Emperor Augustus responded by rapidly developing military infrastructure across Gaul. His general, Nero Claudius Drusus, began building forts along the Rhine in 13 BC and launched a retaliatory campaign across the Rhine in 12 BC.

Gevninge is a village, with a population of 1,652, in Lejre Municipality on the island of Zealand in Denmark. Its old section is located alongside a small river, Lejre Å, approximately 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from its mouth at Roskilde Fjord.

The Hellvi helmet eyebrow is a decorative eyebrow from a Vendel Period helmet. It comprises two fragments; the arch is made of iron decorated with strips of silver, and terminates in a bronze animal head that was cast on. The eyebrow was donated to the Statens historiska museum in November 1880 along with several other objects, all said to be from a grave find in Gotland, Sweden.