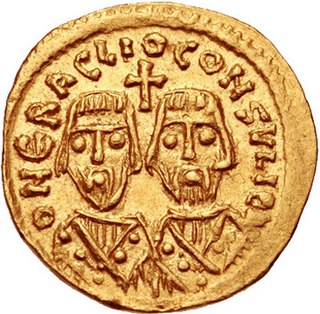

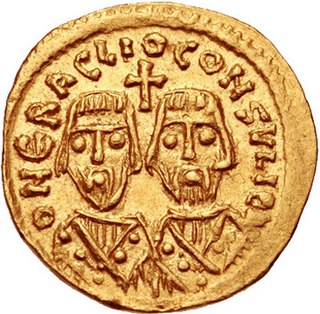

Heraclius was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas.

Monothelitism, or monotheletism is a theological doctrine in Christianity that holds Christ as having only one will. The doctrine is thus contrary to dyothelitism, a Christological doctrine that holds Christ as having two wills. Historically, monothelitism was closely related to monoenergism, a theological doctrine that holds Jesus Christ as having only one energy. Both doctrines were at the center of Christological disputes during the 7th century.

The themes or thémata were the main military and administrative divisions of the middle Byzantine Empire. They were established in the mid-7th century in the aftermath of the Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe and Muslim conquests of parts of Byzantine territory, and replaced the earlier provincial system established by Diocletian and Constantine the Great. In their origin, the first themes were created from the areas of encampment of the field armies of the East Roman army, and their names corresponded to the military units that had existed in those areas. The theme system reached its apogee in the 9th and 10th centuries, as older themes were split up and the conquest of territory resulted in the creation of new ones. The original theme system underwent significant changes in the 11th and 12th centuries, but the term remained in use as a provincial and financial circumscription until the very end of the Empire.

John I Tzimiskes was the senior Byzantine emperor from 969 to 976. An intuitive and successful general who married into the influential Skleros family, he strengthened and expanded the Byzantine Empire to include Thrace and Syria by warring with the Rus under Sviatoslav I and the Fatimids respectively.

Constans II, nicknamed "the Bearded", was the Byzantine emperor from 641 to 668. Constans was the last attested emperor to serve as consul, in 642, although the office continued to exist until the reign of Leo VI the Wise. His religious policy saw him steering a middle line in disputes between the Orthodoxy and Monothelitism by refusing to persecute either and prohibited discussion of the natures of Jesus Christ under the Type of Constans in 648. His reign coincided with Muslim invasions under, Umar, Uthman, and Mu'awiya I in the late 640s to 660s. Constans was the first emperor to visit Rome since the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, and the last one to visit Rome while it was still held by the Empire.

Monoenergism was a notion in early medieval Christian theology, representing the belief that Christ had only one "energy" (energeia). The teaching of one energy was propagated during the first half of the seventh century by Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople. Opposition to dyoenergism, its counterpart, would persist until Dyoenergism was espoused as Orthodoxy at the Sixth Ecumenical Council and monoenergism was rejected as heresy.

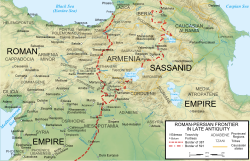

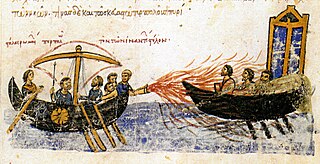

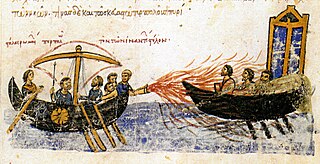

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a series of wars between a number of Muslim Arab dynasties and the Byzantine Empire from the 7th to the 11th century. Conflict started during the initial Muslim conquests, under the expansionist Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs, in the 7th century and continued by their successors until the mid-11th century.

The Ecthesis is a letter published in 638 CE by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius which defined monotheletism as the official imperial form of Christianity.

Heraclius the Elder was a Byzantine general and the father of Byzantine emperor Heraclius. Generally considered to be of Armenian origin, Heraclius the Elder distinguished himself in the war against the Sassanid Persians in the 580s. As a subordinate general, Heraclius served under the command of Philippicus during the Battle of Solachon and possibly served under Comentiolus during the Battle of Sisarbanon. Circa 595, Heraclius the Elder is mentioned as a magister militum per Armeniam sent by Emperor Maurice to quell an Armenian rebellion led by Samuel Vahewuni and Atat Khorkhoruni. Circa 600, he was appointed as the Exarch of Africa and in 608, he rebelled with his son against the usurper Phocas. Using North Africa as a base, the younger Heraclius managed to overthrow Phocas, beginning the Heraclian dynasty, which would rule Byzantium for a century. Heraclius the Elder died soon after receiving news of his son's accession to the Byzantine throne.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the dynasty of Heraclius between 610 and 711. The Heraclians presided over a period of cataclysmic events that were a watershed in the history of the Empire and the world. Heraclius, the founder of his dynasty, was of Armenian and Cappadocian (Greek) origin. At the beginning of the dynasty, the Empire's culture was still essentially Ancient Roman, dominating the Mediterranean and harbouring a prosperous Late Antique urban civilization. This world was shattered by successive invasions, which resulted in extensive territorial losses, financial collapse and plagues that depopulated the cities, while religious controversies and rebellions further weakened the Empire.

The Byzantine Empireunder the Macedonian dynasty underwent a revival during the late 9th, 10th, and early 11th centuries. Under the Macedonian emperors, the empire gained control over the Adriatic Sea, Southern Italy, and all of the territory of the Tsar Samuil of Bulgaria. The Macedonian dynasty was characterised by a cultural revival in spheres such as philosophy and the arts, and has been dubbed the "Golden Age" of Byzantium.

Between 780–1180, the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid & Fatimid caliphates in the regions of Iraq, Palestine, Syria, Anatolia and Southern Italy fought a series of wars for supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean. After a period of indecisive and slow border warfare, a string of almost unbroken Byzantine victories in the late 10th and early 11th centuries allowed three Byzantine Emperors, namely Nikephoros II Phokas, John I Tzimiskes and finally Basil II to recapture territory lost to the Muslim conquests in the 7th century Arab–Byzantine wars under the failing Heraclian Dynasty.

Gregory the Patrician was a Byzantine Exarch of Africa. A relative of the ruling Heraclian dynasty, Gregory was fiercely pro-Chalcedonian and led a rebellion in 646 against Emperor Constans II over the latter's support for Monothelism. Soon after declaring himself emperor, he faced an Arab invasion in 647. He confronted the invaders but was decisively defeated and killed at Sufetula. Africa returned to imperial allegiance after his death and the Arabs' withdrawal, but the foundations of Byzantine rule there had been fatally undermined.

Oriental Orthodoxy is the communion of Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils—the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus. They reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon. Hence, these Churches are also called Old Oriental Churches or Non-Chalcedonian Churches.

This history of the Byzantine Empire covers the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from late antiquity until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD. Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the transitional period during which the Roman Empire's east and west divided. In 285, the emperor Diocletian partitioned the Roman Empire's administration into eastern and western halves. Between 324 and 330, Constantine I transferred the main capital from Rome to Byzantium, later known as Constantinople and Nova Roma. Under Theodosius I, Christianity became the Empire's official state religion and others such as Roman polytheism were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius, the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin. Although the Roman state continued, some historians choose to distinguish the Byzantine Empire from the earlier Roman Empire due to the imperial seat moving from Rome to Byzantium, the Empire’s integration of Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin.

From c. 970 until 1018, a series of conflicts between the Bulgarian Empire and the Byzantine Empire led to the gradual reconquest of Bulgaria by the Byzantines, who thus re-established their control over the entire Balkan peninsula for the first time since the 7th-century Slavic invasions. The struggle began with the incorporation of eastern Bulgaria after the Russo-Byzantine War (970–971). Bulgarian resistance was led by the Cometopuli brothers, who – based in the unconquered western regions of the Bulgarian Empire – led it until its fall under Byzantine rule in 1018.

Byzantine Anatolia refers to the peninsula of Anatolia during the rule of the Byzantine Empire. Anatolia was of vital importance to the empire following the Muslim invasion of Syria and Egypt during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in the years 634–645 AD. Over the next two hundred and fifty years, the region suffered constant raids by Arab Muslim forces raiding mainly from the cities of Antioch, Tarsus, and Aleppo near the Anatolian borders. However, the Byzantine Empire maintained control over the Anatolian peninsula until the High Middle Ages, when imperial authority in the area began to collapse.

A reason for the longevity of the Byzantine Empire is how they managed their foreign relations. Armed combat and later its navy were the primary methods with the evolved traditions of the Roman Empire, however Byzantine diplomacy which eventuated with their many treaties was used extensively as well.