The Hurro-Urartian languages are an extinct language family of the Ancient Near East, comprising only two known languages: Hurrian and Urartian.

Hayk, also known as Hayk Nahapet, is the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation. His story is told in the History of Armenia attributed to the Armenian historian Moses of Chorene and in the Primary History traditionally attributed to Sebeos. Fragments of the legend of Hayk are also preserved in the works of other authors, as well as in Armenian folk tradition.

The Mushki were an Iron Age people of Anatolia who appear in sources from Assyria but not from the Hittites. Several authors have connected them with the Moschoi (Μόσχοι) of Greek sources and the Georgian tribe of the Meskhi. Josephus Flavius identified the Moschoi with the Biblical Meshech. Two different groups are called Muški in Assyrian sources, one from the 12th to the 9th centuries BC near the confluence of the Arsanias and the Euphrates and the other from the 8th to the 7th centuries BC in Cappadocia and Cilicia. Assyrian sources clearly identify the Western Mushki with the Phrygians, but later Greek sources then distinguish between the Phrygians and the Moschoi.

Diauehi (Georgian დიაოხი, Urartian Diauehi, Greek Taochoi, Armenian Tayk, possibly Assyrian Daiaeni) was a tribal union located in northeastern Anatolia, that was recorded in Assyrian and Urartian sources during the Iron Age. It is usually (though not always) identified with the earlier Daiaeni(Dayaeni), attested in the Yonjalu inscription of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I's third year (1118 BC) and in later records by Shalmaneser III (845 BC). While it is unknown what language(s) they spoke, they may have been speakers of a Kartvelian, Armenian, or Hurrian language.

Armenian mythology originated in ancient Indo-European traditions, specifically Proto-Armenian, and gradually incorporated Hurro-Urartian, Mesopotamian, Iranian, and Greek beliefs and deities.

The Trialeti–Vanadzor culture, previously known as the Trialeti–Kirovakan culture, is named after the Trialeti region of Georgia and the city of Vanadzor, Armenia. It is attributed to the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BCE. The Trialeti–Vanadzor culture emerged in the areas of the preceding Kura–Araxes culture. Some scholars speculate that it was an Indo-European culture. It developed into the Lchashen–Metsamor culture. It may have also given rise to the Hayasa-Azzi confederation mentioned in Hittite texts, and the Mushki mentioned by the Assyrians.

Hayasa-Azzi or Azzi-Hayasa was a Late Bronze Age confederation in the Armenian Highlands and/or Pontic region of Asia Minor. The Hayasa-Azzi confederation was in conflict with the Hittite Empire in the 14th century BC, leading up to the collapse of Hatti around 1190 BC. It has long been thought that Hayasa-Azzi may have played a significant role in the ethnogenesis of Armenians.

The origin of the Armenians is a topic concerned with the emergence of the Armenian people and the country called Armenia. The earliest universally accepted reference to the people and the country dates back to the 6th century BC Behistun Inscription, followed by several Greek fragments and books. The earliest known reference to a geopolitical entity where Armenians originated from is dated to the 13th century BC as Uruatri in Old Assyrian. Historians and Armenologists have speculated about the earlier origin of the Armenian people, but no consensus has been achieved as of yet. Genetic studies show that Armenian people are indigenous to historical Armenia, showing little to no signs of admixture since around the 13th century BC.

The name Armenia entered English via Latin, from Ancient Greek Ἀρμενία.

Proto-Armenian is the earlier, unattested stage of the Armenian language which has been reconstructed by linguists. As Armenian is the only known language of its branch of the Indo-European languages, the comparative method cannot be used to reconstruct its earlier stages. Instead, a combination of internal and external reconstruction, by reconstructions of Proto-Indo-European and other branches, has allowed linguists to piece together the earlier history of Armenian.

Shubria or Shupria was a kingdom in the southern Armenian highlands, known from Assyrian sources in the first half of the 1st millennium BC. It was located north of the upper Tigris River and to the southwest of Lake Van, extending eastwards to the frontiers of Urartu. It appears in the 1st millennium BC as an independent kingdom, succeeding the people earlier called Shubaru in Assyrian sources in the later centuries of the 2nd millennium BC. It was located between the powerful states of Assyria and Urartu and came into conflict with both. It was conquered by Assyria in 673–672 BC but likely regained its independence towards the end of the 7th century BC with the collapse of Assyrian power.

Arzashkun or Arṣashkun was the capital of the early kingdom of Urartu in the 9th century BC, before Sarduri I moved it to Tushpa in 832 BC. Arzashkun had double walls and towers, but was captured by Shalmaneser III in the 850s BC.

Prehistoric Armenia refers to the history of the region that would eventually be known as Armenia, covering the period of the earliest known human presence in the Armenian Highlands from the Lower Paleolithic more than 1 million years ago until the Iron Age and the emergence of Urartu in the 9th century BC, the end of which in the 6th century BC marks the beginning of Ancient Armenia.

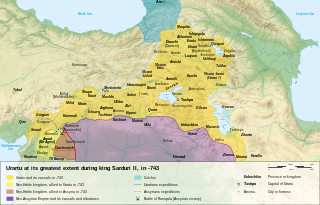

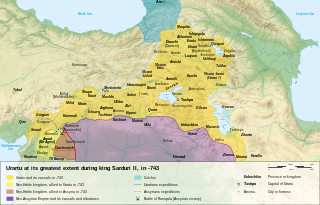

Urartu was an Iron Age kingdom centered around Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands. It extended from the eastern bank of the upper Euphrates River to the western shores of Lake Urmia and from the mountains of northern Iraq to the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. Its kings left behind cuneiform inscriptions in the Urartian language, a member of the Hurro-Urartian language family. Since its re-discovery in the 19th century, Urartu, which is commonly believed to have been at least partially Armenian-speaking, has played a significant role in Armenian nationalism.

The Armeno-Phrygians are a hypothetical people of West Asia during the Bronze Age, the Bronze Age collapse, and its aftermath. They would be the common ancestors of both Phrygians and Proto-Armenians. In turn, Armeno-Phrygians would be the descendants of the Graeco-Phrygians, common ancestors of Greeks, Phrygians, and also of Armenians.

The name Armeno-Phrygian is used for a hypothetical language branch, which would include the languages spoken by the Phrygians and the Armenians, and would be a branch of the Indo-European language family, or a sub-branch of either the proposed "Graeco-Armeno-Aryan" or "Armeno-Aryan" branches. According to this hypothesis, Proto-Armenian was a language descendant from a common ancestor with Phrygian and was closely related to it. Proto-Armenian differentiated from Phrygian by language evolution over time but also by the Hurro-Urartian language substrate influence. Classification is difficult because little is known of Phrygian, but Proto-Armenian arguably forms a subgroup with Greek and Indo-Iranian.

Etiuni was the name of an early Iron Age tribal confederation in northern parts of Araxes River, roughly corresponding to the subsequent Ayrarat Province of the Kingdom of Armenia. Etiuni was frequently mentioned in the records of Urartian kings, who led numerous campaigns into Etiuni territory. It is very likely it was the "Etuna" or "Etina" which contributed to the fall of Urartu, according to Assyrian texts. Some scholars believe it had an Armenian-speaking population.

Paroyr Skayordi or Paroyr, son of Skayordi, was an Armenian king mentioned in the history of Movses Khorenatsi in the context of events of the 7th century BC. Khorenatsi describes him as a descendant of the Armenian patriarch Hayk who helped the Median king "Varbakes" defeat the Assyrian king "Sardanapalus" and received the crown of Armenia in return, becoming "the first to reign in Armenia." Different theories exist about the possible historical identity of Paroyr Skayordi, whose second name is sometimes interpreted as meaning "son of a Saka/Scythian" or "of Saka lineage." According to one view, he is identifiable with the Scythian king Partatua, who lived in the first half of the 7th century BC. Other scholars believe that he was the ruler of Arme-Shupria and allied with the Medes against Assyria around 612 BC. Others believe that he was the ruler of a Scythian land within the Etiuni confederation, which, according to one hypothesis, was the early polity of the Armenians.