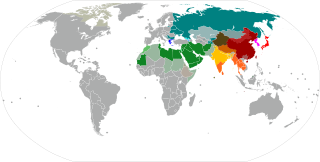

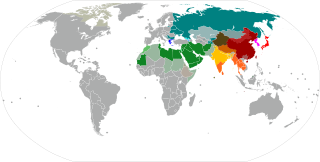

Egyptian hieroglyphs were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 100 distinct characters. Cursive hieroglyphs were used for religious literature on papyrus and wood. The later hieratic and demotic Egyptian scripts were derived from hieroglyphic writing, as was the Proto-Sinaitic script that later evolved into the Phoenician alphabet. Through the Phoenician alphabet's major child systems, the Egyptian hieroglyphic script is ancestral to the majority of scripts in modern use, most prominently the Latin and Cyrillic scripts and the Arabic script, and possibly the Brahmic family of scripts.

A phonetic complement is a phonetic symbol used to disambiguate word characters (logograms) that have multiple readings, in mixed logographic-phonetic scripts such as Egyptian hieroglyphs, Akkadian cuneiform, Japanese, and Mayan. Often they reenforce the communication of the ideogram by repeating the first or last syllable in the term.

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

The Lycian language was the language of the ancient Lycians who occupied the Anatolian region known during the Iron Age as Lycia. Most texts date back to the fifth and fourth century BC. Two languages are known as Lycian: regular Lycian or Lycian A, and Lycian B or Milyan. Lycian became extinct around the beginning of the first century BC, replaced by the Ancient Greek language during the Hellenization of Anatolia. Lycian had its own alphabet, which was closely related to the Greek alphabet but included at least one character borrowed from Carian as well as characters proper to the language. The words were often separated by two points.

Luwian, sometimes known as Luvian or Luish, is an ancient language, or group of languages, within the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. The ethnonym Luwian comes from Luwiya – the name of the region in which the Luwians lived. Luwiya is attested, for example, in the Hittite laws.

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform scripts are marked by and named for the characteristic wedge-shaped impressions which form their signs. Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system and was originally developed to write the Sumerian language of southern Mesopotamia.

Hittite, also known as Nesite, is an extinct Indo-European language that was spoken by the Hittites, a people of Bronze Age Anatolia who created an empire centred on Hattusa, as well as parts of the northern Levant and Upper Mesopotamia. The language, now long extinct, is attested in cuneiform, in records dating from the 17th to the 13th centuries BC, with isolated Hittite loanwords and numerous personal names appearing in an Old Assyrian context from as early as the 20th century BC, making it the earliest attested use of the Indo-European languages.

Palaic is an extinct Indo-European language, attested in cuneiform tablets in Bronze Age Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites. Palaic, which was apparently spoken mainly in northern Anatolia, is generally considered to be one of four primary sub-divisions of the Anatolian languages, alongside Hittite, Luwic and Lydian.

A determinative, also known as a taxogram or semagram, is an ideogram used to mark semantic categories of words in logographic scripts which helps to disambiguate interpretation. They have no direct counterpart in spoken language, though they may derive historically from glyphs for real words, and functionally they resemble classifiers in East Asian and sign languages. For example, Egyptian hieroglyphic determinatives include symbols for divinities, people, parts of the body, animals, plants, and books/abstract ideas, which helped in reading, but none of which were pronounced.

Proto-Anatolian is the proto-language from which the ancient Anatolian languages emerged. As with almost all other proto-languages, no attested writings have been found; the language has been reconstructed by applying the comparative method to all the attested Anatolian languages as well as other Indo-European languages.

Hieroglyphic Luwian (luwili) is a variant of the Luwian language, recorded in official and royal seals and a small number of monumental inscriptions. It is written in a hieroglyphic script known as Anatolian hieroglyphs.

Hittite cuneiform is the implementation of cuneiform script used in writing the Hittite language. The surviving corpus of Hittite texts is preserved in cuneiform on clay tablets dating to the 2nd millennium BC.

A Sumerogram is the use of a Sumerian cuneiform character or group of characters as an ideogram or logogram rather than a syllabogram in the graphic representation of a language other than Sumerian, such as Akkadian, Eblaite, or Hittite. This type of logogram characterized, to a greater or lesser extent, every adaptation of the original Mesopotamian cuneiform system to a language other than Sumerian. The frequency and intensity of their use varied depending on period, style, and genre. In the same way, a written Akkadian word that is used ideographically to represent a language other than Akkadian is known as an Akkadogram.

A writing system comprises a particular set of symbols, called a script, as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. Writing systems can generally be classified according to how symbols function according to these rules, with the most common types being alphabets, syllabaries, and logographies. Alphabets use symbols called letters that correspond to spoken phonemes. Abjads generally only have letters for consonants, while pure alphabets have letters for both consonants and vowels. Abugidas use characters that correspond to consonant–vowel pairs. Syllabaries use symbols called syllabograms to represent syllables or moras. Logographies use characters that represent semantic units, such as words or morphemes.

Šanta (Santa) was a god worshiped in Bronze Age Anatolia by Luwians and Hittites. It is presumed that he was regarded as a warlike deity, and that he could additionally be associated with plagues and possibly with the underworld, though the latter proposal is not universally accepted. In known texts he frequently appears alongside Iyarri, a deity of similar character. He is first attested in documents from Kanesh dated to the Old Assyrian period, and continues to appear in later treaties, ritual texts and theophoric names. He is also present in an offering lists from Emar written in Akkadian, though he did not belong to the local pantheon and rituals involving him were only performed on behalf of the Hittite administration by local inhabitants.

Heterogram is a term used mostly in the study of ancient texts for a special kind of a logogram consisting of the embedded written representation of a word in a foreign language, which does not have a spoken counterpart in the main (matrix) language of the text. In most cases, the matrix and embedded languages share the same script. While from the perspective of the embedded language the word may be written either phonetically or logographically, it is never a phonetic spelling from the point of view of the matrix language of the text, since there is no relationship between the symbols used and the underlying pronunciation of the word in the matrix language.

The House of Astiruwa was the last known dynasty of rulers of Carchemish. The members of this dynasty are best known to us through Hieroglyphic Luwian sources. One member of the House of Astiruwa may also be referred to in Assyrian sources.

Tarḫunz was the weather god and chief god of the Luwians, a people of Bronze Age and early Iron Age Anatolia. He is closely associated with the Hittite god Tarḫunna and the Hurrian god Teshub.

Frederik Christiaan Woudhuizen was a Dutch independent scholar who studied ancient Indo-European languages, hieroglyphic Luvian/Luwian, and Mediterranean protohistory. He was the former editor of Talanta, Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society.

Luwian Studies is an independent, private, non-profit foundation based in Zürich, Switzerland. Its sole purpose is to promote the study of cultures of the second millennium BC in western Asia Minor. The foundation encourages and supports archaeological, linguistic and natural scientific investigations to complete the understanding of Middle and Late Bronze Age Mediterranean cultures. Western Anatolia was, at that point in time, home to groups of people who spoke Luwian, an Indo-European language.