An abugida – sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabet – is a segmental writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit is based on a consonant letter, and vowel notation is secondary, like a diacritical mark. This contrasts with a full alphabet, in which vowels have status equal to consonants, and with an abjad, in which vowel marking is absent, partial, or optional – in less formal contexts, all three types of script may be termed "alphabets". The terms also contrast them with a syllabary, in which a single symbol denotes the combination of one consonant and one vowel.

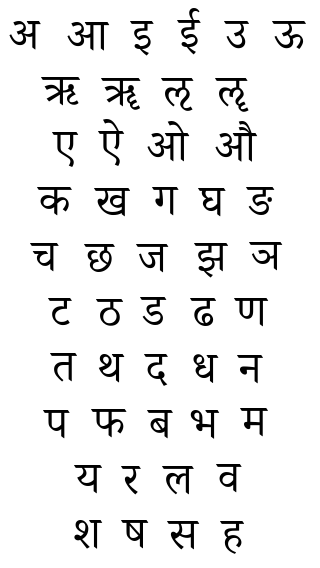

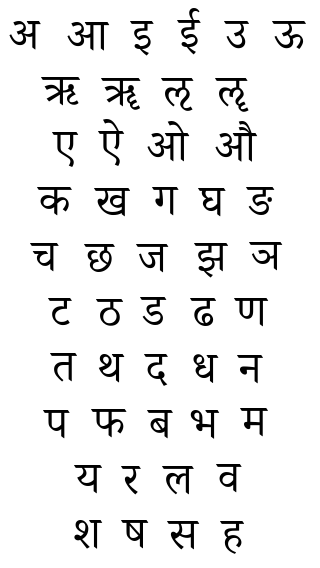

Devanāgarī or Devanagari, also called Nāgari, is a left-to-right abugida, based on the ancient Brāhmi script, used in the northern Indian subcontinent. It is one of the official scripts of the Republic of India and Nepal. It was developed and in regular use by the 7th century CE and achieved its modern form by 1000 CE. The Devanāgari script, composed of 48 primary characters, including 14 vowels and 34 consonants, is the fourth most widely adopted writing system in the world, being used for over 120 languages.

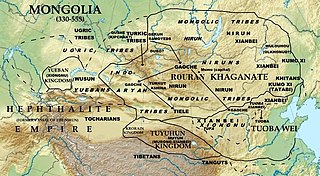

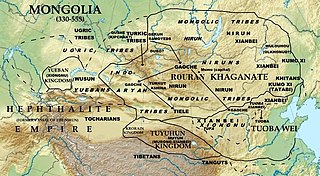

Various Mongolian writing systems have been devised for the Mongolian language over the centuries, and from a variety of scripts. The oldest and native script, called simply the Mongolian script, has been the predominant script during most of Mongolian history, and is still in active use today in the Inner Mongolia region of China and has de facto use in Mongolia.

Calligraphy is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner".

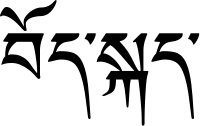

The Tibetan script is a segmental writing system (abugida) of Indic origin used to write certain Tibetic languages, including Tibetan, Dzongkha, Sikkimese, Ladakhi, Jirel and Balti. It has also been used for some non-Tibetic languages in close cultural contact with Tibet, such as Thakali and Old Turkic. The printed form is called uchen script while the hand-written cursive form used in everyday writing is called umê script. This writing system is used across the Himalayas and Tibet.

The Jokhang, also known as the Qoikang Monastery, Jokang, Jokhang Temple, Jokhang Monastery and Zuglagkang, is a Buddhist temple in Barkhor Square in Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Tibetans, in general, consider this temple as the most sacred and important temple in Tibet. The temple is currently maintained by the Gelug school, but they accept worshipers from all sects of Buddhism. The temple's architectural style is a mixture of Indian vihara design, Tibetan and Nepalese design.

Songtsen Gampo, also Songzan Ganbu, was the 33rd Tibetan king and founder of the Tibetan Empire, and is traditionally credited with the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, influenced by his Nepali consort Bhrikuti, of Nepal's Licchavi dynasty, as well as with the unification of what had previously been several Tibetan kingdoms. He is also regarded as responsible for the creation of the Tibetan script and therefore the establishment of Classical Tibetan, the language spoken in his region at the time, as the literary language of Tibet.

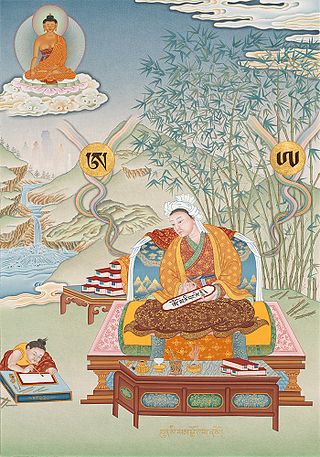

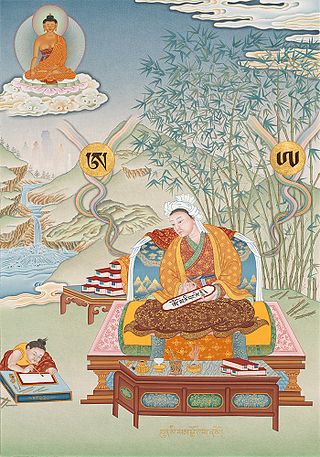

Thonmi Sambhota is traditionally regarded as the inventor of the Tibetan script and author of the Sum cu pa and Rtags kyi 'jug pa in the 7th century CE. Thonmi Sambhota is not mentioned in any of the Old Tibetan Annals or other ancient texts, although the Annals does mention writing shortly after 650. The two treaties attributed to him must postdate the 13th century.

Tuyuhun, also known as Henan and Azha, was a dynastic monarchy established by the nomadic peoples related to the Xianbei in the Qilian Mountains and upper Yellow River valley, in modern Qinghai, China.

Muru Ningba or Meru Nyingba is a small Buddhist monastery located between the larger monasteries of Jokhang and Barkhor in the city of Lhasa, Tibet, China. It was the Lhasa seat of the former State Oracle who had his main residence at Nechung Monastery.

This is a list of topics related to Tibet.

Tibetan calligraphy is the calligraphic tradition of writing the Tibetan language. As in other parts of East Asia, nobles, high lamas, and persons of high rank were expected to have high abilities in calligraphy. However, unlike other East Asian calligraphic traditions, calligraphy was done using a reed pen as opposed to a brush. Tibetan calligraphy is at times more free-flowing than calligraphy involving the descendants of other Brahmi scripts. Given the overriding religious nature of Tibetan culture, many of the traditions in calligraphy come from religious texts, and most Tibetan scribes have a monastic background.

The Valley of the Kings or Chongye Valley branches off the Yarlung Valley to the southwest and contains a series of graveyard tumuli, approximately 27 kilometres (17 mi) south of Tsetang, Tibet, near the town of Qonggyai on Mure Mountain in Qonggyai County of the Shannan Prefecture.

The Zhol outer pillar, or Doring Chima, is a stone pillar which stands outside the historical residential and administrative Zhol village below the Potala Palace, in Lhasa, Tibet. It was erected to commemorate a 783 border treaty between the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty. The pillar is inscribed with an old example of Tibetan writing.

The Old Tibetan Chronicle is a collection of narrative accounts and songs relating to Tibet's Yarlung dynasty and the Tibetan Empire. The three manuscripts that comprise the only extant copies of the Chronicle are among the Dunhuang Manuscripts found in the early 20th century in the so-called "hidden library" at the Mogao Grottoes near Dunhuang, which is believed to have been sealed in the 11th century CE. The Chronicle, together with the Old Tibetan Annals comprise Tibet's earliest extant history.

Pecha is a Tibetan word meaning "book", but in particular, refers to the traditional Tibetan loose-leaf books such as the kangyur, tengyur, and sadhanas. Pechas sometimes have top and bottom cover plates made of wood, cardboard, or other firm materials, and are often seen wrapped in cloth for protection. The word pecha has entered common use in other languages such as English in the Tibetan Buddhist community, evident online in discussion forums and software products that include the word in their names.

The Yarlung dynasty, or Pre-Imperial Tibet, was a proto-historical dynasty in Tibet before the rise of the historical Tibetan Empire in the 7th century.

The Marchen script was a Brahmic abugida which was used for writing the extinct Zhangzhung language. It was derived from the Tibetan script.

Gar Tongtsen Yulsung was a general of the Tibetan Empire who served as Lönchen during the reign of Songtsen Gampo. In many Chinese records, his name was given as Lù Dōngzàn or Lùn Dōngzàn ; both are attempts to transliterate the short form of his title and name, Lön Tongtsen.

Ancient Indian scripts have been used in the history of the Indian subcontinent as writing systems. The Indian subcontinent consists of various separate linguistic communities, each of which share a common language and culture. The people of the ancient India wrote in many scripts which largely have common roots.