Igbo is the principal native language cluster of the Igbo people, an ancient ethnicity in the Southeastern part of Nigeria.

Efik mythology consists of a collection of myths narrated, sung or written down by the Efik people and passed down from generation to generation. Sources of Efik mythology include bardic poetry, art, songs, oral tradition and proverbs. Stories concerning Efik myths include creation myths, supernatural beings, mythical creatures, and warriors. Efik myths were initially told by Efik people and narrated under the moonlight. Myths, legends and historical stories are known in Efik as Mbụk while moonlight plays in Efik are known as Mbre Ọffiọñ.

The Ibibio people are a coastal people in Southern Nigeria. They are mostly found in Akwa Ibom, Cross River State and the Eastern part of Abia State. They are related to the Efik people. During the colonial period in Nigeria, the Ibibio Union asked for recognition by the British as a sovereign nation.

Anaang is an ethnic group in Southern Nigeria, whose land is primarily within 8 of the present 31 Local Government Areas in Akwa Ibom State: Abak, Essien Udim, Etim Ekpo, Ika, Ikot Ekpene, Obot Akara, Oruk Anam, Ukanafun in Akwa Ibom State. The Anaang are the second largest ethnic group after the Ibibios in Akwa Ibom state.

Central Ibibio is the major dialect cluster of the Cross River branch of Benue–Congo. Efik proper has national status in Nigeria and was erroneously made the literary standard of the Ibibio language, though Ibibio proper has more native speakers.

Ekpe, also known as Mgbe/Egbo, is a West African secret society in Nigeria and Cameroon flourishing chiefly among the Efiks. It is also found among a number of other ethnic groups, including the Bahumono of the Cross River State, the Ibibio, the Uruan and the Oron of Akwa Ibom State, Arochukwu and some other parts of Abia State, as well as in the diaspora, such as in Cuba and Brazil. The society is still active at the beginning of the 21st century, now playing more of a ceremonial role.

The Efik are an ethnic group located primarily in southern Nigeria, and western Cameroon. Within Nigeria, the Efik can be found in the present-day Cross River State and Akwa Ibom state. The Efik speak the Efik language which is a member of the Benue–Congo subfamily of the Niger-Congo language group. The Efik refer to themselves as Efik Eburutu, Ifa Ibom, Eburutu and Iboku.

The Aro people or Aros are an Igbo subgroup that originated from the Arochukwu kingdom in present-day Abia state, Nigeria. The Aros can also be found in about 250 other settlements mostly in the Southeastern Nigeria and adjacent areas. The Aros today are classified as Eastern or Cross River Igbos because of their location, mixed origins, culture, and dialect. Their god, Chukwu Abiama, was a key factor in establishing the Aro Confederacy as a regional power in the Niger Delta and Southeastern Nigeria during the 18th and 19th centuries.

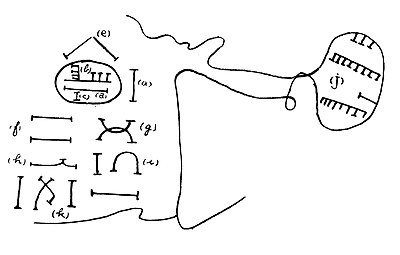

Ekoi people, also known as Ejagham, are an ethnic group in southeastern Nigeria and extending eastward into the southwest region of Cameroon. They speak the Ejagham language. Other Ekoi languages are spoken by related groups, including the Etung, some groups in Ikom, some groups in Ogoja, Ufia, and Yakö. The Ekoi have lived closely with the nearby Efik, Annang, Ibibio, and Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria. The Ekoi are best known for their Ekpe headdresses and the Nsibidi text. Whereas the Igbos are the creators of the Nsibidi ideograms, the Ekoi, like other peoples from the old Cross River region still use them as a part of tradition.

The Oron Nation was a sovereign and egalitarian society from c. 1200 to its forced incorporation into Nigeria in 1914. The Oron people share a strong ancestral lineage with the Efik people in the Cross River State. Some other related indigenous groups include the Uruan, Ibeno and Andoni people, both in the Akwa Ibom State and in the Rivers State, along with the Balondo-ba-Konja, now located in the Congo. The Oron people are a major ethnic group still present in Akwa Ibom.

The Oron people are a multi-ethnic tribal grouping that make up the Akpakip Oro or Oron Nation. The Oron people (Örö) are located primarily in southern Nigeria in the riverine area of Akwa Ibom State and Cross River State and in Cameroon. Akpakip Oro are regarded as an ancient warrior people, speaking the Oron (Oro) language which is in the Cross River language family of the Benue–Congo languages. They are ancestrally related to the Efik people of the Cross River State, the Ibeno and Eastern Obolo in Akwa Ibom, the Andoni people in Rivers State, Ohafia in Abia State and the Balondo-ba-Konja in the Congo.

Uruan is a Local Government Area in Akwa Ibom State, south of Nigeria.

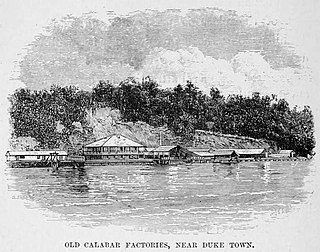

Duke Town, originally known as Atakpa, is an Efik city-state that flourished in the 19th century in what is now southern Nigeria. The City State extended from now Calabar to Bakassi in the east and Oron to the west. Although it is now absorbed into Nigeria, traditional rulers of the state are still recognized. The state occupied what is now the modern city of Calabar.

Cross River is the main river in southeastern Nigeria and gives its name to Cross River State. It originates in Cameroon, where it takes the name of the Manyu River. Although not long by African standards its catchment has high rainfall and it becomes very wide. Over its last 80 kilometres (50 mi) to the sea it flows through swampy rainforest with numerous creeks and forms an inland delta near its confluence with the Calabar River, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) wide and 50 kilometres (31 mi) long between the cities of Oron on the west bank and Calabar, on the east bank, more than 30 kilometres (19 mi) from the open sea. The delta empties into a broad estuary which it shares with a few smaller rivers. At its mouth in the Atlantic Ocean, the estuary is 24 kilometres (15 mi) wide. The eastern side of the estuary is in the neighboring country of Cameroon.

Ibibio is the native language of the Ibibio people of Nigeria, belonging to the Ibibio-Efik dialect cluster of the Cross River languages. The name Ibibio is sometimes used for the entire dialect cluster. In pre-colonial times, it was written with Nsibidi ideograms, similar to Igbo, Efik, Anaang, and Ejagham. Ibibio has also had influences on Afro-American diasporic languages such as AAVE words like buckra which come from the Ibibio word mbakara and in the Afro-Cuban tradition of abakua.

EfikEF-ik is the indigenous language of the Efik people, who are situated in the present-day Cross River state and Akwa Ibom state of Nigeria, as well as in the North-West of Cameroon. The Efik language is mutually intelligible with other lower Cross River languages such as Ibibio, Annang, Oro and Ekid but the degree of intelligibility in the case of Oro and Ekid is unidirectional; in other words, speakers of these languages speak and understand Efik but not vice versa. The Efik vocabulary has been enriched and influenced by external contact with the British, Portuguese and other surrounding communities such as Balondo, Oron, Efut, Okoyong, Efiat and Ekoi (Qua).

The Oroko are an ethnic group in Cameroon. They belong to the coastal Bantu group, widely known as Sawa, and primarily occupy the Ndian and Meme divisions of the Southwest Region of Cameroon. The people predominantly speak Oroko, English, and Cameroon Pidgin English. The Oroko are related to several ethnic groups in Cameroon's coastal areas, with whom they share a common traditional origin, and similar histories and cultures. These include the Bakweri (Kwe), Bakole, Duala, Ewodi, the Bodiman, the Pongo, the Bamboko, the Isubu, the Limba, the Mungo, and the Wovea.

Efik literature is literature spoken or written in the Efik language, particularly by Efik people or speakers of the Efik language. Traditional Efik literature can be classified as follows; Ase, Uto, Mbụk, Ñke and Ikwọ. Other aspects of Efik literature include prose and drama (Mbre).

The Efik calendar is the traditional calendar system of the Efik people located in present-day Nigeria. The calendar consisted of 8 days in a week (urua). Each day was dedicated to a god or goddess greatly revered in the Efik religion. It also consisted of festivals many of which were indefinite. Definite festivals were assigned on specific periods during the year while indefinite festivals or ceremonies occurred due to certain social or political circumstances.