A gift economy or gift culture is a mode of exchange where valuables are not sold, but rather given without an explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards. Social norms and customs govern giving a gift in a gift culture, gifts are not given in an explicit exchange of goods or services for money, or some other commodity or service. This contrasts with a barter economy or a market economy, where goods and services are primarily explicitly exchanged for value received.

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in economic anthropology focus on exchange. In contrast, the Marxian school known as "political economy" focuses on production.

Marcel Mauss was a French sociologist. The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic, sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology. His most famous work is The Gift (1925).

Social exchange theory is a sociological and psychological theory that studies the social behavior in the interaction of two parties that implement a cost-benefit analysis to determine risks and benefits. The theory also involves economic relationships—the cost-benefit analysis occurs when each party has goods that the other parties value. Social exchange theory suggests that these calculations occur in romantic relationships, friendships, professional relationships, and ephemeral relationships as simple as exchanging words with a customer at the cash register. Social exchange theory says that if the costs of the relationship are higher than the rewards, such as if a lot of effort or money were put into a relationship and not reciprocated, then the relationship may be terminated or abandoned.

In cultural anthropology, reciprocity refers to the non-market exchange of goods or labour ranging from direct barter to forms of gift exchange where a return is eventually expected as in the exchange of birthday gifts. It is thus distinct from the true gift, where no return is expected.

Kula, also known as the Kula exchange or Kula ring, is a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring was made famous by the father of modern anthropology, Bronisław Malinowski, who used this test case to argue for the universality of rational decision making, and for the cultural nature of the object of their effort. Malinowski's path-breaking work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), directly confronted the question, "why would men risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets?" Malinowski carefully traced the network of exchanges of bracelets and necklaces across the Trobriand Islands, and established that they were part of a system of exchange, and that this exchange system was clearly linked to political authority. Malinowski's study became the subject of debate with the French anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, author of The Gift. Since then, the Kula ring has been central to the continuing anthropological debate on the nature of gift giving, and the existence of gift economies.

The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies is a 1925 essay by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss that is the foundation of social theories of reciprocity and gift exchange.

Structural anthropology is a school of sociocultural anthropology based on Claude Lévi-Strauss' 1949 idea that immutable deep structures exist in all cultures, and consequently, that all cultural practices have homologous counterparts in other cultures, essentially that all cultures are equitable.

The Moka is a highly ritualized system of exchange in the Mount Hagen area, Papua New Guinea, that has become emblematic of the anthropological concepts of "gift economy" and of "Big man" political system. Moka are reciprocal gifts of pigs through which social status is achieved. Moka refers specifically to the increment in the size of the gift; giving more brings greater prestige to the giver. However, reciprocal gift giving was confused by early anthropologists with profit-seeking, as the lending and borrowing of money at interest.

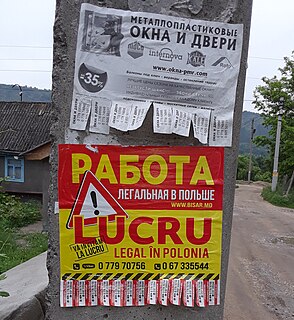

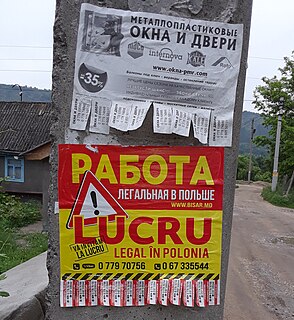

A remittance is a non-commercial transfer of money by a foreign worker, a member of a diaspora community, or a citizen with familial ties abroad, for household income in their home country or homeland. Money sent home by migrants competes with international aid as one of the largest financial inflows to developing countries. Workers' remittances are a significant part of international capital flows, especially with regard to labor-exporting countries.

Mixtec transnational migration is the phenomenon whereby Mixtec people have migrated between Mexico and the United States, for over three generations.

A market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering their goods or services to buyers in exchange for money. It can be said that a market is the process by which the prices of goods and services are established. Markets facilitate trade and enable the distribution and resource allocation in a society. Markets allow any trade-able item to be evaluated and priced. A market emerges more or less spontaneously or may be constructed deliberately by human interaction in order to enable the exchange of rights of services and goods. Markets generally supplant gift economies and are often held in place through rules and customs, such as a booth fee, competitive pricing, and source of goods for sale.

Codevelopment is a trend of thought and a development strategy in development studies which considers migrants to be a developing factor for their countries of origin.

Inalienable possessions are things such as land or objects that are symbolically identified with the groups that own them and so cannot be permanently severed from them. Landed estates in the Middle Ages, for example, had to remain intact and even if sold, they could be reclaimed by blood kin. As a legal classification, inalienable possessions date back to Roman times. According to Barbara Mills, "Inalienable possessions are objects made to be kept, have symbolic and economic power that cannot be transferred, and are often used to authenticate the ritual authority of corporate groups".

Educational capital refers to educational goods that are converted into commodities to be bought, sold, withheld, traded, consumed, and profited from in the educational system. Educational capital can be utilized to produce or reproduce inequality, and it can also serve as a leveling mechanism that fosters social justice and equal opportunity. Educational capital has been the focus of study in Economic anthropology, which provides a framework for understanding educational capital in its endeavor to understand human economic behavior using the tools of both economics and anthropology.

Several authors have used the terms organ gifting and "tissue gifting" to describe processes behind organ and tissue transfers that are not captured by more traditional terms such as donation and transplantation. The concept of "gift of life" in the U.S. refers to the fact that "transplantable organs must be given willingly, unselfishly, and anonymously, and any money that is exchanged is to be perceived as solely for operational costs, but never for the organs themselves". "Organ gifting" is proposed to contrast with organ commodification. The maintenance of a spirit of altruism in this context has been interpreted by some as a mechanism through which the economic relations behind organ/tissue production, distribution, and consumption can be disguised. Organ/tissue gifting differs from commodification in the sense that anonymity and social trust are emphasized to reduce the offer and request of monetary compensation. It is reasoned that the implementation of the gift-giving analogy to organ transactions shows greater respect for the diseased body, honors the donor, and transforms the transaction into a morally acceptable and desirable act that is borne out of voluntarism and altruism.

In anthropology, cultural remittances are the ensembles of ideas, values, and expressive forms introduced into societies of origin by emigrants and their families as they return home, sometimes for the first time, temporary visits, or permanent resettlement. The term, which has been summarized as "product sent back", developed in the early 2000s, is also used to describe "the way that migrants own and build homes in the country of origin."

The archaeology of trade and exchange is a sub-discipline of archaeology that identifies how material goods and ideas moved across human populations. The terms “trade” and “exchange” have slightly different connotations: trade focuses on the long-distance circulation of material goods; exchange considers the transfer of persons and ideas.

Hometown associations (HTAs), also known as hometown societies, are social alliances that are formed among immigrants from the same city or region of origin. Their purpose is to maintain connections with and provide mutual aid to immigrants from a shared place of origin. They may also aim to produce a new sense of transnational community and identity rooted in the migrants' country of origin, extending to the country of settlement. People from a variety of places have formed these associations in several countries, serving a range of purposes.

Christopher A. Gregory is an Australian economic anthropologist. He is based at Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, and has also taught at University of Manchester- where he was made Professor of Political and Economic Anthropology. He studied Economics at University of New South Wales and ANU before pursuing anthropology, following a period in Papua New Guinea. His main research has been in Papua New Guinea and Bastar District, central India, and he also co-authored a research methods manual for economic anthropology, 'Observing the Economy', with Jon Altman.