Rurik was a Varangian chieftain of the Rus' who, according to tradition, was invited to reign in Novgorod in the year 862. The Primary Chronicle states that Rurik was succeeded by his kinsman Oleg who was regent for his infant son Igor.

The Russian Primary Chronicle, commonly shortened to Primary Chronicle, is a chronicle of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110. It is believed to have been originally compiled in or near Kiev in the 1110s. Tradition ascribed its compilation to the monk Nestor beginning in the 17th century, but this is no longer believed to have been the case.

Oleg, also known as Oleg the Wise, was a Varangian prince of the Rus' who became prince of Kiev, and laid the foundations of the Kievan Rus' state.

Igor was Prince of Kiev from 912 to 945. Traditionally, he is considered to be the son of Rurik, who established himself at Novgorod and died in 879 while Igor was an infant. According to the Primary Chronicle, Rurik was succeeded by Oleg, who ruled as regent and was described by the chronicler as being "of his kin".

Nestor the Chronicler or Nestor the Hagiographer was a monk from the Kievan Rus who is known to have written two saints' lives: the Life of the Venerable Theodosius of the Kiev Caves and the Account about the Life and Martyrdom of the Blessed Passion Bearers Boris and Gleb.

The Christianization of Kievan Rus' was a long and complicated process that took place in several stages. In 867, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople told other Christian patriarchs that the Rus' people were converting enthusiastically, but his efforts seem to have entailed no lasting consequences, since the Russian Primary Chronicle and other Slavonic sources describe the tenth-century Rus' as still firmly entrenched in Slavic paganism. The traditional view, as recorded in the Russian Primary Chronicle, is that the definitive Christianization of Kievan Rus' dates happened c. 988, when Vladimir the Great was baptized in Chersonesus (Korsun) and proceeded to baptize his family and people in Kiev. The latter events are traditionally referred to as baptism of Rus' in Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian literature.

Grand prince or great prince is a title of nobility ranked in honour below Emperor, equal to Archduke, King, Grand duke and Prince-Archbishop; above a Sovereign Prince and Duke.

Askold and Dir, mentioned in both the Primary Chronicle, the Novgorod First Chronicle, and the Nikon Chronicle, were the earliest known rulers of Kiev.

Oleg Svyatoslavich ; c. 1052 – 1 August 1115) was a Rus Sviatoslavichi prince whose equivocal adventures ignited political unrest in Kievan Rus' at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries. He reigned as Prince of Chernigov from 1097 to 1115, and was the progenitor of the Olgovichi family.

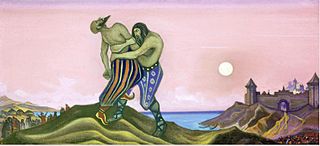

Mstislav Vladimirovich was the earliest attested prince of Tmutarakan and Chernigov in Kievan Rus'. He was a younger son of Vladimir the Great, the grand prince of Kiev. His father appointed him to rule Tmutarakan, an important fortress by the Strait of Kerch, in or after 988.

The Novgorod First Chronicle or The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016–1471 is the oldest extant Rus' chronicle of the Novgorod Republic. Written in Old East Slavic, it reflects a literary tradition about Kievan Rus' which differs from the Primary Chronicle. The later editions of the chronicle reflect the lost Primary Kievan Code of the late 11th century, which contained information not present in the later Primary Chronicle.

The Rus'–Byzantine Treaty of 911 is the most comprehensive and detailed treaty which was allegedly concluded between the Byzantine Empire and Kievan Rus' in the early 10th century. It was preceded by the preliminary treaty of 907. It is considered the earliest written source of Kievan Rus' law. The text of this treaty is only found in the Primary Chronicle (PVL), and its authenticity is therefore difficult to establish.

Rusʹ Khaganate, or kaganate of Rus is a name applied by some modern historians to a hypothetical polity suggested to have existed during a poorly documented period in the history of Eastern Europe between c. 830 and the 890s.

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus', was a state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century. The name was coined by Russian historians in the 19th century. Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse, and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestor, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it, and the name Kievan Rus' derived from what is now the capital of Ukraine. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rus' stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east, uniting the East Slavic tribes.

The Rurik dynasty, also known as the Rurikid or Riurikid dynasty, as well as simply Rurikids or Riurikids, was a noble lineage allegedly founded by the Varangian prince Rurik, who, according to tradition, established himself at Novgorod in the year 862. The Rurikids were the ruling dynasty of Kievan Rus' and its principalities following its disintegration.

Bolokhovians, Bolokhoveni, also Bolokhovens, were a 13th-century ethnic group that resided in the vicinity of the Rus' principalities of Halych, Volhynia and Kiev, in the territory known as the "Bolokhovian Land" centered at the city of Bolokhov or Bolokhovo. Their ethnic identity is uncertain; although Romanian scholars, basing on their ethnonym identify them as Romanians, archeological evidence and the Hypatian Chronicle suggest that they were a Slavic people. Their princes, or knyazes, were in constant conflict with Daniel of Galicia, Prince of Halych and Volhynia, between 1231 and 1257. After the Mongols sacked Kiev in 1240, the Bolokhovians supplied them with troops, but the Bolokhovian princes fled to Poland. The Bolokhovians disappeared after Daniel defeated them in 1257.

The Kievan Chronicle or Kyivan Chronicle is a chronicle of Kievan Rus'. It was written around 1200 in Vydubychi Monastery as a continuation of the Primary Chronicle. It is known from two manuscripts: a copy in the Hypatian Codex, and a copy in the Khlebnikov Codex ; in both codices, it is sandwiched between the Primary Chronicle and the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle. It covers the period from 1118, where the Primary Chronicle ends, until about 1200, although scholars disagree where exactly the Kievan Chronicle ends and the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle begins.

The calling of the Varangians, calling of the (Varangian) princes or invitation to the Varangians is a legend about the origins of the Rus' people, the Rurik dynasty and the Kievan Rus' state, recorded in many divergent versions in various manuscripts and compilations of Rus' chronicles. These include the six main witnesses of the Primary Chronicle and the Novgorod First Chronicle (NPL), as well as later textual witnesses such as the Sofia First Chronicle and the Pskov Third Chronicle.

The Khlebnikov Codex is a codex of Rus' chronicles compiled in c. 1575.

The Conversion of Volodimer is a narrative recorded in several different versions in medieval sources about how Vladimir the Great converted from Slavic paganism to Byzantine Christianity in the 980s.