Sukarno was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type of tomb, or the tomb may be considered to be within the mausoleum.

Presidential elections were held in Indonesia on 5 July and 20 September 2004. As no candidate won a majority in the first round, a runoff was held, in which Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono defeated Megawati Sukarnoputri and was elected president. They were the first direct presidential elections in the history of Indonesia; prior to a 2002 amendment to the Constitution of Indonesia, both the president and vice president had been elected by the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR).

Gelora Bung Karno Main Stadium, formerly Senayan Main Stadium and Gelora Senayan Main Stadium, is a multi-purpose stadium located at the center of the Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex in Central Jakarta, Indonesia. It is mostly used for football matches, and usually used by the Indonesia national football team and Liga 1 club Persija Jakarta. The stadium is named after Sukarno, the then-president of Indonesia, who sparked the idea of building the sports complex.

Imogiri is a royal graveyard complex in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, in south-central Java, Indonesia, as well as a subdistrict under the administration of Bantul Regency. Imogiri is a traditional resting place for the royalty of central Java, including many rulers of the Sultanate of Mataram and the current houses of Surakarta and Yogyakarta Sultanate. The name is Imagiri is derived from the Sanskrit Himagiri, which means 'mountain of snow'. The latter is another name for Himalaya.

Gelora Bung Karno Sports Palace, formerly named Istora Senayan is an indoor sporting arena located in Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex, Jakarta, Indonesia. The capacity of the arena after 2018 reopening is 7,166. This arena is usually used for badminton tournaments, especially the BWF tournaments Indonesia Open and Indonesia Masters. The first event that held in this arena was the 1961 Thomas Cup.

Javanese sacred places are locations on the Island of Java, Indonesia that have significance from either village level through to national level as sacred, and in most cases deserve visitation—usually within the context of ziarah regardless of the ethnicity or religion of the visitor. The dominant form for many places is a sacred grave, or a place associated with persons considered to have special attributes in the past—like Wali Sanga or Royalty.

The Order of Eleventh March, commonly referred to by its syllabic abbreviation Supersemar, was a document signed by the Indonesian President Sukarno on 11 March 1966, giving army commander Lt. Gen. Suharto authority to take whatever measures he "deemed necessary" to restore order to the chaotic situation during the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66. The abbreviation "Supersemar" is also a play on the name of Semar, the mystic and powerful figure who commonly appears in Javanese mythology including wayang puppet shows. The invocation of Semar was presumably intended to help draw on Javanese mythology to lend support to Suharto's legitimacy during the period of the transition of authority from Sukarno to Suharto.

Blitar is a landlocked city in East Java, Indonesia, about 73 km from Malang and 167 km from Surabaya. The area lies within longitude 111° 40' – 112° 09' East and its latitude is 8° 06' South. The city of Blitar lies at an altitude on average 167 metres above sea level, and is an enclave within Blitar Regency which surrounds the city on all sides. It covers an area of 32.57 km2, and had a population of 131,968 at the 2010 Census and 149,149 at the 2020 Census; the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 159,781.

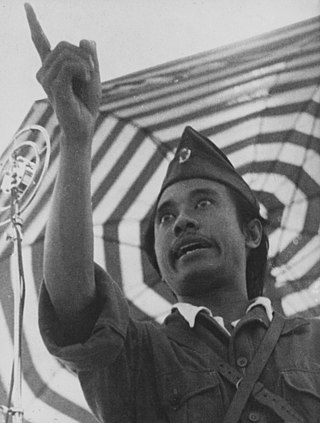

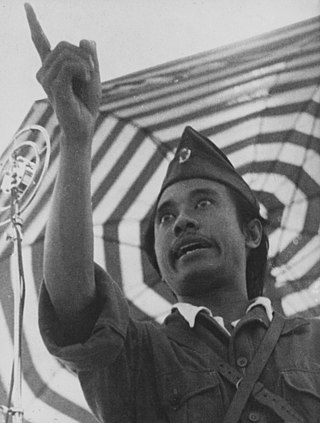

Sutomo, also known as Bung Tomo, was an Indonesian freedom fighter, and is best known for his role as an Indonesian military leader during the Indonesian National Revolution against the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. He played a central role in Battle of Surabaya when the British attacked the city in October and November 1945.

Ratna Sari Dewi Sukarno, widely known in Japan as Dewi Fujin is a Japanese-born Indonesian businesswoman, socialite, television personality and philanthropist. She was one of the wives of the first President of Indonesia, Sukarno.

Astana Giribangun, is a mausoleum complex for the Suharto's family of the former President of Indonesia. The mausoleum is located in Karang Bangun, Matesih, Karanganyar Regency, Central Java province. It is on the slopes of Mount Lawu, approximately 35 kilometres east of the city of Surakarta. The archaic Javanese name translates as "Palace of the risen mountain".

Fatmawati was a National Hero of Indonesia. As the inaugural First Lady of Indonesia, she was the third wife of the first president of Indonesia, Sukarno, and the mother of Indonesia's first female president, Megawati Sukarnoputri. She constructed the first flag flown by Indonesia.

Indonesia and Vietnam established diplomatic relations in 1955. Indonesia has an embassy in Hanoi. Vietnam has an embassy in Jakarta. Both are neighboring nations that have a maritime border which lies on the South China Sea and are members of ASEAN and APEC.

Sidarto Danusubroto is an Indonesian politician and a retired police officer, who is serving as a member of Indonesia's Presidential Advisory Board. A member of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, he previously served as speaker of the People's Consultative Assembly, from 2013 until 2014, following the death of Taufiq Kiemas.

Diah Permana Rachmawati Sukarnoputri was an Indonesian politician. Her father was Indonesia's founding president Sukarno and her elder sister is Megawati Sukarnoputri, who was Indonesia's fifth president.

De-Sukarnoization, also spelled de-Soekarnoization, was a purging policy that existed in Indonesia from the transition to the New Order in 1966 up to the beginning of the Reformation era in 1998, in which President Suharto intended to defame his predecessor Sukarno as well as lessen his presence and downplay his role in Indonesian history.

Diah Mutiara Sukmawati Sukarnoputri is the third daughter of Indonesia’s founding president Sukarno and his wife Fatmawati. Sukmawati is the younger sister of former Indonesian president Megawati Sukarnoputri and politician Rachmawati Sukarnoputri.

Satya Graha was an Indonesian translator and journalist, mostly active during the Sukarno period in the 1950s and the 1960s with the Suluh Indonesia newspaper. Having worked at the newspaper since its founding, he served as its final chief editor before the newspaper's ban and his incarceration in 1965.