In physics, the fundamental interactions or fundamental forces are the interactions that do not appear to be reducible to more basic interactions. There are four fundamental interactions known to exist:

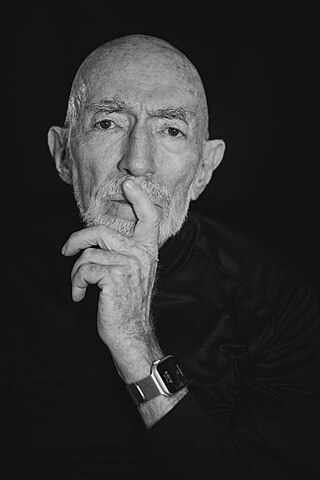

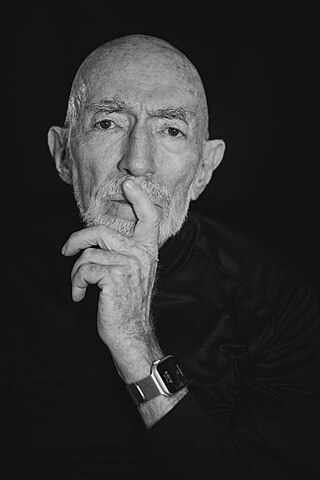

Sir Roger Penrose is a British mathematician, mathematical physicist, philosopher of science and Nobel Laureate in Physics. He is Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics in the University of Oxford, an emeritus fellow of Wadham College, Oxford, and an honorary fellow of St John's College, Cambridge, and University College London.

In physics, gravity (from Latin gravitas 'weight') is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things that have mass. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong interaction, 1036 times weaker than the electromagnetic force and 1029 times weaker than the weak interaction. As a result, it has no significant influence at the level of subatomic particles. However, gravity is the most significant interaction between objects at the macroscopic scale, and it determines the motion of planets, stars, galaxies, and even light.

The Large Scale Structure of Space–Time is a 1973 treatise on the theoretical physics of spacetime by the physicist Stephen Hawking and the mathematician George Ellis. It is intended for specialists in general relativity rather than newcomers.

Kip Stephen Thorne is an American theoretical physicist known for his contributions in gravitational physics and astrophysics. Along with Rainer Weiss and Barry C. Barish, he was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves.

Sir Michael Victor Berry, is a British mathematical physicist at the University of Bristol, England.

Anti-gravity is a hypothetical phenomenon of creating a place or object that is free from the force of gravity. It does not refer to either the lack of weight under gravity experienced in free fall or orbit, or to balancing the force of gravity with some other force, such as electromagnetism and aerodynamic lift. Anti-gravity is a recurring concept in science fiction. Examples are the gravity blocking substance "Cavorite" in H. G. Wells's The First Men in the Moon and the Spindizzy machines in James Blish's Cities in Flight.

Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr. is an American astrophysicist and Nobel Prize laureate in Physics for his discovery with Russell Alan Hulse of a "new type of pulsar, a discovery that has opened up new possibilities for the study of gravitation."

General relativity is a theory of gravitation that was developed by Albert Einstein between 1907 and 1915, with contributions by many others after 1915. According to general relativity, the observed gravitational attraction between masses results from the warping of space and time by those masses.

Bruce Allen is an American physicist and director of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Hannover Germany and leader of the Einstein@Home project for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration. He is also a physics professor at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and the initiator / project leader of smartmontools hard disk utility.

The gravitational interaction of antimatter with matter or antimatter has been observed by physicists. As was the consensus among physicists previously, it was experimentally confirmed that gravity attracts both matter and antimatter at the same rate within experimental error.

The New England Rugby Football Union (NERFU) is a Geographical Union (GU) for rugby union teams in New England.

Martin Bojowald is a German physicist who now works on the faculty of the Penn State Physics Department, where he is a member of the Institute for Gravitation and the Cosmos. Prior to joining Penn State he spent several years at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam, Germany. He works on loop quantum gravity and physical cosmology and is credited with establishing the sub-field of loop quantum cosmology.

Robert M. Wald is an American theoretical physicist and professor at the University of Chicago. He studies general relativity, black holes, and quantum gravity and has written textbooks on these subjects.

The Davis United World College Scholars Program is the world’s largest privately funded international scholarship program. It awards need-based scholarship funding, aka the Shelby Davis Scholarship, to graduates of schools and colleges in the United World Colleges (UWC) movement to study at 94 select partner universities in the United States.

Thanu Padmanabhan was an Indian theoretical physicist and cosmologist whose research spanned a wide variety of topics in gravitation, structure formation in the universe and quantum gravity. He published nearly 300 papers and reviews in international journals and ten books in these areas. He made several contributions related to the analysis and modelling of dark energy in the universe and the interpretation of gravity as an emergent phenomenon. He was a Distinguished Professor at the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) at Pune, India.

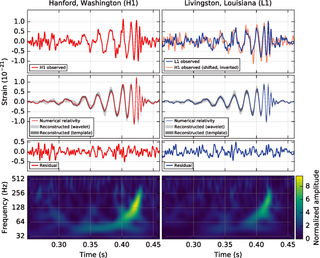

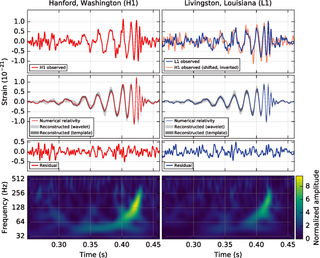

Gravitational-wave astronomy is a subfield of astronomy concerned with the detection and study of gravitational waves emitted by astrophysical sources.

American interest in "gravity control propulsion research" intensified during the early 1950s. Literature from that period used the terms anti-gravity, anti-gravitation, baricentric, counterbary, electrogravitics (eGrav), G-projects, gravitics, gravity control, and gravity propulsion. Their publicized goals were to discover and develop technologies and theories for the manipulation of gravity or gravity-like fields for propulsion. Although general relativity theory appeared to prohibit anti-gravity propulsion, several programs were funded to develop it through gravitation research from 1955 to 1974. The names of many contributors to general relativity and those of the golden age of general relativity have appeared among documents about the institutions that had served as the theoretical research components of those programs. Since its emergence in the 1950s, the existence of the related gravity control propulsion research has not been a subject of controversy for aerospace writers, critics, and conspiracy theory advocates alike, but their rationale, effectiveness, and longevity have been the objects of contested views.

C.V.Vishveshwara was an Indian scientist and black hole physicist. Specializing in Einstein's General Relativity, he worked extensively on the theory of black holes and made major contributions to this field of research since its very beginning. He is popularly known as the 'black hole man of India'.

Ivor Robinson was a British-American mathematical physicist, born and educated in England, noted for his important contributions to the theory of relativity. He was a principal organizer of the Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics.