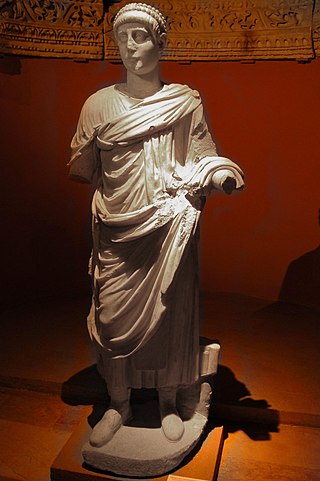

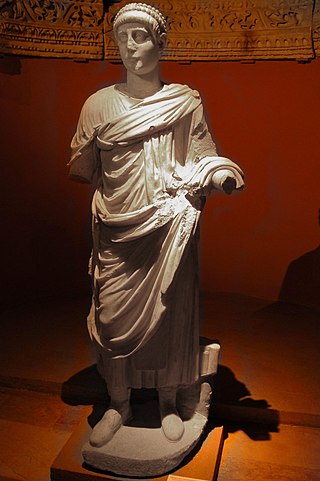

Honorius was Roman emperor from 393 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla. After the death of Theodosius in 395, Honorius, under the regency of Stilicho, ruled the western half of the empire while his brother Arcadius ruled the eastern half. His reign over the Western Roman Empire was notably precarious and chaotic. In 410, Rome was sacked for the first time in almost 800 years.

Magnus Maximus was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian.

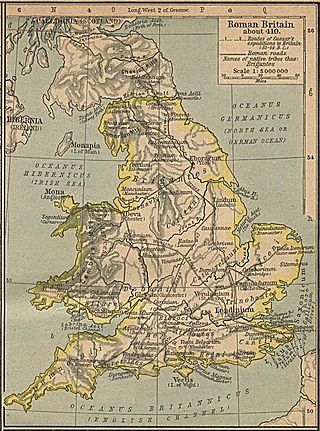

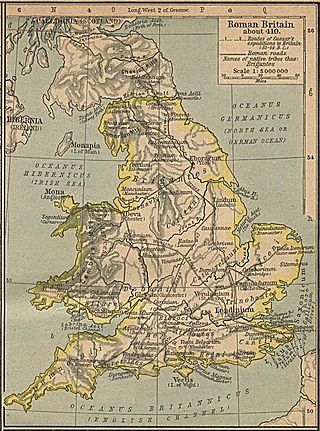

Valentinian I, sometimes called Valentinian the Great, was Roman emperor along with his brother Valens from 364 to 375. During his reign, he fought successfully against the Alamanni, Quadi, and Sarmatians, strengthening the border fortifications and conducting campaigns across the Rhine and Danube. His general Theodosius defeated a revolt in Africa and the Great Conspiracy, a coordinated assault on Roman Britain by Picts, Scoti, and Saxons. Valentinian founded the Valentinianic dynasty, with his sons Gratian and Valentinian II succeeding him in the western half of the empire.

Valentinian II was a Roman emperor in the western part of the Roman empire between AD 375 and 392. He was at first junior co-ruler of his brother, was then sidelined by a usurper, and only after 388 sole ruler, albeit with limited de facto powers.

Constantine III was a common Roman soldier who was declared emperor in Roman Britain in 407 and established himself in Gaul. He was recognised as co-emperor of the Roman Empire from 409 until 411.

Flavius Theodosius, also known as Count Theodosius or Theodosius the Elder, was a senior military officer serving Valentinian I and the western Roman empire during Late Antiquity. Under his command the Roman army defeated numerous threats, incursions, and usurpations. Theodosius was patriarch of the imperial Theodosian dynasty and father of the emperor Theodosius the Great.

The term Western Roman Empire is used in modern historiography to refer to the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent Imperial court—and particularly during the period from 395 to 476, in which there were separate, coequal courts dividing the governance of the empire in the Western provinces from that of the Eastern provinces, with a distinct imperial succession in the separate courts. The terms Western Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire were coined in modern times to describe political entities that were de facto independent; contemporary Romans did not consider the Empire to have been split into two empires but viewed it as a single polity governed by two imperial courts as an administrative expediency. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476, and the Western imperial court in Ravenna was formally dissolved by Justinian in 554. The Eastern imperial court lasted until 1453.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast territory was divided into several successor polities. The Roman Empire lost the strengths that had allowed it to exercise effective control over its Western provinces; modern historians posit factors including the effectiveness and numbers of the army, the health and numbers of the Roman population, the strength of the economy, the competence of the emperors, the internal struggles for power, the religious changes of the period, and the efficiency of the civil administration. Increasing pressure from invading barbarians outside Roman culture also contributed greatly to the collapse. Climatic changes and both endemic and epidemic disease drove many of these immediate factors. The reasons for the collapse are major subjects of the historiography of the ancient world and they inform much modern discourse on state failure.

Attacotti, Atticoti, Attacoti, Atecotti, Atticotti, and Atecutti were Latin names for a people first recorded as raiding Roman Britain between 364 and 368, alongside the Scoti, Picts, Saxons, Roman military deserters and the indigenous Britons themselves. The marauders were defeated by Theodosius in 368.

Valentia was probably one of the Roman provinces of the Diocese of "the Britains" in late Antiquity. Its position, capital, and even existence remain a matter of scholarly debate. It was not mentioned in the Verona List compiled around AD 312 and so was probably formed out of one or more of the other provinces established during the Diocletian Reforms. Some scholars propose Valentia was a new name for the entire diocese, but the List of Offices names it as a consular-rank province along with Maxima Caesariensis and the other equestrian-ranked provinces. Hypotheses for the placement of Valentia include Wales, with its capital at Deva (Chester); Cumbria south of Hadrian's Wall, with its capital at Luguvalium (Carlisle), the lands between the Antonine Wall and Hadrian's Wall, possibly with a capital at Habitancum (Risingham),, although the latter is dismissed by some modern scholars due to the absence of archaeological evidence for a Roman re-occupation of southern Scotland in the fourth century.

This is a chronology of warfare between the Romans and various Germanic peoples between 113 BC and 476. The nature of these wars varied through time between Roman conquest, Germanic uprisings and later Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire that started in the late second century BC. The series of conflicts was one factor which led to the ultimate downfall of the Western Roman Empire in particular and ancient Rome in general in 476.

The Count of the Saxon Shore for Britain was the head of the Saxon Shore military command of the later Roman Empire.

Maximinus was a Roman barrister and Praetorian Prefect of the later fourth century AD.

Valentinus was a Roman criminal and rebel put down after Count Theodosius's arrival in Britain in AD 369.

The Valentinianic or Valentinian dynasty was a ruling house of five generations of dynasts, including five Roman emperors during Late Antiquity, lasting nearly a hundred years from the mid fourth to the mid fifth century. They succeeded the Constantinian dynasty and reigned over the Roman Empire from 364 to 392 and from 425 to 455, with an interregnum (392–423), during which the Theodosian dynasty ruled and eventually succeeded them. The Theodosians, who intermarried into the Valentinian house, ruled concurrently in the east after 379.

The Batavi was an auxilia palatina (infantry) unit of the late Roman army, active between the 4th and the 5th century. It was composed by 500 soldiers and was the heir of those ethnic groups that were initially used as auxiliary units of the Roman army and later integrated in the Roman Empire after the Constitutio Antoniniana. Their name was derived from the people of the Batavi.

The Heruli was an auxilia palatina unit of the Late Roman army, active between the 4th and the 5th century. It was composed of 500 soldiers and was the heir of those ethnic groups that were initially used as auxiliary units of the Roman army and later integrated in the Roman Empire after the Constitutio Antoniniana. Their name was derived from the people of the Heruli. In the sources they are usually recorded together with the Batavi, and it is probable the two units fought together. At the beginning of the 5th century two related units are attested, the Heruli seniores in the West and the Heruli iuniores in the East.

Dagalaifus was a Roman army officer of Germanic descent. A pagan, he served as consul in 366. In the year 361, he was appointed by Emperor Julian as comes domesticorum. He accompanied Julian on his march through Illyricum to quell what remained of the government of Constantius II that year. He led a party into Sirmium that arrested the commander of the resisting army, Lucillianus. In the spring of 363, Dagalaifus was part of Julian's ultimately-disastrous invasion of Persia. On June 26, while still campaigning, Julian was killed in a skirmish. Dagalaifus, who had been with the rear guard, played an important role in the election of the next emperor. The council of military officers finally agreed on the new comes domesticorum, Jovian, to succeed Julian. Jovian was a Christian whose father Varronianus had himself once served as comes domesticorum.

Flavius Jovinus, was a Roman general and consul of the Western Roman Empire. He was of Gaulic or Germanic origin, born and buried in Durocortorum.

Lucillianus was a high-ranking Roman army officer and father-in-law of the emperor Jovian. He fought with success in the war against Persia, and played a part in the execution of the emperor Constantius II's cousin, Gallus. In 361, Lucillianus was kidnapped by the emperor Julian and forced into retirement. He was recalled to service after the accession of his son-in-law Jovian in 363, and given a senior military command, only to be murdered that same year by mutinous troops in Gaul.