Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences, dating back to antiquity, with its origins in the religious, mythological, cosmological, calendrical, and astrological beliefs and practices of prehistory: vestiges of these are still found in astrology, a discipline long interwoven with public and governmental astronomy. It was not completely separated in Europe during the Copernican Revolution starting in 1543. In some cultures, astronomical data was used for astrological prognostication.

"The Balloon-Hoax" is the title used in collections and anthologies of a newspaper article by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1844 in The Sun newspaper in New York. Originally presented as a true story, it detailed European Monck Mason's trip across the Atlantic Ocean in only three days in a gas balloon. It was later revealed as a hoax and the story was retracted two days later.

Frederick William Herschel was a German-British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Herschel. Born in the Electorate of Hanover, William Herschel followed his father into the military band of Hanover, before emigrating to Great Britain in 1757 at the age of nineteen.

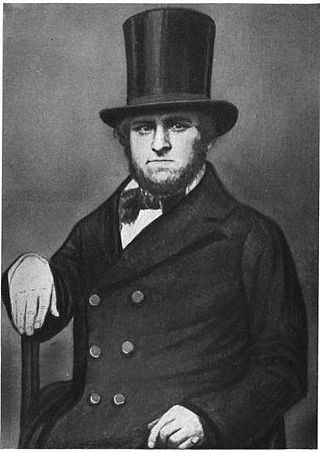

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work.

John Couch Adams was a British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge.

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was a German-born British astronomer, whose most significant contributions to astronomy were the discoveries of several comets, including the periodic comet 35P/Herschel–Rigollet, which bears her name. She was the younger sister of astronomer William Herschel, with whom she worked throughout her career.

Benjamin Henry Day was an American newspaper publisher who founded the New York Sun, the first penny press newspaper in the United States, in 1833.

A transient lunar phenomenon (TLP) or lunar transient phenomenon (LTP) is a short-lived change in light, color or appearance on the surface of the Moon. The term was created by Patrick Moore in his co-authorship of NASA Technical Report R-277 Chronological Catalog of Reported Lunar Events, published in 1968.

The year 1835 in science and technology involved some significant events, listed below.

Johann Hieronymus Schröter was a German astronomer.

The Sun was a New York newspaper published from 1833 until 1950. It was considered a serious paper, like the city's two more successful broadsheets, The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune. The Sun was the first successful penny daily newspaper in the United States, and was for a time, the most successful newspaper in America.

Franz von PaulaGruithuisen was a Bavarian physician and astronomer. He taught medical students before becoming a professor of astronomy at the University of Munich in 1826.

The Moon has appeared in fiction as a setting since at least classical antiquity. Throughout most of literary history, a significant portion of works depicting lunar voyages has been satirical in nature. From the late 1800s onwards, science fiction has successively focused largely on the themes of life on the Moon, first Moon landings, and lunar colonization.

This is a timeline of astronomy. It covers ancient, medieval, Renaissance-era, and finally modern astronomy.

Ewen Adair Whitaker was a British-born astronomer who specialized in lunar studies. During World War II he was engaged in quality control for the lead sheathing of hollow cables strung under the English Channel as part of the "Pipe Line Under The Ocean" Project (PLUTO) to supply gasoline to Allied military vehicles in France. After the war, he obtained a position at the Royal Greenwich Observatory working on the UV spectra of stars, but became interested in lunar studies. As a sideline, Whitaker drew and published the first accurate chart of the South Polar area of the Moon in 1954, and served as director of the Lunar Section of the British Astronomical Association.

In celestial navigation, lunar distance, also called a lunar, is the angular distance between the Moon and another celestial body. The lunar distances method uses this angle and a nautical almanac to calculate Greenwich time if so desired, or by extension any other time. That calculated time can be used in solving a spherical triangle. The theory was first published by Johannes Werner in 1524, before the necessary almanacs had been published. A fuller method was published in 1763 and used until about 1850 when it was superseded by the marine chronometer. A similar method uses the positions of the Galilean moons of Jupiter.

Reverend Thomas Dick, was a British church minister, science teacher and writer, known for his works on astronomy and practical philosophy, combining science and Christianity, and arguing for a harmony between the two.

"The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" (1835) is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe published in the June 1835 issue of the monthly magazine Southern Literary Messenger as "Hans Phaall -- A Tale", intended by Poe to be a hoax.

The planet Neptune was mathematically predicted before it was directly observed. With a prediction by Urbain Le Verrier, telescopic observations confirming the existence of a major planet were made on the night of September 23–24, 1846, at the Berlin Observatory, by astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle, working from Le Verrier's calculations. It was a sensational moment of 19th-century science, and dramatic confirmation of Newtonian gravitational theory. In François Arago's apt phrase, Le Verrier had discovered a planet "with the point of his pen".

Masterpieces of Science Fiction is an anthology of science fiction short stories, edited by Sam Moskowitz. It was first published in hardcover by World Publishing Co. in 1966, and reprinted by Hyperion Press in 1974.