This article has an unclear citation style .(November 2022) |

This article discusses the phonological system of the Greenlandic language.

This article has an unclear citation style .(November 2022) |

This article discusses the phonological system of the Greenlandic language.

The Greenlandic three-vowel system, composed of /i/, /u/, and /a/, is typical for an Eskimo–Aleut language. Double vowels are analyzed as two morae and so they are phonologically a vowel sequence and not a long vowel. They are also orthographically written as two vowels. [2] [3] There is only one diphthong, /ai/, which occurs only at the ends of words. [4]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ( y ~ ɪ ) | ( ʉ ~ ʊ ) | u |

| Mid | ( e ~ ɛ ~ ɐ ) | ( o ~ ɔ ) | |

| Open | a | ( ɑ ) | |

Other authors may use slightly different notation, but Hagerup concludes that the notation is comparable. [8]

The allophonic lowering of /i/ and /u/ before uvular consonants is shown in the modern orthography by writing /i/ and /u/ as ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩ respectively before ⟨q⟩ and ⟨r⟩, as in some orthographies used for Quechua and Aymara. For example:

Nonetheless, still there are some minimal pairs of the lowering allophony, in the case of ⟨rC⟩: aallaat "gun" [aaɬɬaat] vs. aarlaat "February" [ɑɑɬɬaat].

Greenlandic has consonants at five points of articulation: labial, alveolar, palatal, velar and uvular. It distinguishes stops, fricatives, and nasals at the labial, alveolar, velar, and uvular points of articulation. The palatal sibilant [ʃ] has merged with [s] in all dialects except those of the Sisimiut–Maniitsoq–Nuuk–Paamiut area. [9] [10] The labiodental fricative [f] is contrastive only in loanwords. The alveolar stop /t/ is pronounced as an affricate [t͡s] before the high front vowel /i/. Often, Danish loanwords containing ⟨b d g⟩ preserve these in writing, but that does not imply a change in pronunciation, for example ⟨baaja⟩[paːja] "beer" and ⟨Guuti⟩[kuːtˢi] "God"; these are pronounced exactly as /ptk/. [11] Word-final stops may be unreleased or, phrase-internally, even deleted. [12]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral | |||||

| Nasals | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ɴ ⟨rn⟩ [lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Plosives | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | q ⟨q⟩ | ||

| Affricate | t͡s [lower-alpha 2] | |||||

| Fricatives | v ⟨v⟩ [lower-alpha 3] | s ⟨s⟩ | ɬ ⟨ll⟩ [lower-alpha 4] | ʃ [lower-alpha 5] | ɣ ⟨g⟩ | ʁ ⟨r⟩ |

| Liquids | l ⟨l⟩ | |||||

| Semivowel | j ⟨j⟩ | |||||

Also of note is that geminate /vː/ may be pronounced as dento-labial in southern dialects. This is a feature seemingly unique among the world's languages. [13]

The Kalaallisut syllable is simple, allowing syllables of (C)(V)V(C), where C is a consonant and V is a vowel and VV is a double vowel or word-final /ai/. [14] Native words may begin with only a vowel or /p,t,k,q,s,m,n/ and may end only in a vowel or /p,t,k,q/ or rarely /n/. Consonant clusters occur only over syllable boundaries, and their pronunciation is subject to regressive assimilations that convert them into geminates. All non-nasal consonants in a cluster are voiceless. [15]

Greenlandic prosody does not include stress as an autonomous category; instead, prosody is determined by tonal and durational parameters. [3] Intonation is influenced by syllable weight: heavy syllables are pronounced in a way that may be perceived as stress. Heavy syllables include syllables with long vowels and syllables before consonant clusters. The last syllable is stressed in words with fewer than four syllables and without long vowels or consonant clusters. The antepenultimate syllable is stressed in words with more than four syllables that are all light. In words with many heavy syllables, syllables with long vowels are considered heavier than syllables before consonant clusters. [16]

Geminate consonants are pronounced long, almost exactly with the double duration of a single consonant. [17]

Intonation in indicative clauses usually rises on the antepenultimate syllable, falls on the penult and rises on the last syllable. Interrogative intonation rises on the penultimate and falls on the last syllable. [16] [18]

Greenlandic phonology distinguishes itself phonologically from the other Inuit languages by a series of assimilations.

Greenlandic phonology allows clusters of two consonants, but phonetically, the first consonant in a cluster is assimilated to the second one resulting in a geminate consonant. If the first consonant is /ʁ/ or /q/, it nevertheless opens/retracts the preceding vowel, which in case of /i/ and /u/ is then written ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩. Geminate /l/ is pronounced [ɬː]. Geminate /ɣ/ is pronounced [çː~xː]. Geminate /ʁ/ is pronounced [χː]. Geminate /v/ is pronounced [fː] and written ⟨ff, rf⟩. [19]

These assimilations mean that one of the most recognizable Inuktitut words, iglu ("house"), is illu in Greenlandic, where the /ɡl/ consonant cluster of Inuktitut is assimilated into a voiceless alveolar lateral fricative. And the word Inuktitut itself, when translated into Kalaallisut, becomes Inuttut.

When an affix beginning with a consonant is added to a stem that ends in a consonant, the following rules apply (C¹ refers to the final consonant of the stem, C² to the initial consonant of the affix):

/C¹C²/ is realised as [C²C²], e.g. /pl/ → [ll] (more narrowly transcribed [ɬɬ]), except as in the next paragraph. In spelling, ⟨C¹C²⟩ becomes ⟨C²C²⟩, except for ⟨rC²⟩ and *⟨qC²⟩ which become ⟨rC²⟩ (this is necessary to indicate the retracted quality of /a/, while the open qualities of /i/ and /u/ are also indicated by spelling them ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩), except for *⟨rq⟩ and ⟨qq⟩ which become ⟨qq⟩.

If the second consonant is /ʁ/, /v/, or /ɣ/, the following applies:

/C¹ʁ/⟨C¹r⟩ becomes [qq]⟨qq⟩.

/C¹v/ becomes [pp]. In spelling, *⟨C¹v⟩ becomes ⟨pp⟩, except for *⟨rv⟩ and *⟨qv⟩ which become ⟨rp⟩ (this is necessary to indicate the retracted quality of /a/, while the open qualities of /i/ and /u/ are also indicated by spelling them ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩).

/C¹ɣ/⟨C¹g⟩ becomes [kk]⟨kk⟩, except for */ʁɣ/⟨rg⟩ and */qɣ/⟨qg⟩ which become [ʁ]⟨r⟩.

The consonant /v/ has disappeared between /u/ and /i/ or /a/. Therefore, affixes beginning with ⟨-va⟩ or ⟨-vi⟩ have forms without [v] when they are suffixed to stems that end in /u/.

The Old Greenlandic diphthong /au/ has assimilated to /aa/, so when a suffix beginning with /u/ comes after a single /a/, the /u/ becomes /a/. When a suffix beginning with /u/ comes after a double /aa/, a /j/ is instead inserted before the /u/. To summarise: /aau/ → /aaju/, otherwise /au/ → /aa/.

The vowel /i/ of modern Greenlandic is the result of a historic merger of the Proto-Eskimo–Aleut vowels *i and *ɪ. The fourth vowel was still present in Old Greenlandic, as attested by Hans Egede. [20] In modern West Greenlandic, the difference between the two original vowels can be discerned morphophonologically only in certain environments. The vowel that was originally *ɪ has the variant [a] when preceding another vowel and sometimes disappears before certain suffixes. [21]

The degree to which the assimilation of consonant clusters has taken place is an important dialectal feature separating Polar Eskimo, Inuktun, which still allows some ungeminated consonant clusters, from West and East Greenlandic. East Greenlandic (Tunumiit oraasiat) has shifted some geminate consonants, such as [ɬː] to [tː]. Thus, for example, the East Greenlandic name of a particular town is Ittoqqortoormiit, which would appear as Illoqqortoormiut in Kalaallisut. [22] [23]

Approximants are speech sounds that involve the articulators approaching each other but not narrowly enough nor with enough articulatory precision to create turbulent airflow. Therefore, approximants fall between fricatives, which do produce a turbulent airstream, and vowels, which produce no turbulence. This class is composed of sounds like and semivowels like and, as well as lateral approximants like.

In phonetics, rhotic consonants, or "R-like" sounds, are liquid consonants that are traditionally represented orthographically by symbols derived from the Greek letter rho, including ⟨R⟩, ⟨r⟩ in the Latin script and ⟨Р⟩, ⟨p⟩ in the Cyrillic script. They are transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet by upper- or lower-case variants of Roman ⟨R⟩, ⟨r⟩: ⟨r⟩, ⟨ɾ⟩, ⟨ɹ⟩, ⟨ɻ⟩, ⟨ʀ⟩, ⟨ʁ⟩, ⟨ɽ⟩, and ⟨ɺ⟩. Transcriptions for vocalic or semivocalic realisations of underlying rhotics include the ⟨ə̯⟩ and ⟨ɐ̯⟩.

Unless otherwise noted, statements in this article refer to Standard Finnish, which is based on the dialect spoken in the former Häme Province in central south Finland. Standard Finnish is used by professional speakers, such as reporters and news presenters on television.

Non-native pronunciations of English result from the common linguistic phenomenon in which non-native speakers of any language tend to transfer the intonation, phonological processes and pronunciation rules of their first language into their English speech. They may also create innovative pronunciations not found in the speaker's native language.

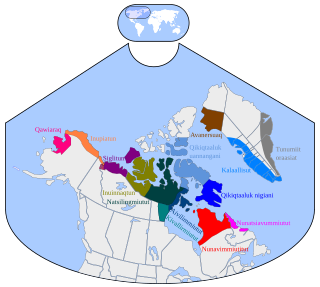

Greenlandic is an Eskimo–Aleut language with about 57,000 speakers, mostly Greenlandic Inuit in Greenland. It is closely related to the Inuit languages in Canada such as Inuktitut. It is the most widely spoken Eskimo–Aleut language. In June 2009, the government of Greenland, the Naalakkersuisut, made Greenlandic the sole official language of the autonomous territory, to strengthen it in the face of competition from the colonial language, Danish. The main variety is Kalaallisut, or West Greenlandic. The second variety is Tunumiit oraasiat, or East Greenlandic. The language of the Inughuit of Greenland, Inuktun or Polar Eskimo, is a recent arrival and a dialect of Inuktitut.

While many languages have numerous dialects that differ in phonology, contemporary spoken Arabic is more properly described as a continuum of varieties. This article deals primarily with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which is the standard variety shared by educated speakers throughout Arabic-speaking regions. MSA is used in writing in formal print media and orally in newscasts, speeches and formal declarations of numerous types.

English phonology is the system of speech sounds used in spoken English. Like many other languages, English has wide variation in pronunciation, both historically and from dialect to dialect. In general, however, the regional dialects of English share a largely similar phonological system. Among other things, most dialects have vowel reduction in unstressed syllables and a complex set of phonological features that distinguish fortis and lenis consonants.

Esperanto is a constructed international auxiliary language designed to have a simple phonology. The creator of Esperanto, L. L. Zamenhof, described Esperanto pronunciation by comparing the sounds of Esperanto with the sounds of several major European languages.

The phonological system of the Polish language is similar in many ways to those of other Slavic languages, although there are some characteristic features found in only a few other languages of the family, such as contrasting postalveolar and alveolo-palatal fricatives and affricates. The vowel system is relatively simple, with just six oral monophthongs and arguably two nasals in traditional speech, while the consonant system is much more complex.

This article describes those aspects of the phonological history of the English language which concern consonants.

The phonology of Bengali, like that of its neighbouring Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, is characterised by a wide variety of diphthongs and inherent back vowels.

The Awngi language, in older publications also called Awiya, is a Central Cushitic language spoken by the Awi people, living in Central Gojjam in northwestern Ethiopia.

Inuktun is the language of approximately 1,000 indigenous Inughuit, inhabiting the world's northernmost settlements in Qaanaaq and the surrounding villages in northwestern Greenland.

This article discusses the phonology of the Inuit languages. Unless otherwise noted, statements refer to Inuktitut dialects of Canada.

This article discusses the phonological system of standard Russian based on the Moscow dialect. For an overview of dialects in the Russian language, see Russian dialects. Most descriptions of Russian describe it as having five vowel phonemes, though there is some dispute over whether a sixth vowel,, is separate from. Russian has 34 consonants, which can be divided into two types:

Adyghe is a language of the Northwest Caucasian family which, like the other Northwest Caucasian languages, is very rich in consonants, featuring many labialized and ejective consonants. Adyghe is phonologically more complex than Kabardian, having the retroflex consonants and their labialized forms.

Kerkrade dialect is a Ripuarian dialect spoken in Kerkrade and its surroundings, including Herzogenrath in Germany. It is spoken in all social classes, but the variety spoken by younger people in Kerkrade is somewhat closer to Standard Dutch.

Hittite phonology is the description of the reconstructed phonology or pronunciation of the Hittite language. Because Hittite as a spoken language is extinct, thus leaving no living daughter languages, and no contemporary descriptions of the pronunciation are known, little can be said with certainty about the phonetics and the phonology of the language. Some conclusions can be made, however, by noting its relationship to the other Indo-European languages, by studying its orthography and by comparing loanwords from nearby languages.