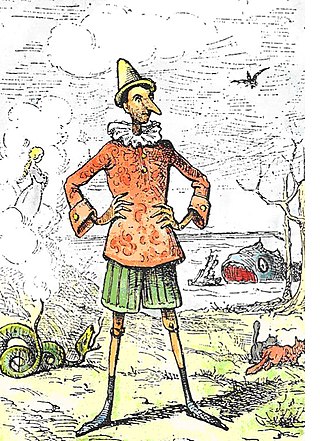

The Epimenides paradox reveals a problem with self-reference in logic. It is named after the Cretan philosopher Epimenides of Knossos who is credited with the original statement. A typical description of the problem is given in the book Gödel, Escher, Bach, by Douglas Hofstadter:

Epimenides was a Cretan who made the immortal statement: "All Cretans are liars."

A false dilemma, also referred to as false dichotomy or false binary, is an informal fallacy based on a premise that erroneously limits what options are available. The source of the fallacy lies not in an invalid form of inference but in a false premise. This premise has the form of a disjunctive claim: it asserts that one among a number of alternatives must be true. This disjunction is problematic because it oversimplifies the choice by excluding viable alternatives, presenting the viewer with only two absolute choices when in fact, there could be many.

In philosophy and logic, the classical liar paradox or liar's paradox or antinomy of the liar is the statement of a liar that they are lying: for instance, declaring that "I am lying". If the liar is indeed lying, then the liar is telling the truth, which means the liar just lied. In "this sentence is a lie" the paradox is strengthened in order to make it amenable to more rigorous logical analysis. It is still generally called the "liar paradox" although abstraction is made precisely from the liar making the statement. Trying to assign to this statement, the strengthened liar, a classical binary truth value leads to a contradiction.

Truth or verity is the property of being in accord with fact or reality. In everyday language, truth is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences.

A hoax is a widely publicized falsehood so fashioned as to invite reflexive, unthinking acceptance by the greatest number of people of the most varied social identities and of the highest possible social pretensions to gull its victims into putting up the highest possible social currency in support of the hoax.

Deception is an act or statement that misleads, hides the truth, or promotes a belief, concept, or idea that is not true. This occurs when a deceiver uses information against a person to make them believe an idea is true. Deception can be used with both verbal and nonverbal messages. The person creating the deception knows it to be false while the receiver of the message has a tendency to believe it. It is often done for personal gain or advantage. Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda and sleight of hand as well as distraction, camouflage or concealment. There is also self-deception, as in bad faith. It can also be called, with varying subjective implications, beguilement, deceit, bluff, mystification, ruse, or subterfuge.

A lie is an assertion that is believed to be false, typically used with the purpose of deceiving or misleading someone. The practice of communicating lies is called lying. A person who communicates a lie may be termed a liar. Lies can be interpreted as deliberately false statements or misleading statements, though not all statements that are literally false are considered lies – metaphors, hyperboles, and other figurative rhetoric are not intended to mislead, while lies are explicitly meant for literal interpretation by their audience. Lies may also serve a variety of instrumental, interpersonal, or psychological functions for the individuals who use them.

Moral skepticism is a class of meta-ethical theories all members of which entail that no one has any moral knowledge. Many moral skeptics also make the stronger, modal claim that moral knowledge is impossible. Moral skepticism is particularly opposed to moral realism: the view that there are knowable and objective moral truths.

The Gettier problem, in the field of epistemology, is a landmark philosophical problem concerning the understanding of descriptive knowledge. Attributed to American philosopher Edmund Gettier, Gettier-type counterexamples challenge the long-held justified true belief (JTB) account of knowledge. The JTB account holds that knowledge is equivalent to justified true belief; if all three conditions are met of a given claim, then we have knowledge of that claim. In his 1963 three-page paper titled "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?", Gettier attempts to illustrate by means of two counterexamples that there are cases where individuals can have a justified, true belief regarding a claim but still fail to know it because the reasons for the belief, while justified, turn out to be false. Thus, Gettier claims to have shown that the JTB account is inadequate because it does not account for all of the necessary and sufficient conditions for knowledge.

Cognitivism is the meta-ethical view that ethical sentences express propositions and can therefore be true or false, which noncognitivists deny. Cognitivism is so broad a thesis that it encompasses moral realism, ethical subjectivism, and error theory.

Self-deception is a process of denying or rationalizing away the relevance, significance, or importance of opposing evidence and logical argument. Self-deception involves convincing oneself of a truth so that one does not reveal any self-knowledge of the deception.

Evidentialism is a thesis in epistemology which states that one is justified to believe something if and only if that person has evidence which supports said belief. Evidentialism is, therefore, a thesis about which beliefs are justified and which are not.

Bad faith is a sustained form of deception which consists of entertaining or pretending to entertain one set of feelings while acting as if influenced by another. It is associated with hypocrisy, breach of contract, affectation, and lip service. It may involve intentional deceit of others, or self-deception.

In logic and philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic. It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy where deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic.

A truth-bearer is an entity that is said to be either true or false and nothing else. The thesis that some things are true while others are false has led to different theories about the nature of these entities. Since there is divergence of opinion on the matter, the term truth-bearer is used to be neutral among the various theories. Truth-bearer candidates include propositions, sentences, sentence-tokens, statements, beliefs, thoughts, intuitions, utterances, and judgements but different authors exclude one or more of these, deny their existence, argue that they are true only in a derivative sense, assert or assume that the terms are synonymous, or seek to avoid addressing their distinction or do not clarify it.

Propaganda techniques are methods used in propaganda to convince an audience to believe what the propagandist wants them to believe. Many propaganda techniques are based on socio-psychological research. Many of these same techniques can be classified as logical fallacies or abusive power and control tactics.

Interpersonal deception theory (IDT) is one of a number of theories that attempts to explain how individuals handle actual deception at the conscious or subconscious level while engaged in face-to-face communication. The theory was put forth by David Buller and Judee Burgoon in 1996 to explore this idea that deception is an engaging process between receiver and deceiver. IDT assumes that communication is not static; it is influenced by personal goals and the meaning of the interaction as it unfolds. IDT is no different from other forms of communication since all forms of communication are adaptive in nature. The sender's overt communications are affected by the overt and covert communications of the receiver, and vice versa. IDT explores the interrelation between the sender's communicative meaning and the receiver's thoughts and behavior in deceptive exchanges.

The illusory truth effect is the tendency to believe false information to be correct after repeated exposure. This phenomenon was first identified in a 1977 study at Villanova University and Temple University. When truth is assessed, people rely on whether the information is in line with their understanding or if it feels familiar. The first condition is logical, as people compare new information with what they already know to be true. Repetition makes statements easier to process relative to new, unrepeated statements, leading people to believe that the repeated conclusion is more truthful. The illusory truth effect has also been linked to hindsight bias, in which the recollection of confidence is skewed after the truth has been received.

Truth-default theory (TDT) is a communication theory which predicts and explains the use of veracity and deception detection in humans. It was developed upon the discovery of the veracity effect - whereby the proportion of truths versus lies presented in a judgement study on deception will drive accuracy rates. This theory gets its name from its central idea which is the truth-default state. This idea suggests that people presume others to be honest because they either don't think of deception as a possibility during communicating or because there is insufficient evidence that they are being deceived. Emotions, arousal, strategic self-presentation, and cognitive effort are nonverbal behaviors that one might find in deception detection. Ultimately this theory predicts that speakers and listeners will default to use the truth to achieve their communicative goals. However, if the truth presents a problem, then deception will surface as a viable option for goal attainment.