Thor Heyerdahl KStJ was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in biology with specialization in zoology, botany and geography.

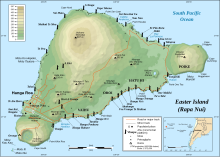

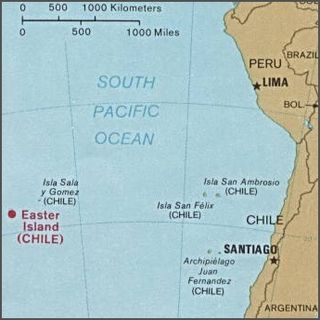

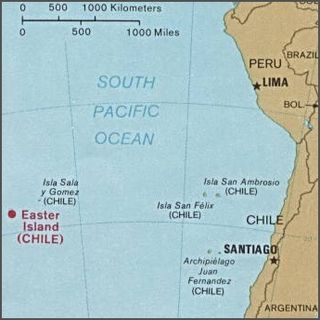

Easter Island is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, called moai, which were created by the early Rapa Nui people. In 1995, UNESCO named Easter Island a World Heritage Site, with much of the island protected within Rapa Nui National Park.

The Kon-Tiki expedition was a 1947 journey by raft across the Pacific Ocean from South America to the Polynesian islands, led by Norwegian explorer and writer Thor Heyerdahl. The raft was named Kon-Tiki after the Inca god Viracocha, for whom "Kon-Tiki" was said to be an old name. Heyerdal’s book on the expedition was entitled The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas. A 1950 documentary film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. A 2012 dramatized feature film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

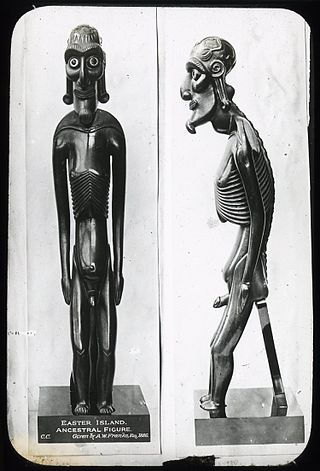

Moai or moʻai are monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui people on Rapa Nui in eastern Polynesia between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but hundreds were transported from there and set on stone platforms called ahu around the island's perimeter. Almost all moai have overly large heads, which comprise three-eighths the size of the whole statue. They have no legs. The moai are chiefly the living faces of deified ancestors. The statues still gazed inland across their clan lands when Europeans first visited the island in 1722, but all of them had fallen by the latter part of the 19th century. The moai were toppled in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, possibly as a result of European contact or internecine tribal wars.

The Rapa Nui are the indigenous Polynesian peoples of Easter Island. The easternmost Polynesian culture, the descendants of the original people of Easter Island make up about 60% of the current Easter Island population and have a significant portion of their population residing in mainland Chile. They speak both the traditional Rapa Nui language and the primary language of Chile, Spanish. At the 2017 census there were 7,750 island inhabitants—almost all living in the village of Hanga Roa on the sheltered west coast.

Rapa-Nui is a 1994 American historical action-adventure film directed by Kevin Reynolds and coproduced by Kevin Costner, who starred in Reynolds's previous film, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). The plot is based on Rapanui legends of Easter Island, Chile, in particular the race for the sooty tern's egg in the Birdman Cult.

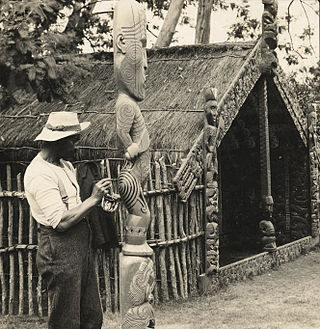

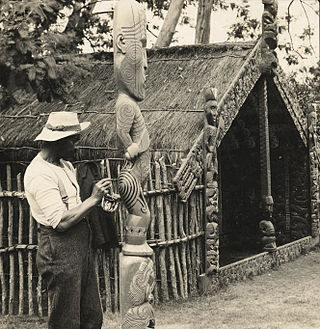

Aku-Aku: the Secret of Easter Island is a 1957 book by Thor Heyerdahl published in Norwegian, Swedish, Danish and Finnish, and in French and English the following year. The book describes the 1955–1956 Norwegian Archaeological Expedition's investigations of Polynesian history and culture at Easter Island, the Austral Islands of Rapa Iti and Raivavae, and the Marquesas Islands of Nuku Hiva and Hiva Oa. Visits to Pitcairn Island, Mangareva and Tahiti are described as well.

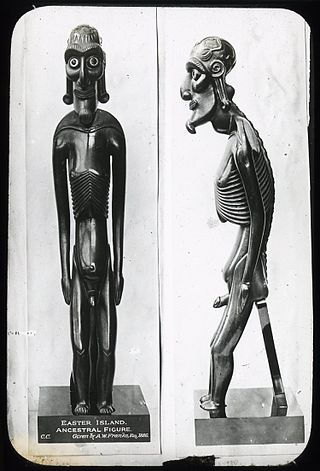

In Māori mythology, Tiki is the first man created by either Tūmatauenga or Tāne. He found the first woman, Marikoriko, in a pond; she seduced him and he became the father of Hine-kau-ataata. By extension, a tiki is a large or small wooden, pounamu or stone carving in humanoid form, notably worn on the neck as a hei-tiki, although this is a somewhat archaic usage in the Māori language. Hei-tiki are often considered taonga, especially if they are older and have been passed down throughout multiple generations. Carvings similar to ngā tiki and coming to represent deified ancestors are found in most Polynesian cultures. They often serve to mark the boundaries of sacred or significant sites. In the Western world, Tiki culture, a movement inspired by various Pacific cultures, has become popular in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Hotu Matuꞌa was the legendary first settler and ariki mau of Easter Island and ancestor of the Rapa Nui people. Hotu Matuꞌa and his two-canoe colonising party were Polynesians from the now unknown land of Hiva. They landed at Anakena beach and his people spread out across the island, sub-divided it between clans claiming descent from his sons, and lived for more than a thousand years in their isolated island home at the southeastern tip of the Polynesian Triangle.

Easter Island was traditionally ruled by a monarchy, with a king as its leader.

Rapa Nui mythology, also known as Pascuense mythology or Easter Island mythology, refers to the native myths, legends, and beliefs of the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island in the south eastern Pacific Ocean.

Anakena is a white coral sand beach in Rapa Nui National Park on Rapa Nui, a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. Anakena has two ahus; Ahu-Ature has a single moai and Ahu Nao-Nao has seven, two of which have deteriorated. It also has a palm grove and a car park.

Ahu Tongariki is the largest ahu on Easter Island. Its moais were toppled during the island's civil wars, and in the twentieth century the ahu was swept inland by a tsunami. It has since been restored and has fifteen moai, including one that weighs eighty-six tonnes, the heaviest ever erected on the island. Ahu Tongariki is one kilometer from Rano Raraku and Poike in the Hotu-iti area of Rapa Nui National Park. All the moai here face sunset during the winter solstice.

Geologically one of the youngest inhabited territories on Earth, Easter Island, located in the mid-Pacific Ocean, was, for most of its history, one of the most isolated. Its inhabitants, the Rapa Nui, have endured famines, epidemics of disease, civil war, environmental collapse, slave raids, various colonial contacts, and have seen their population crash on more than one occasion. The ensuing cultural legacy has brought the island notoriety out of proportion to the number of its inhabitants.

Father Sebastian Englert OFM Cap., was a Capuchin Franciscan friar, Roman Catholic priest, missionary, linguist and ethnologist from Germany. He is known for his pioneering work on Easter Island, where the Father Sebastian Englert Anthropological Museum is named after him.

William Thomas Mulloy Jr. was an American anthropologist. While his early research established him as a formidable scholar and skillful fieldwork supervisor in the province of North American Plains archaeology, he is best known for his studies of Polynesian prehistory, especially his investigations into the production, transportation and erection of the monumental statuary on Rapa Nui known as moai.

Hotu-iti is an area of southeastern Easter Island that takes its name from a local clan. Located in Rapa Nui National Park, the area includes Rano Raraku crater, the Ahu Tongariki site, and a small bay. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Hotu-iti clan was one of two polities on Easter Island.

Gonzalo Figueroa Garcia Huidobro, often referred to simply as Gonzalo Figueroa, was an archaeologist and authority on the conservation of the archaeological heritage of Rapa Nui. Figueroa's work included participating in Thor Heyerdahl's Rapa Nui expedition, restoring Ahu Akivimoai with William Mulloy, and working generally for over four decades to conserve and, in some cases, restore the archaeological monuments of Rapa Nui for future generations.

As in other Polynesian islands, Rapa Nui tattooing had a fundamentally spiritual connotation. In some cases the tattoos were considered a receptor for divine strength or mana. They were manifestations of the Rapa Nui culture. Priests, warriors and chiefs had more tattoos than the rest of the population, as a symbol of their hierarchy. Both men and women were tattooed to represent their social class.

Aku-Aku, also known as Aku, Akuaku or Varua, are humanoid spirits in Rapa Nui mythology of the Easter Island.