Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist governments throughout the 20th century. It was developed in Russia by Joseph Stalin and drew on elements of Bolshevism, orthodox Marxism, and Leninism. It was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, Soviet satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various countries in the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World during the Cold War, as well as the Communist International after Bolshevization.

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social change in the Russian Empire, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government following two successive revolutions and a bloody civil war. The Russian Revolution can also be seen as the precursor for the other European revolutions that occurred during or in the aftermath of World War I, such as the German Revolution of 1918–1919.

Bolshevism is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, focused on overthrowing the existing capitalist state system, seizing power and establishing the "dictatorship of the proletariat".

The Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, also known as Soviet Kazakhstan, the Kazakh SSR, or simply Kazakhstan, was one of the transcontinental constituent republics of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Located in northern Central Asia, it was created on 5 December 1936 from the Kazakh ASSR, an autonomous republic of the Russian SFSR.

The Treaty of Rapallo was an agreement signed on 16 April 1922 between the German Reich and Soviet Russia under which both renounced all territorial and financial claims against each other and opened friendly diplomatic relations. The treaty was negotiated by Russian Foreign Minister Georgi Chicherin and German Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau. It was a major victory for Russia especially and also Germany, and a major disappointment to France and the United Kingdom. The term "spirit of Rapallo" was used for an improvement in friendly relations between Germany and Russia.

An index of articles related to the former nation known as the Soviet Union. It covers the Soviet revolutionary period until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This list includes topics, events, persons and other items of national significance within the Soviet Union. It does not include places within the Soviet Union, unless the place is associated with an event of national significance. This index also does not contain items related to Soviet Military History.

Stanisław Vikentyevich Kosior, sometimes spelled Kossior, was a Soviet politician who was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Deputy Premier of the Soviet Union and member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). He and his wife were both executed during the Great Purge.

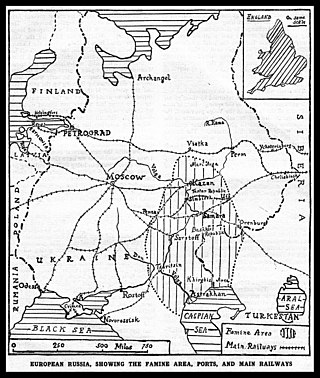

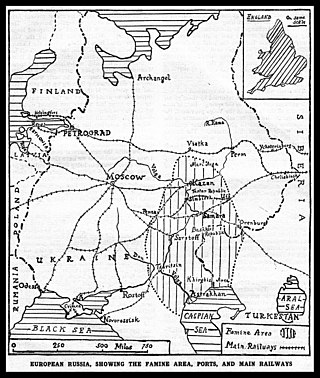

The Russian famine of 1921–1922, also known as the Povolzhye famine, was a severe famine in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic that began early in the spring of 1921 and lasted until 1922. The famine resulted from the combined effects of severe drought, the continued effects of World War I, economic disturbance from the Russian Revolution, the Russian Civil War, and failures in the government policy of war communism. It was exacerbated by rail systems that could not distribute food efficiently.

Isaac Nachman Steinberg was a lawyer, Socialist Revolutionary, politician, a leader of the Jewish Territorialist movement and writer in Soviet Russia and in exile.

Grigory Ivanovich Petrovsky was a Ukrainian Soviet politician and Old Bolshevik. He participated in signing the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Petrovsky was Communist Party leader in Ukraine until 1938, and one of the officials responsible for implementing Stalin's policy of collectivization.

Dekulakization was the Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of kulaks and their families. Redistribution of farmland started in 1917 and lasted until 1933, but was most active in the 1929–1932 period of the first five-year plan. To facilitate the expropriations of farmland, the Soviet government announced the "liquidation of the kulaks as a class" on 27 December 1929, portraying kulaks as class enemies of the Soviet Union.

The history of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (USSR) reflects a period of change for both Russia and the world. Though the terms "Soviet Russia" and "Soviet Union" often are synonymous in everyday speech, when referring to the foundations of the Soviet Union, "Soviet Russia" often specifically refers to brief period between the October Revolution of 1917 and the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922.

Kulak, also kurkul or golchomag, was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over 8 acres of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and Azerbaijan, kulak became a vague reference to property ownership among peasants who were considered hesitant allies of the Bolshevik Revolution. In Ukraine during 1930–1931, there also existed a term of podkulachnik ; these were considered "sub-kulaks".

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat, or working class, holds control over state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the transitional phase from a capitalist and a communist economy, whereby the post-revolutionary state seizes the means of production, mandates the implementation of direct elections on behalf of and within the confines of the ruling proletarian state party, and institutes elected delegates into representative workers' councils that nationalise ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership. During this phase, the administrative organizational structure of the party is to be largely determined by the need for it to govern firmly and wield state power to prevent counterrevolution, and to facilitate the transition to a lasting communist society.

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin encouraged the theory of the possibility of constructing socialism in the Soviet Union. The theory was eventually adopted as Soviet state policy.

Democratic centralism is the organisational principle of communist states and of most communist parties to reach dictatorship of the proletariat. In practice, democratic centralism means that political decisions reached by voting processes are binding upon all members of the political party. It is mainly associated with Leninism, wherein the party's political vanguard of revolutionaries practice democratic centralism to select leaders and officers, determine policy, and execute it.

"To each according to his contribution" is a principle of distribution considered to be one of the defining features of socialism. It refers to an arrangement whereby individual compensation is representative of one's contribution to the social product in terms of effort, labor and productivity. This is in contrast to the method of distribution and compensation in capitalism, an economic and political system in which property owners can receive income by virtue of ownership irrespective of their contribution to the social product.

Putinism is the social, political, and economic system of Russia formed during the political leadership of Vladimir Putin. It is characterized by the concentration of political and financial powers in the hands of "siloviks", current and former "people with shoulder marks", coming from a total of 22 governmental enforcement agencies, the majority of them being the Federal Security Service (FSB), Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia, Armed Forces of Russia, and National Guard of Russia. According to Arnold Beichman, "Putinism in the 21st century has become as significant a watchword as Stalinism was in the 20th."

The First All-Union Congress of Soviets was a congress of representatives of Soviets of workers, peasants and Red Army deputies, held on December 30, 1922 in Moscow. The congress was attended by 2215 delegates. Kalinin was elected chairman of the congress, but Vladimir Lenin, who was not present at the congress due to illness, was elected honorary chairman of the congress. More than 90% of the delegates were members of the Russian Communist Party, 2 left-wing social federalists of the Caucasus, 1 anarchist and 1 member of the Jewish Social Democratic Party.

Vasiliy Nikolayevich Mantsev was a Russian revolutionary and high-ranking official of the Cheka.