Helen Augusta Howard (May 11, 1865 - June 10, 1934) was an American suffragist and philanthropist. Howard was born in Columbus, Georgia, and was one of the founding members of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA).

Helen Augusta Howard (May 11, 1865 - June 10, 1934) was an American suffragist and philanthropist. Howard was born in Columbus, Georgia, and was one of the founding members of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA).

Howard was born on May 11, 1865, in Columbus, Georgia, and was one of fifteen siblings. [1] Howard was the youngest child and grew up on the family home, Sherwood Hall (their antebellum home). [2] [3] Howard's father died when she has younger so her mother had difficulties paying for the taxes on Sherwood Hall. [1] Howard was frustrated that women had to pay taxes yet where not represented in government and could not vote. [4] She studied for two years in Staunton, Virginia, and was interested in the writings of John Stuart Mill. [5]

In 1890, Miss Howard, her mother, and her sisters organized the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA). [3] [6] The purpose of the association was to make people more aware of the inequality in voting practices and not to directly affect legislation. The women of the group did not see themselves as a political group. Two main arguments for suffrage the women used were (1) women are taxed therefore they should be represented and (2) democracy derives its power from those who are governed and women are governed. In 1894, Howard spoke at the National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in Washington, D.C., and convinced the delegates to have the next convention in Atlanta. [4] [2] Howard and her sisters funded the convention in Atlanta. [1] After the Atlanta convention in 1895, Susan B. Anthony came to visit Columbus and the Howard sisters at Sherwood Hall. [2]

Howard took the civil service exam in 1897 and became the first woman to serve as a public employee in Columbus, Georgia. [2] She worked as a money order clerk in the post office until 1900, where she may have been forced out because her brothers didn't want her working. [2] Howard went on to volunteer as vice president of GWSA in 1901. [1] In 1908, she spoke at the 1908 state suffrage convention. [1]

Howard was an outspoken atheist and was a vegetarian. [7] She became an embarrassment to the more conservative members of her family and her brothers eventually cut off money to Howard. [7]

In 1920, Howard apparently accidentally shot a boy trespassing on Sherwood Hall and the boy was hospitalized and eventually recovered. [2] However, Howard was charged for intent to murder. [2] Howard's attorney was Viola Ross Napier, one of the first women to practice law in Georgia. [1] Nevertheless, Howard was sentenced to prison for a term of one to two years. [2] Howard's brothers fought to have her sentence commuted and Governor Thomas Hardwick pardoned Howard on December 2, 1921. [2] Soon after, Howard moved to New York City. [2]

Howard died on June 10, 1934, in New York City. [1] Her body was buried in her home town of Columbus, Georgia at Linwood Cemetery. [7] Her tombstone, erected by friends, reads "Altruist, Artist, Philosopher, and Philanthropist" under her name and "MARTYRED" in very large letters at the bottom. [3] [7]

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Ida Augusta Craft was an American suffragist known for her participation in suffrage hikes.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

The Georgia Woman Suffrage Association was the first women's suffrage organization in the U.S. state of Georgia. It was founded in 1890 by Helen Augusta Howard (1865-1934). It was affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Helen Morris Lewis was an American suffragist based in North Carolina. She was the first woman in North Carolina to seek elected office, when she ran for a municipal office in Asheville in 1899.

Adella Hunt Logan was an African-American writer, educator, administrator and suffragist. Born during the Civil War, she earned her teaching credentials at Atlanta University, an historically black college founded by the American Missionary Association. She became a teacher at the Tuskegee Institute and became an activist for education and suffrage for women of color. As part of her advocacy, she published articles in some of the most noted black periodicals of her time.

Emma Maddox Funck was an American suffragist and served as president of the Maryland Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA).

Women's suffrage in Texas was a long term fight starting in 1868 at the first Texas Constitutional Convention. In both Constitutional Conventions and subsequent legislative sessions, efforts to provide women the right to vote were introduced, only to be defeated. Early Texas suffragists such as Martha Goodwin Tunstall and Mariana Thompson Folsom worked with national suffrage groups in the 1870s and 1880s. It wasn't until 1893 and the creation of the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston that Texas had a statewide women's suffrage organization. Members of TERA lobbied politicians and political party conventions on women's suffrage. Due to an eventual lack of interest and funding, TERA was inactive by 1898. In 1903, women's suffrage organizing was revived by Annette Finnigan and her sisters. These women created the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in Houston in 1903. TESA sponsored women's suffrage speakers and testified on women's suffrage in front of the Texas Legislature. In 1908 and 1912, speaking tours by Anna Howard Shaw helped further renew interest in women's suffrage in Texas. TESA grew in size and suffragists organized more public events, including Suffrage Day at the Texas State Fair. By 1915, more and more women in Texas were supporting women's suffrage. The Texas Federation of Women's Clubs officially supported women's suffrage in 1915. Also that year, anti-suffrage opponents started to speak out against women's suffrage and in 1916, organized the Texas Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (TAOWS). TESA, under the political leadership of Minnie Fisher Cunningham and with the support of Governor William P. Hobby, suffragists began to make further gains in achieving their goals. In 1918, women achieved the right to vote in Texas primary elections. During the registration drive, 386,000 Texas women signed up during a 17-day period. An attempt to modify the Texas Constitution by voter referendum failed in May 1919, but in June 1919, the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. Texas became the ninth state and the first Southern state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 28, 1919. This allowed white women to vote, but African American women still had trouble voting, with many turned away, depending on their communities. In 1923, Texas created white primaries, excluding all Black people from voting in the primary elections. The white primaries were overturned in 1944 and in 1964, Texas's poll tax was abolished. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed, promising that all people in Texas had the right to vote, regardless of race or gender.

Katherine Reed Balentine was an American suffragist and the founder of The Yellow Ribbon, a suffrage magazine.

Women's suffrage in Ohio was an ongoing fight with some small victories along the way. Women's rights issues in Ohio were put into the public eye in the early 1850s. Women inspired by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention created newspapers and then set up their own conventions, including the 1850 Ohio Women's Rights Convention which was the first women's right's convention outside of New York and the first that was planned and run solely by women. These early efforts towards women's suffrage affected people in other states and helped energize the women's suffrage movement in Ohio. Women's rights groups formed throughout the state, with the Ohio Women's Rights Association (OWRA) founded in 1853. Other local women's suffrage groups are formed in the late 1860s. In 1894, women won the right to vote in school board elections in Ohio. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was headquartered for a time in Warren, Ohio. Two efforts to vote on a constitutional amendment, one in 1912 and the other 1914 were unsuccessful, but drew national attention to women's suffrage. In 1916, women in East Cleveland gained the right to vote in municipal elections. A year later, women in Lakewood, Ohio and Columbus were given the right to vote in municipal elections. Also in 1917, the Reynolds Bill, which would allow women to vote in the next presidential election was passed, and then quickly repealed by a voter referendum sponsored by special-interest groups. On June 16, 1919, Ohio became the fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Women's suffrage in Georgia received a slow start, with the first women's suffrage group, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA) formed in 1892 by Helen Augusta Howard. Over time, the group, which focused on "taxation without representation" grew and earned the support of both men and women. Howard convinced the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold their first convention outside of Washington, D.C., in 1895. The convention, held in Atlanta, was the first large women's rights gathering in the Southern United States. GWSA continued to hold conventions and raise awareness over the next years. Suffragists in Georgia agitated for suffrage amendments, for political parties to support white women's suffrage and for municipal suffrage. In the 1910s, more organizations were formed in Georgia and the number of suffragists grew. In addition, the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage also formed an organized anti-suffrage campaign. Suffragists participated in parades, supported bills in the legislature and helped in the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women earned the right to vote in primary elections in Waycross, Georgia and in Atlanta respectively. In 1919, after the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, women still had to wait to vote because of rules regarding voter registration. White Georgia women would vote statewide in 1922. Native American women and African-American women had to wait longer to vote. Black women were actively excluded from the women's suffrage movement in the state and had their own organizations. Despite their work to vote, Black women faced discrimination at the polls in many different forms. Georgia finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Georgia. Women's suffrage in Georgia started in earnest with the formation of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA) in 1892. GWSA helped bring the first large women's rights convention to the South in 1895 when the National American Woman's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) held their convention in Atlanta. GWSA was the main source of activism behind women's suffrage until 1913. In that year, several other groups formed including the Georgia Young People's Suffrage Association (GYPSA) and the Georgia Men's League for Woman Suffrage. In 1914, the Georgia Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage (GAOWS) was formed by anti-suffragists. Despite the hard work by suffragists in Georgia, the state continued to reject most efforts to pass equal suffrage. In 1917, Waycross, Georgia allowed women to vote in primary elections and in 1919 Atlanta granted the same. Georgia was the first state to reject the Nineteenth Amendment. Women in Georgia still had to wait to vote statewide after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified on August 26, 1920. Native American and African American women had to wait even longer to vote. Georgia ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in 1970.

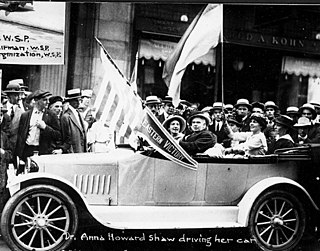

Eastern Victory was a Saxon Motor Car Company roadster purchased for Anna Howard Shaw in 1915. It was bright yellow and named "Eastern Victory" by Shaw. Shortly after the car was given to Shaw, it was seized to pay for Shaw's unpaid taxes. The car would be auctioned to pay for the taxes. At the auction, suffragists from Delaware County, Pennsylvania purchased the car. The car made appearances in New Jersey and Georgia suffrage events.

Women's suffrage in Delaware began in the late 1860s, with efforts from suffragist, Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, and an 1869 women's rights convention held in Wilmington, Delaware. Stuart, along with prominent national suffragists lobbied the Delaware General Assembly to amend the state constitution in favor of women's suffrage. Several suffrage groups were formed early on, but the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) formed in 1896, would become one of the major state suffrage clubs. Suffragists held conventions, continued to lobby the government and grow their movement. In 1913, a chapter of the Congressional Union (CU), which would later be known at the National Women's Party (NWP), was set up by Mabel Vernon in Delaware. NWP advocated more militant tactics to agitate for women's suffrage. These included picketing and setting watchfires. The Silent Sentinels protested in Washington, D.C., and were arrested for "blocking traffic." Sixteen women from Delaware, including Annie Arniel and Florence Bayard Hilles, were among those who were arrested. During World War I, both African-American and white suffragists in Delaware aided the war effort. During the ratification process for the Nineteenth Amendment, Delaware was in the position to become the final state needed to complete ratification. A huge effort went into persuading the General Assembly to support the amendment. Suffragists and anti-suffragists alike campaigned in Dover, Delaware for their cause. However, Delaware did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until March 6, 1923, well after it was already part of the United States Constitution.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Maine. Suffragists began campaigning in Maine in the mid 1850s. A lecture series was started by Ann F. Jarvis Greely and other women in Ellsworth, Maine in 1857. The first women's suffrage petition to the Maine Legislature was sent that same year. Women continue to fight for equal suffrage throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The Maine Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) is established in 1873 and the next year, the first Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) chapter was started. In 1887, the Maine Legislature votes on a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution, but it does not receive the necessary two-thirds vote. Additional attempts to pass women's suffrage legislation receives similar treatment throughout the rest of the century. In the twentieth century, suffragists continue to organize and meet. Several suffrage groups form, including the Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League in 1914 and the Men's Equal Suffrage League of Maine in 1914. In 1917, a voter referendum on women's suffrage is scheduled for September 10, but fails at the polls. On November 5, 1919 Maine ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment. On September 13, 1920, most women in Maine are able to vote. Native Americans in Maine are barred from voting for many years. In 1924, Native Americans became American citizens. In 1954, a voter referendum for Native American voting rights passes. The next year, Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot), is the Native American living on an Indian reservation to cast a vote.

While women's suffrage in Maine had an early start, dating back to the 1850s, it was a long, slow road to equal suffrage. Early suffragists brought speakers Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone to the state in the mid-1850s. Ann F. Jarvis Greely and other women in Ellsworth, Maine, created a women's rights lecture series in 1857. The first women's suffrage petition to the Maine Legislature was also sent that year. Working-class women began marching for women's suffrage in the 1860s. The Snow sisters created the first Maine women's suffrage organization, the Equal Rights Association of Rockland, in 1868. In the 1870s, a state suffrage organization, the Maine Women's Suffrage Association (MWSA), was formed. Many petitions for women's suffrage were sent to the state legislature. MWSA and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) of Maine worked closely together on suffrage issues. By the late 1880s the state legislature was considering several women's suffrage bills. While women's suffrage did not pass, during the 1890s many women's rights laws were secured. During the 1900s, suffragists in Maine continued to campaign and lecture on women's suffrage. Several suffrage organizations including a Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League and the Men's Equal Rights League were formed in the 1910s. Florence Brooks Whitehouse started the Maine chapter of the National Woman's Party (NWP) in 1915. Suffragists and other clubwomen worked together on a large campaign for a 1917 voter referendum on women's suffrage. Despite the efforts of women around the state, women's suffrage failed. Going into the next few years, a women's suffrage referendum on voting in presidential elections was placed on the September 13, 1920 ballot. But before that vote, Maine ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on November 5, 1920. It was the nineteenth state to ratify. A few weeks after ratification, MWSA dissolved and formed the League of Women Voters (LWV) of Maine. White women first voted in Maine on September 13, 1920. Native Americans in Maine had to wait longer to vote. In 1924, they became citizens of the United States. However, Maine would not allow individuals living on Indian reservations to vote. It was not until the passage of a 1954 equal rights referendum that Native Americans gained the right to vote in Maine. In 1955 Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot) was the first Native American living on a reservation in Maine to cast a vote.

Annie Louise Hall was an American suffragist and saleswoman. Hall worked as a teacher for many years, but after her experiences at a settlement house in New York City, she turned to suffrage work. Hall had experience working for women's suffrage in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. After her women's suffrage work, she went on to work as a saleswoman and eventually retired with her life partner to Ojai, California.

Mary Latimer McLendon was an activist in the prohibition and women's suffrage movements in the U.S. state of Georgia.

Frances Ellen Burr was an American suffragist and writer from Connecticut.