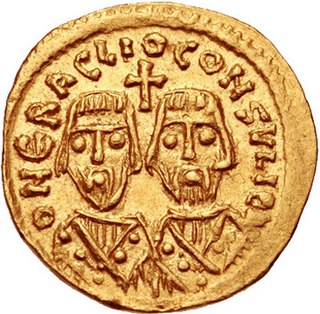

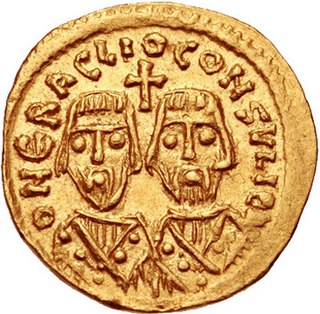

Heraclius was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular usurper Phocas.

Year 608 (DCVIII) was a leap year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 608 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Phocas was Byzantine emperor from 602 to 610. Initially, a middle-ranking officer in the Eastern Roman army, Phocas rose to prominence as a spokesman for dissatisfied soldiers in their disputes with the court of the Emperor Maurice. When the army revolted in 602, Phocas emerged as the natural leader of the mutiny. The revolt proved to be successful and led to the capture of Constantinople and the overthrow of Maurice on 23 November 602 with Phocas declaring himself emperor on the same day.

The Battle of Nineveh was the climactic battle of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.

Shahrbaraz, was shah (king) of the Sasanian Empire from 27 April 630 to 9 June 630. He usurped the throne from Ardashir III, and was killed by Iranian nobles after forty days. Before usurping the Sasanian throne he was a spahbed (general) under Khosrow II (590–628). He is furthermore noted for his important role during the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, and the events that followed afterwards.

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in 591 and survived until the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in the late 7th century. It was, along with the Exarchate of Ravenna, one of two exarchates established following the western reconquests under Emperor Justinian I to administer the territories more effectively.

Eudokia or Eudocia, originally named Fabia, was a Greek woman who became Byzantine empress as the first wife of Heraclius from 610 to her death. She was a daughter of Rogas, a landowner in the Exarchate of Africa, according to Theophanes the Confessor.

Heraclius the Elder was a Byzantine general and the father of Byzantine emperor Heraclius. Generally considered to be of Armenian origin, Heraclius the Elder distinguished himself in the war against the Sassanid Persians in the 580s. As a subordinate general, Heraclius served under the command of Philippicus during the Battle of Solachon and possibly served under Comentiolus during the Battle of Sisarbanon. Circa 595, Heraclius the Elder is mentioned as a magister militum per Armeniam sent by Emperor Maurice to quell an Armenian rebellion led by Samuel Vahewuni and Atat Khorkhoruni. Circa 600, he was appointed as the Exarch of Africa and in 608, he rebelled with his son against the usurper Phocas. Using North Africa as a base, the younger Heraclius managed to overthrow Phocas, beginning the Heraclian dynasty, which would rule Byzantium for a century. Heraclius the Elder died soon after receiving news of his son's accession to the Byzantine throne.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the dynasty of Heraclius between 610 and 711. The Heraclians presided over a period of cataclysmic events that were a watershed in the history of the Empire and the world. Heraclius, the founder of his dynasty, was of Armenian and Cappadocian (Greek) origin. At the beginning of the dynasty, the Empire's culture was still essentially Ancient Roman, dominating the Mediterranean and harbouring a prosperous Late Antique urban civilization. This world was shattered by successive invasions, which resulted in extensive territorial losses, financial collapse and plagues that depopulated the cities, while religious controversies and rebellions further weakened the Empire.

The siege of Constantinople in 626 by the Sassanid Persians and Avars, aided by large numbers of allied Slavs and Bulgars ended in a strategic victory for the Byzantines. The failure of the siege saved the empire from collapse, and, combined with other victories achieved by Emperor Heraclius the previous year and in 627, enabled Byzantium to regain its territories and end the destructive Roman–Persian Wars by enforcing a treaty with borders status quo c. 590.

Gregoria was the Byzantine empress as the wife of Constantine III. She participated in the minority regency government of her son, Constans II, in 641–650.

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 was the final and most devastating of the series of wars fought between the Byzantine / Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Iran. The previous war between the two powers had ended in 591 after Emperor Maurice helped the Sasanian king Khosrow II regain his throne. In 602 Maurice was murdered by his political rival Phocas. Khosrow declared war, ostensibly to avenge the death of the deposed emperor Maurice. This became a decades-long conflict, the longest war in the series, and was fought throughout the Middle East: in Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Armenia, the Aegean Sea and before the walls of Constantinople itself.

Nicetas or Niketas was the cousin of Emperor Heraclius. He played a major role in the revolt against Phocas that brought Heraclius to the throne, where he captured Egypt for his cousin. Nicetas remained governor of Egypt thereafter, and participated also in the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628, but failed to stop the Sassanid conquest of Egypt ca. 618/619. He disappears from the sources thereafter, but possibly served as Exarch of Africa until his death.

Priscus or Priskos was a leading Eastern Roman general during the reigns of the Byzantine emperors Maurice, Phocas and Heraclius. Priscus comes across as an effective and capable military leader, although the contemporary sources are markedly biased in his favour. Under Maurice, he distinguished himself in the campaigns against the Avars and their Slavic allies in the Balkans. Absent from the capital at the time of Maurice's overthrow and murder by Phocas, he was one of the few of Maurice's senior aides who were able to survive unharmed into the new regime, remaining in high office and even marrying the new emperor's daughter. Priscus, however, also negotiated with and assisted Heraclius in the overthrow of Phocas, and was entrusted with command against the Persians in 611–612. After the failure of this campaign, he was dismissed and tonsured. He died shortly after.

Comentiolus was the brother of the Eastern Roman emperor Phocas.

Domentziolus or Domnitziolus was a nephew of the Byzantine emperor Phocas, appointed curopalates and general in the East during his uncle's reign. He was one of the senior Byzantine military leaders during the opening stages of the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. His defeats opened the way for the fall of Mesopotamia and Armenia and the invasion of Anatolia by the Persians. In 610, Phocas was overthrown by Heraclius, and Domentziolus was captured but escaped serious harm.

Theodore was the brother of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, a curopalates and leading general in Heraclius' wars against the Persians and against the Muslim conquest of the Levant.

Saint Theodore of Sykeon, also known as Theodore the Sykeote, was a revered Byzantine ascetic, who lived between the first half of the 6th century and the thirteenth year of the Emperor Heraclius' rule in the early 7th century. His hagiography, written after 641, is a key primary source for the reign of Emperor Heraclius. His feast day is 22 April.

David was one of three co-emperors of Byzantium for a few months in late 641, and had the regnal name Tiberius. David was the son of Emperor Heraclius and his wife and niece Empress Martina. He was born after the emperor and empress had visited Jerusalem and his given name reflects a deliberate attempt to link the imperial family with the Biblical David. The David Plates, which depict the life of King David, may likewise have been created for the young prince or to commemorate his birth. David was given the senior court title caesar in 638, in a ceremony during which he received the kamelaukion cap previously worn by his older brother Heraclonas.