The history of medicine is both a study of medicine throughout history as well as a multidisciplinary field of study that seeks to explore and understand medical practices, both past and present, throughout human societies.

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness. Contemporary medicine applies biomedical sciences, biomedical research, genetics, and medical technology to diagnose, treat, and prevent injury and disease, typically through pharmaceuticals or surgery, but also through therapies as diverse as psychotherapy, external splints and traction, medical devices, biologics, and ionizing radiation, amongst others.

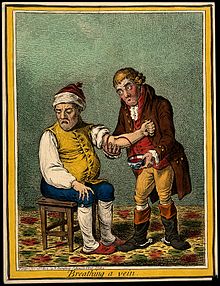

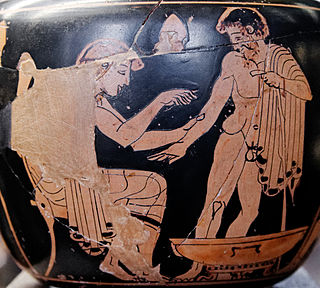

Bloodletting is the withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily fluids were regarded as "humours" that had to remain in proper balance to maintain health. It is claimed to have been the most common medical practice performed by surgeons from antiquity until the late 19th century, a span of over 2,000 years. In Europe, the practice continued to be relatively common until the end of the 19th century. The practice has now been abandoned by modern-style medicine for all except a few very specific medical conditions. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the historical use of bloodletting was harmful to patients.

Osteopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine that emphasizes physical manipulation of the body's muscle tissue and bones. In most countries, practitioners of osteopathy are not medically trained and are referred to as osteopaths.

Benjamin Rush was an American revolutionary, a Founding Father of the United States and signatory to the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educator, and the founder of Dickinson College. Rush was a Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress. He later described his efforts in support of the American Revolution, saying: "He aimed right." He served as surgeon general of the Continental Army and became a professor of chemistry, medical theory, and clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania.

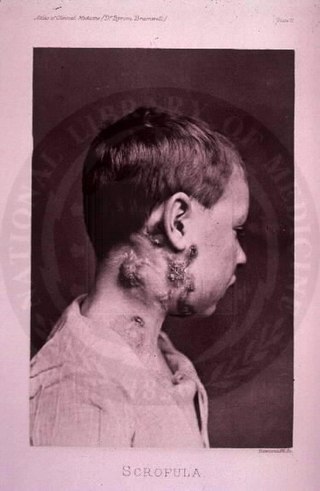

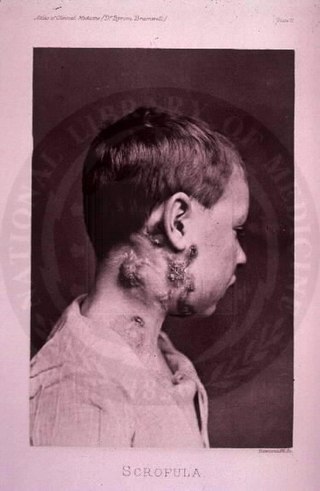

The disease mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis, also known as scrofula and historically as king's evil, involves a lymphadenitis of the cervical lymph nodes associated with tuberculosis as well as nontuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria.

Allopathic medicine, or allopathy, is an archaic and derogatory label originally used by 19th-century homeopaths to describe heroic medicine, the precursor of modern evidence-based medicine. There are regional variations in usage of the term. In the United States, the term is sometimes used to contrast with osteopathic medicine, especially in the field of medical education. In India, the term is used to distinguish conventional modern medicine from Siddha medicine, Ayurveda, homeopathy, Unani and other alternative and traditional medicine traditions, especially when comparing treatments and drugs.

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

In the Middle Ages, the medicine of Western Europe was composed of a mixture of existing ideas from antiquity. In the Early Middle Ages, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, standard medical knowledge was based chiefly upon surviving Greek and Roman texts, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere. Medieval medicine is widely misunderstood, thought of as a uniform attitude composed of placing hopes in the church and God to heal all sicknesses, while sickness itself exists as a product of destiny, sin, and astral influences as physical causes. On the other hand, medieval medicine, especially in the second half of the medieval period, became a formal body of theoretical knowledge and was institutionalized in the universities. Medieval medicine attributed illnesses, and disease, not to sinful behavior, but to natural causes, and sin was connected to illness only in a more general sense of the view that disease manifested in humanity as a result of its fallen state from God. Medieval medicine also recognized that illnesses spread from person to person, that certain lifestyles may cause ill health, and some people have a greater predisposition towards bad health than others.

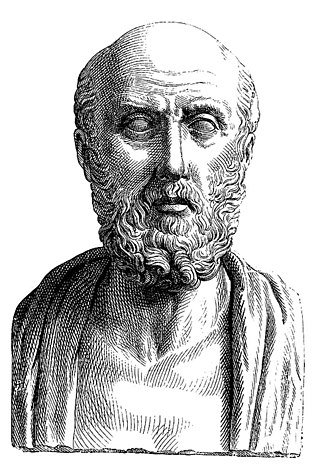

The treatise On Ancient Medicine is perhaps the most intriguing and compelling work of the Hippocratic Corpus. The Corpus itself is a collection of about sixty writings covering all areas of medical thought and practice. Traditionally associated with Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, philological evidence now suggests that it was written over a period of several centuries and stylistically seems to indicate that it was the product of many authors dating from about 450–400 B.C.

Mercury(I) chloride is the chemical compound with the formula Hg2Cl2. Also known as the mineral calomel (a rare mineral) or mercurous chloride, this dense white or yellowish-white, odorless solid is the principal example of a mercury(I) compound. It is a component of reference electrodes in electrochemistry.

Calomel is a mercury chloride mineral with formula Hg2Cl2 (see mercury(I) chloride). The name derives from Greek kalos (beautiful) and melas (black) because it turns black on reaction with ammonia. This was known to alchemists.

In the history of medicine, "Islamic medicine" Also known as "Arabian medicine" is the science of medicine developed in the Middle East, and usually written in Arabic, the lingua franca of Islamic civilization.

Empiric therapy or empirical therapy is medical treatment or therapy based on experience and, more specifically, therapy begun on the basis of a clinical "educated guess" in the absence of complete or perfect information. Thus it is applied before the confirmation of a definitive medical diagnosis or without complete understanding of an etiology, whether the biological mechanism of pathogenesis or the therapeutic mechanism of action. The name shares the same stem with empirical evidence, involving an idea of practical experience.

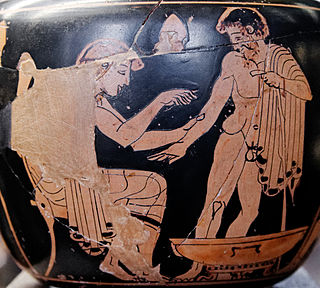

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. The Greek term for medicine was iatrikē. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset. Early on the ancient Greeks believed that illnesses were "divine punishments" and that healing was a "gift from the Gods". As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.

Therapeutic nihilism is a contention that it is impossible to cure people or societies of their ills through treatment.

Medicine in ancient Rome was highly influenced by ancient Greek medicine, but also developed new practices through knowledge of the Hippocratic Corpus combined with use of the treatment of diet, regimen, along with surgical procedures. This was most notably seen through the works of two of the prominent Greek physicians, Dioscorides and Galen, who practiced medicine and recorded their discoveries. This is contrary to two other physicians like Soranus of Ephesus and Asclepiades of Bithynia, who practiced medicine both in outside territories and in ancient Roman territory, subsequently. Dioscorides was a Roman army physician, Soranus was a representative for the Methodic school of medicine, Galen performed public demonstrations, and Asclepiades was a leading Roman physician. These four physicians all had knowledge of medicine, ailments, and treatments that were healing, long lasting and influential to human history.

Islamic psychology or ʿilm al-nafs, the science of the nafs, is the medical and philosophical study of the psyche from an Islamic perspective and addresses topics in psychology, neuroscience, philosophy of mind, and psychiatry as well as psychosomatic medicine. In Islam, mental health and mental illness were viewed with a holistic approach. This approach emphasized the mutual connection between maintaining adequate mental wellbeing and good physical health in an individual. People who practice Islam thought it was necessary to maintain positive mental health in order to partake in prayer and other religious obligations.

Domestic medicine or domestic health care is the behavioral, nutritional and health care practices, hygiene included, performed in the household and transmitted from one generation to the other.

Jacqueline Felice de Almania, was reportedly from Florence, Italy. She was an early 14th-century French physician in Paris, France who was placed on trial in 1322 for unlawful practice.