Geomancy translates literally to "earth divination," and the term is used for methods of divination that interpret geographic features, markings on the ground, or the patterns formed by soil, rocks, or sand.

Indian architecture is rooted in the history, culture, and religion of India. Among several architectural styles and traditions, the best-known include the many varieties of Hindu temple architecture and Indo-Islamic architecture, especially Rajput architecture, Mughal architecture, South Indian architecture, and Indo-Saracenic architecture. Early Indian architecture was made from wood, which did not survive due to rotting and instability in the structures. Instead, the earliest existing architecture are made with Indian rock-cut architecture, including many Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain temples.

Vastu shastra is a traditional Indian system of architecture based on ancient texts that describe principles of design, layout, measurements, ground preparation, space arrangement, and spatial geometry. The designs aim to integrate architecture with nature, the relative functions of various parts of the structure, and ancient beliefs utilising geometric patterns (yantra), symmetry, and directional alignments.

Shastra is a Sanskrit word that means "precept, rules, manual, compendium, book or treatise" in a general sense. The word is generally used as a suffix in the Indian literature context, for technical or specialized knowledge in a defined area of practice.

In the Hindu tradition, a murti is a devotional image, such as a statue or icon, of a deity or saint used during puja and/or in other customary forms of actively expressing devotion or reverence - whether at Hindu temples or shrines. A mūrti is a symbolic icon representing Divinity for the purpose of devotional activities. Thus, not all icons of gods and saints are mūrti; for example, purely decorative depictions of Divine figures often adorn Hindu temple architecture in intricately carved doorframes, on colourfully painted walls, and ornately sculpted rooftop domes. A mūrti itself is not God, but it is merely a representative shape, symbolic embodiment, or iconic manifestation of God.

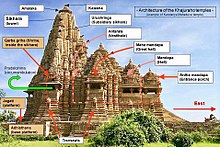

Hindu temple architecture as the main form of Hindu architecture has many varieties of style, though the basic nature of the Hindu temple remains the same, with the essential feature an inner sanctum, the garbha griha or womb-chamber, where the primary Murti or the image of a deity is housed in a simple bare cell. For rituals and prayers, this chamber frequently has an open space that can be moved in a clockwise direction. There are frequently additional buildings and structures in the vicinity of this chamber, with the largest ones covering several acres. On the exterior, the garbhagriha is crowned by a tower-like shikhara, also called the vimana in the south. The shrine building often includes an circumambulatory passage for parikrama, a mandapa congregation hall, and sometimes an antarala antechamber and porch between garbhagriha and mandapa. In addition to other small temples in the compound, there may be additional mandapas or buildings that are either connected or separate from the larger temples.

A veranda or verandah is a roofed, open-air hallway or porch, attached to the outside of a building. A veranda is often partly enclosed by a railing and frequently extends across the front and sides of the structure.

A Hindu temple is a structure designed to bring Hindus and gods together through worship, sacrifice, and devotion, thought of as the house of the god to whom it is dedicated. The symbolism and structure of a Hindu temple are rooted in Vedic traditions, deploying circles and squares. It also represents recursion and the representation of the equivalence of the macrocosm and the microcosm by astronomical numbers, and by "specific alignments related to the geography of the place and the presumed linkages of the deity and the patron". A temple incorporates all elements of the Hindu cosmos — presenting the good, the evil and the human, as well as the elements of the Hindu sense of cyclic time and the essence of life — symbolically presenting dharma, artha, kama, moksha, and karma.

Vesara is a hybrid form of Indian temple architecture, with South Indian plan and a shape that features North Indian details. This fusion style likely originated in the historic architecture schools of the Dharwad region. It is common in the surviving temples of later Chalukyas and Hoysalas in the Deccan region, particularly Karnataka. According to Indian texts, Vesara was popular in central parts of India such as between the Vindhyas and the river Krishna. It is one of six major types of Indian temple architecture found in historic texts along with Nagara, Dravida, Bhumija, Kalinga, and Varata.

Samarangana Sutradhara, sometimes referred to as Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra, is an 11th-century poetic treatise on classical Indian architecture written in Sanskrit language attributed to Paramara King Bhoja of Dhar. The title Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra is a compound word that literally means "architect of human dwellings", but can also be decomposed to an alternate meaning as "stage manager for battlefields" – possibly a play of words to recognize its royal author.

Architectural theory is the act of thinking, discussing, and writing about architecture. Architectural theory is taught in all architecture schools and is practiced by the world's leading architects. Some forms that architecture theory takes are the lecture or dialogue, the treatise or book, and the paper project or competition entry. Architectural theory is often didactic, and theorists tend to stay close to or work from within schools. It has existed in some form since antiquity, and as publishing became more common, architectural theory gained an increased richness. Books, magazines, and journals published an unprecedented number of works by architects and critics in the 20th century. As a result, styles and movements formed and dissolved much more quickly than the relatively enduring modes in earlier history. It is to be expected that the use of the internet will further the discourse on architecture in the 21st century.

Shilpa Shastras literally means the Science of Shilpa. It is an ancient umbrella term for numerous Hindu texts that describe arts, crafts, and their design rules, principles and standards. In the context of Hindu temple architecture and sculpture, Shilpa Shastras were manuals for sculpture and Hindu iconography, prescribing among other things, the proportions of a sculptured figure, composition, principles, meaning, as well as rules of architecture.

A salabhanjika or shalabhanjika is a term found in Indian art and literature with a variety of meanings. In Buddhist art, it means an image of a woman or yakshi next to, often holding, a tree, or a reference to Maya near the sala tree giving birth to Siddhartha (Buddha). In Hindu and Jain art, the meaning is less specific, and it is any statue or statuette, usually female, that breaks the monotony of a plain wall or space and thus enlivens it.

The Mānasāra, also known as Manasa or Manasara Shilpa Shastra, is an ancient Sanskrit treatise on Indian architecture and design. Organized into 70 adhyayas (chapters) and 10,000 shlokas (verses), it is one of many Hindu texts on Shilpa Shastra – science of arts and crafts – that once existed in 1st-millennium CE. The Manasara is among the few on Ancient Indian architecture whose complete manuscripts have survived into the modern age. It is a treatise that provides detailed guidelines on the building of Hindu temples, sculptures, houses, gardens, water tanks, laying out of towns and other structures.

The Kasivisvesvara temple, also referred to as the Kavatalesvara, Kashivishveshvara or Kashi Vishvanatha temple of Lakkundi is located in the Gadag district of Karnataka state, India. It is about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from Gadag city, between Hampi and Goa. The Kasivisvesvara temple is one of the best illustrations of fully developed Kalyana Chalukya style of Hindu architecture.

The Matsya Purana is one of the eighteen major Puranas (Mahapurana), and among the oldest and better preserved in the Puranic genre of Sanskrit literature in Hinduism. The text is a Vaishnavism text named after the half-human and half-fish avatar of Vishnu. However, the text has been called by the 19th-century Sanskrit scholar Horace Hayman Wilson, "although a Shaivism (Shiva-related) work, it is not exclusively so"; the text has also been referred to one that simultaneously praises various Hindu gods and goddesses.

Chaya Someswara Temple, also known as the Chaya Someshvara Swamy Alayam or the Saila-Somesvara temple, is a Saivite Hindu temple located in Panagal, Nalgonda district of Telangana, India. It was built around the mid 11th-century during the rule of the Kunduru Chodas, supported and embellished further by later Hindu dynasties of Telangana. Some date it to late 11th to early 12th-century.

A śālā (shala) is a Sanskrit term that means any "house, space, covered pavilion or enclosure" in Indian architecture. In other contexts śālā – also spelled calai or salai in South India – means a feeding house or a college of higher studies linked to a Hindu or Jain temple and supported by local population and wealthy patrons. In the early Buddhist literature of India, śālā means a "hut, cell, hall, pavilion or shed" as in Vedic śālā, Aggiśālā, Paniyaśālā.

The Aparajitaprccha is a 12th-century Sanskrit text of Bhuvanadeva with major sections on architecture and arts (Kala). Predominantly a Hindu text, it largely reflects the north and western Indian traditions. The text also includes chapters on Jain architecture and arts. The text is notable for its sections on temple architecture (vastu), sculpture (shilpa), painting (chitra) and classical music and dance.

In several ancient Indian texts, Nagnajit appears as the name of a king or kings who ruled Gandhara and/or neighbouring areas. Some texts also refer to Nagnajit as an authority on temple architecture or medicine. According to one theory, all these references are to a single person; another theory identifies them as distinct persons.