Related Research Articles

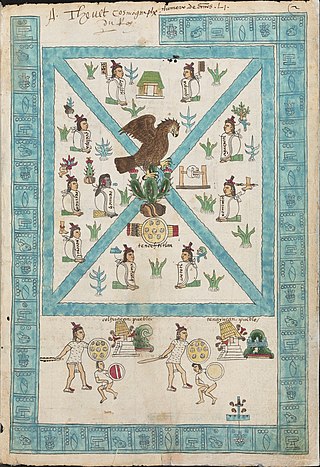

The codex was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term codex is often used for ancient manuscript books, with handwritten contents. A codex, much like the modern book, is bound by stacking the pages and securing one set of edges by a variety of methods over the centuries, yet in a form analogous to modern bookbinding. Modern books are divided into paperback and those bound with stiff boards, called hardbacks. Elaborate historical bindings are called treasure bindings. At least in the Western world, the main alternative to the paged codex format for a long document was the continuous scroll, which was the dominant form of document in the ancient world. Some codices are continuously folded like a concertina, in particular the Maya codices and Aztec codices, which are actually long sheets of paper or animal skin folded into pages.

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves," or at Tamoanchan.

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

Maya codices are folding books written by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization in Maya hieroglyphic script on Mesoamerican bark paper. The folding books are the products of professional scribes working under the patronage of deities such as the Tonsured Maize God and the Howler Monkey Gods. Most of the codices were destroyed by conquistadors and Catholic priests in the 16th century. The codices have been named for the cities where they eventually settled. The Dresden codex is generally considered the most important of the few that survive.

The Dresden Codex is a Maya book, which was believed to be the oldest surviving book written in the Americas, dating to the 11th or 12th century. However, in September 2018 it was proven that the Maya Codex of Mexico, previously known as the Grolier Codex, is, in fact, older by about a century. The codex was rediscovered in the city of Dresden, Germany, hence the book's present name. It is located in the museum of the Saxon State Library. The codex contains information relating to astronomical and astrological tables, religious references, seasons of the earth, and illness and medicine. It also includes information about conjunctions of planets and moons.

Aztec codices are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.

The Codex Borbonicus is an Aztec codex written by Aztec priests shortly before or after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It is named after the Palais Bourbon in France and kept at the Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée Nationale in Paris. The codex is an outstanding example of how Aztec manuscript painting is crucial for the understanding of Mexica calendric constructions, deities, and ritual actions.

Mesoamerica, along with Mesopotamia and China, is one of three known places in the world where writing is thought to have developed independently. Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are a combination of logographic and syllabic systems. They are often called hieroglyphs due to the iconic shapes of many of the glyphs, a pattern superficially similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs. Fifteen distinct writing systems have been identified in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, many from a single inscription. The limits of archaeological dating methods make it difficult to establish which was the earliest and hence the progenitor from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and the most widely known, is the classic Maya script. Earlier scripts with poorer and varying levels of decipherment include the Olmec hieroglyphs, the Zapotec script, and the Isthmian script, all of which date back to the 1st millennium BC. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved, partly in indigenous scripts and partly in postconquest transcriptions in the Latin script.

The traditions of indigenous Mesoamerican literature extend back to the oldest-attested forms of early writing in the Mesoamerican region, which date from around the mid-1st millennium BCE. Many of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica are known to have been literate societies, who produced a number of Mesoamerican writing systems of varying degrees of complexity and completeness. Mesoamerican writing systems arose independently from other writing systems in the world, and their development represents one of the very few such origins in the history of writing.

The Feathered Serpent is a prominent supernatural entity or deity, found in many Mesoamerican religions. It is still called Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs, Kukulkan among the Yucatec Maya, and Q'uq'umatz and Tohil among the K'iche' Maya.

A writing material is a surface that can be written on with suitable instruments, or used for symbolic or representational drawings. Building material on which writings or drawings are produced are not included. The gross characterization of writing materials is by the material constituting the writing surface and the number, size, and usage and storage configuration of multiple surfaces into a single object. Writing materials are often paired with specific types of writing instruments. Other important attributes of a writing material are its reusability, its permanence, and its resistance to fraudulent misuse.

Antiquities of Mexico is a compilation of facsimile reproductions of Mesoamerican literature such as Maya codices, Mixtec codices, and Aztec codices as well as historical accounts and explorers' descriptions of archaeological ruins. It was assembled and published by Edward King, Lord Kingsborough, in the early decades of the 19th century. While much of the material pertains to pre-Columbian cultures, there are also documents relevant to studies of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Antiquities of Mexico was produced to make copies of rare manuscripts in European collections available for study by scholars.

The Abbey Library of Saint Gall is a significant medieval monastic library located in St. Gallen, Switzerland. In 1983, the library, as well as the Abbey of St. Gall, were designated a World Heritage Site, as "an outstanding example of a large Carolingian monastery and was, since the 8th century until its secularisation in 1805, one of the most important cultural centres in Europe".

Library history is a subdiscipline within library science and library and information science focusing on the history of libraries and their role in societies and cultures. Some see the field as a subset of information history. Library history is an academic discipline and should not be confused with its object of study : the discipline is much younger than the libraries it studies. Library history begins in ancient societies through contemporary issues facing libraries today. Topics include recording mediums, cataloguing systems, scholars, scribes, library supporters and librarians.

The Maya Codex of Mexico (MCM) is a Maya screenfold codex manuscript of a pre-Columbian type. Long known as the Grolier Codex or Sáenz Codex, in 2018 it was officially renamed the Códice Maya de México (CMM) by the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico. It is one of only four known extant Maya codices, and the only one that still resides in the Americas.

Sophie Dobzhansky Coe was an anthropologist, food historian, and author, who studied the history of chocolate.

Božidar Ljubavić, better known as Božidar Goraždanin, was founder of the Goražde printing house, the second Serbian language printing house and one of the earliest printing houses on the Balkans. Since 25 October 1519 he printed books on Cyrillic alphabet, first in Venice and then in the Church of Saint George in Sopotnica, Sanjak of Herzegovina, Ottoman Empire in period 1519–23. Only four printing presses were operational during the entire Ottoman period in Bosnia. The first press was press of Božidar Goraždanin while other three presses existed only in the 19th century. In 1523 his printing house became nonoperational.

As of 2018, ten firms in Germany rank among the world's biggest publishers of books in terms of revenue: C.H. Beck, Bertelsmann, Cornelsen Verlag, Haufe-Gruppe, Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, Ernst Klett Verlag, Springer Nature, Thieme, WEKA Holding, and Westermann Druck- und Verlagsgruppe. Overall, "Germany has some 2,000 publishing houses, and more than 90,000 titles reach the public each year, a production surpassed only by the United States." Unlike many other countries, "book publishing is not centered in a single city but is concentrated fairly evenly in Berlin, Hamburg, and the regional metropolises of Cologne, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and Munich."

As of 2018, Wolters Kluwer ranks as the Dutch biggest publisher of books in terms of revenue. Other notable Dutch houses include Brill and Elsevier.

The Oxford Companion to the Book is a comprehensive reference work that covers the history and production of books from ancient to modern times. It is edited by Michael F. Suarez, SJ, and H. R. Woudhuysen, and published by Oxford University Press.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Roldan Vera, Eugenia (2013). "The History of the Book in Latin America (Including Incas and Aztecs)". In Suarez, Michael; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Book: A Global History (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 656. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- ↑ Roldan Vera, Eugenia (2013). "The History of the Book in Latin America (Including Incas and Aztecs)". In Suarez, Michael; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Book: A Global History (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 656–670. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roldan Vera, Eugenia (2013). "The History of the Book in Latin America (Including Incas and Aztecs)". In Suarez, Michael; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Book: A Global History (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 657. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- ↑ Phillips, Charles (2017). The illustrated encyclopedia of Aztec & Maya: the greatest civilizations of ancient Central America with 1000 photographs, paintings & maps. Jones, David M. London. p. 486. ISBN 978-1-78214-340-6. OCLC 1005933447.

- ↑ Fischer, Steven R. (2001). History of writing. London: Reaktion Books. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-86189-588-2. OCLC 438712074.

- 1 2 3 Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books : a living history. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-500-29115-3. OCLC 857089276.

- ↑ "Cortés and the Aztecs - Exploring the Early Americas | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ↑ "Basic Aztec facts: AZTEC BOOKS". www.mexicolore.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Murray, Stuart, 1948- (2009). The library : an illustrated history. New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4. OCLC 277203534.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Collections, Special. "Tarlton Law Library: Exhibit - Aztec and Maya Law: Aztec Legal System and Sources of Law". tarlton.law.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2013). Books : A Living History. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-500-29115-3. OCLC 857089276.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4.

- 1 2 Roldan Vera, Eugenia (2013). "The History of the Book in Latin America (Including Incas and Aztecs)". In Suarez, Michael; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Book: A Global History (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 660. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- 1 2 Murray, Stuart (2009). Library: An Illustrated History. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 136.

- 1 2 Roldan Vera, Eugenia (2013). "The History of the Book in Latin America (Including Incas and Aztecs)". In Suarez, Michael; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Book: A Global History (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 661. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- ↑ "Biblioteca Palafoxiana" (PDF). UNESCO Biblioteca Palafoxiana.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). Library: An Illustrated History. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 9781616084530.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History (1st ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History (1st ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- ↑ Roldan Vera, Eugenia (2013). "The History of the Book in Latin America (Including Incas and Aztecs)". In Suarez, Michael; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Book: A Global History (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 659. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History (1st ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History (1st ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History (1st ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.