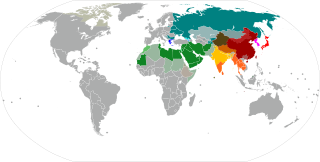

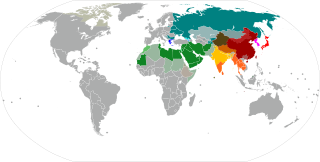

A bidirectional text contains two text directionalities, right-to-left (RTL) and left-to-right (LTR). It generally involves text containing different types of alphabets, but may also refer to boustrophedon, which is changing text direction in each row.

Furigana is a Japanese reading aid consisting of smaller kana printed either above or next to kanji or other characters to indicate their pronunciation. It is one type of ruby text. Furigana is also known as yomigana (読み仮名) and rubi in Japanese. In modern Japanese, it is usually used to gloss rare kanji, to clarify rare, nonstandard or ambiguous kanji readings, or in children's or learners' materials. Before the post-World War II script reforms, it was more widespread.

Katakana is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana, kanji and in some cases the Latin script.

Punctuation marks are marks indicating how a piece of written text should be read and, consequently, understood. The oldest known examples of punctuation marks were found in the Mesha Stele from the 9th century BC, consisting of points between the words and horizontal strokes between sections. The alphabet-based writing began with no spaces, no capitalization, no vowels, and with only a few punctuation marks, as it was mostly aimed at recording business transactions. Only with the Greek playwrights did the ends of sentences begin to be marked to help actors know when to make a pause during performances. Punctuation includes space between words and the other, historically or currently used, signs.

Sutton SignWriting, or simply SignWriting, is a system of writing sign languages. It is highly featural and visually iconic, both in the shapes of the characters, which are abstract pictures of the hands, face, and body, and in their spatial arrangement on the page, which does not follow a sequential order like the letters that make up written English words. It was developed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton, a dancer who had, two years earlier, developed DanceWriting. Some newer standardized forms are known as the International Sign Writing Alphabet (ISWA).

Ruby characters or rubi characters are small, annotative glosses that are usually placed above or to the right of logographic characters of languages in the East Asian cultural sphere, such as Chinese hanzi, Japanese kanji, and Korean hanja, to show the logographs' pronunciation; these were formerly also used for Vietnamese chữ Hán and chữ Nôm, and may still occasionally be seen in that context when reading archaic texts. Typically called just ruby or rubi, such annotations are most commonly used as pronunciation guides for characters that are likely to be unfamiliar to the reader.

The Soyombo script is an abugida developed by the monk and scholar Zanabazar in 1686 to write Mongolian. It can also be used to write Tibetan and Sanskrit.

Stroke order is the order in which the strokes of a Chinese character are written. A stroke is a movement of a writing instrument on a writing surface.

Iteration marks are characters or punctuation marks that represent a duplicated character or word.

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.

Quotation marks are punctuation marks used in pairs in various writing systems to identify direct speech, a quotation, or a phrase. The pair consists of an opening quotation mark and a closing quotation mark, which may or may not be the same glyph. Quotation marks have a variety of forms in different languages and in different media.

The Klingon scripts are fictional alphabetic scripts used in the Star Trek movies and television shows to write the Klingon language.

Genkō yōshi is a type of Japanese paper used for writing. It is printed with squares, typically 200 or 400 per sheet, each square designed to accommodate a single Japanese character or punctuation mark. Genkō yōshi may be used with any type of writing instrument, and with or without a shitajiki.

Japanese punctuation includes various written marks, which differ from those found in European languages, as well as some not used in formal Japanese writing but frequently found in more casual writing, such as exclamation and question marks.

Writing systems that use Chinese characters also include various punctuation marks, derived from both Chinese and Western sources. Historically, judou annotations were often used to indicate the boundaries of sentences and clauses in text. The use of punctuation in written Chinese only became mandatory during the 20th century, due to Western influence. Unlike modern punctuation, judou marks were added by scholars for pedagogical purposes and were not viewed as integral to the text. Texts were therefore generally transmitted without judou. In most cases, this practice did not interfere with the interpretation of a text, although it occasionally resulted in ambiguity.

Siddhaṃ, also known in its later evolved form as Siddhamātṛkā, is a medieval Brahmic abugida, derived from the Gupta script and ancestral to the Nāgarī, Eastern Nagari, Tirhuta, Odia and Nepalese scripts.

Transformations of text are strategies to perform geometric transformations on text, particularly in systems that do not natively support transformation, such as HTML, seven-segment displays and plain text.

A writing system comprises a particular set of symbols, called a script, as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. Writing systems can generally be classified according to how symbols function according to these rules, with the most common types being alphabets, syllabaries, and logographies. Alphabets use symbols called letters that correspond to spoken phonemes. Abjads generally only have letters for consonants, while pure alphabets have letters for both consonants and vowels. Abugidas use characters that correspond to consonant–vowel pairs. Syllabaries use symbols called syllabograms to represent syllables or moras. Logographies use characters that represent semantic units, such as words or morphemes.

The emphasis mark or emphasis dot is a typographic marking used in some East Asian languages to indicate emphasis. The markings takes in many forms like, a dot or a bullet, a circle, or a triangle. It was used more traditionally, but nowadays, with technology, quotations or changing of font style prevails.

East Asian typography is the application of typography to the writing systems used for the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese languages. Scripts represented in East Asian typography include Chinese characters, kana, and hangul.