The Inca Empire, called Tawantinsuyu by its subjects, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilization rose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. The Spanish began the conquest of the Inca Empire in 1532 and by 1572, the last Inca state was fully conquered.

The Inca road system was the most extensive and advanced transportation system in pre-Columbian South America. It was about 40,000 kilometres (25,000 mi) long. The construction of the roads required a large expenditure of time and effort.

The Inca religion was a group of beliefs and rites that were related to a mythological system evolving from pre-Inca times to Inca Empire. Faith in the Tawantinsuyu was manifested in every aspect of his life, work, festivities, ceremonies, etc. They were polytheists and there were local, regional and pan-regional divinities.

The Huaca del Sol is an adobe brick pyramid built by the Moche civilization on the northern coast of what is now Peru. The pyramid is one of several ruins found near the volcanic peak of Cerro Blanco, in the coastal desert near Trujillo at the Moche Valley. The other major ruin at the site is the nearby Huaca de la Luna, a better-preserved but smaller temple.

The Sapa Inca was the monarch of the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu), as well as ruler of the earlier Kingdom of Cusco and the later Neo-Inca State. While the origins of the position are mythical and originate from the legendary foundation of the city of Cusco, it seems to have come into being historically around 1100 AD. Although the Inca believed the Sapa to be the son of Inti and often referred to him as Intip Churin or 'Son of the Sun,' the position eventually became hereditary, with son succeeding father. The principal wife of the Inca was known as the Coya or Qoya. The Sapa Inca was at the top of the social hierarchy, and played a dominant role in the political and spiritual realm.

Among the Inca, a panaca or panaqa was the royal lineage or family clan of each Sapa Inca, the monarch or emperor of the Inca Empire. According to the information provided by the Spanish chroniclers, the panacas were formed by all of the descendants of a Sapa Inca together with kinship groups united by matrimonial ties. The panaca excluded the auqui, the Inca's son, who would succeed in the reign because, when he became emperor, would leave his original panaca and form his own one.

Huaca de la Luna is a large adobe brick structure built mainly by the Moche people of northern Peru. Along with the Huaca del Sol, the Huaca de la Luna is part of Huacas de Moche, which is the remains of an ancient Moche capital city called Cerro Blanco, by the volcanic peak of the same name.

Coricancha, Curicancha, Koricancha, Qoricancha or Qorikancha was the most important temple in the Inca Empire, and was described by early Spanish colonialists. It is located in Cusco, Peru, which was the capital of the empire.

Capacocha or Qhapaq hucha was an important sacrificial rite among the Inca that typically involved the sacrifice of children. Children of both sexes were selected from across the Inca empire for sacrifice in capacocha ceremonies, which were performed at important shrines distributed across the empire, known as huacas, or wak'akuna.

Raqch'i (Quechua) is an Inca archaeological site in Peru located in the Cusco Region, Canchis Province, San Pedro District, near the populated place Raqch'i. It is 3480 meters above sea level and 110 kilometers from the city of Cuzco. It also known as the Temple of Wiracocha, one of its constituents. Both lie along the Vilcanota River. The site has experienced a recent increase in tourism in recent years, with 83,334 visitors to the site in 2006, up from 8,183 in 2000 and 452 in 1996.

The Lima culture was an indigenous civilization which existed in modern-day Lima, Peru during the Early Intermediate Period, extending from roughly 100 to 650. This pre-Incan culture, which overlaps with surrounding Paracas, Moche, and Nasca civilizations, was located in the desert coastal strip of Peru in the Chillon, Rimac and Lurin River valleys. It can be difficult to differentiate the Lima culture from surrounding cultures due to both its physical proximity to other, and better documented cultures, in Coastal Peru, and because it is chronologically very close, if not over lapped, by these other cultures as well. These factors all help contribute to the obscurity of the Lima culture, of which much information is still left to be learned.

Huaca de Chena, also known as the Chena Pukara, is an Inca site on Chena Mountain, in the basin of San Bernardo, at the edge of the Calera de Tango and Maipo Province communes in Chile. Tala Canta Ilabe was the last Inca who celebrated Inti Raymi in its Ushnu.

In the Inca Empire the ushnu was an altar for cults to the deities, a throne for the Sapa Inca (emperor), an elevated place for judgment and a reviewing stand of military command. In several cases the ushnu may have been used as a solar observatory. Ushnus mark the center of plazas of the Inca administrative centers all along the highland path of the Inca road system.

Q'enqo, Qenko,Kenko, or Quenco is an archaeological site in the Sacred Valley of Peru located in the Cusco Region, Cusco Province, Cusco District, about 6 km north east of Cusco. The site was declared a Cultural Heritage (Patrimonio Cultural) of the Cusco Region by the National Institute of Culture.

The Andean civilizations were South American complex societies of many indigenous people. They stretched down the spine of the Andes for 4,000 km (2,500 mi) from southern Colombia, to Ecuador and Peru, including the deserts of coastal Peru, to north Chile and northwest Argentina. Archaeologists believe that Andean civilizations first developed on the narrow coastal plain of the Pacific Ocean. The Caral or Norte Chico civilization of coastal Peru is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, dating back to 3500 BCE. Andean civilization is one of the six "pristine" civilizations of the world, created independently and without influence by other civilizations.

The Tawantinsuyu or Inca Empire was a centralized bureaucracy. It drew upon the administrative forms and practices of previous Andean civilizations such as the Wari Empire and Tiwanaku, and had in common certain practices with its contemporary rivals, notably the Chimor. These institutions and practices were understood, articulated, and elaborated through Andean cosmology and thought. Following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, certain aspects of these institutions and practices were continued.

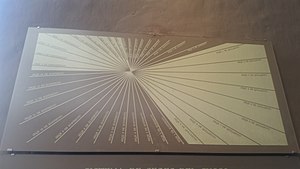

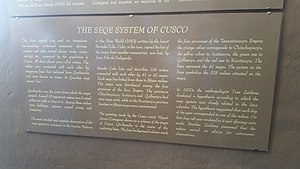

The ceque system was a series of ritual pathways leading outward from Cusco into the rest of the Inca Empire. The empire was divided into four sections called suyus. In fact, the local name for the empire was "Tawantinsuyu," meaning "four parts together." Cusco, the capital, was the center and meeting point of these four sections, which converged at Qurikancha, the temple of the sun. Cusco was split in half, Hanansaya to the north and Hurinsaya to the south, with each half containing two of the four suyus. Hanansaya contained Chinchaysuyu in the northwest and Antisuyu in the northeast while Hurinsaya contained Qullasuyu in the southeast and Kuntisuyu in the southwest. Each region contained 9 lines, except for the Kuntisuyu, which had 14 or 15. Thus a total of 41 or 42 known pathways radiated out from the Qurikancha or sun temple in Cusco, leading to shrines or wak'as of religious and ceremonial significance.

Amaru Marka Wasi, Amarumarcahuasi or Amaromarcaguaci also known as hispanicized and mixed spellings , Amarumarkahuasi, Amaru Markahuasi), Salunniyuq(Salonniyoq, Salonniyuq), Salunpunku(Salonpunku), Laqu, Laq'u(Lacco, Lago), or Templo de la Luna is an archaeological site in Peru. It is situated in the Cusco Region, Cusco Province, Cusco District, north of the city of Cusco. It lies east of the archaeological site of Sacsayhuamán and south of Tambomachay and Puka Pukara, near Qenko.

Cristóbal de Molina, called «el Cusqueño», was a Spanish colonial clergyman and chronicler who was very fluent in Quechua. He spent most of his life in Cusco, Peru and became a reputable reporter of the pre-Colonial Andean culture.

The situa or citua was the health and ritual purification festival in the Inca Empire. It was held in Cusco, the capital of the empire, during the month of September on the day of the first moon after the spring equinox, which in the southern hemisphere takes place normally on September 23. It was a very important festival whose rites are well described by the early Spanish chroniclers, in particular Cristóbal de Molina, Polo de Ondegardo and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. The latter witnessed situas as a child after the Spaniards had reduced them to memorials of the actual Inca festival. The situa is also mentioned by Bernabé Cobo, who copied, most probably, its text from Molina, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa and Juan de Betanzos.