The names of China include the many contemporary and historical designations given in various languages for the East Asian country known as 中国; 中國; Zhōngguó; 'Central state', 'Middle kingdom' in Standard Chinese, a form based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin.

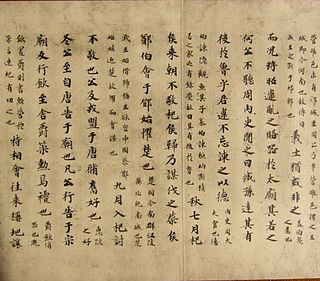

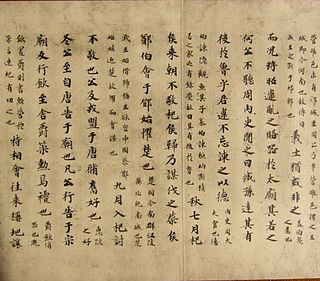

Zhuge Liang, also commonly known by his courtesy name Kongming, was a Chinese statesman, strategist, and inventor who lived through the end of the Eastern Han dynasty and the early Three Kingdoms period (220–280) of China. During the Three Kingdoms period, he served as the Imperial Chancellor of the state of Shu Han (221–263) from its founding in 221 and later as regent from 223 until his death in September or October 234.

Zhou Yu (175–210), courtesy name Gongjin, was a Chinese military general and strategist serving under the warlord Sun Ce in the late Eastern Han dynasty of China. After Sun Ce died in the year 200, he continued serving under Sun Quan, Sun Ce's younger brother and successor. Zhou Yu is primarily known for his leading role in defeating the numerically superior forces of the northern warlord Cao Cao at the Battle of Red Cliffs in late 208, and again at the Battle of Jiangling in 209. Zhou Yu's victories served as the bedrock of Sun Quan's regime, which in 222 became Eastern Wu, one of the Three Kingdoms. Zhou Yu did not live to see Sun Quan's enthronement, however, as he died at the age of 35 in 210 while preparing to invade Yi Province. According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, Zhou Yu was described as tall and handsome. He was also referred to as "Master Zhou". However, his popular moniker "Zhou the Beautiful Youth" does not appear in either the Records or the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Some Japanese writers such as Fumihiko Koide believe that this was a later invention by Japanese storytellers such as Eiji Yoshikawa.

King Jie was the 17th and last ruler of the Xia dynasty of China. He is traditionally regarded as a tyrant and oppressor who brought about the collapse of a dynasty.

Yu the Great or Yu the Engineer was a legendary king in ancient China who was famed for "the first successful state efforts at flood control," his establishment of the Xia dynasty which inaugurated dynastic rule in China, and his upright moral character. He figures prominently in the Chinese legend titled "Great Yu Controls the Waters". Yu and other "sage-kings" of ancient China were lauded for their virtues and morals by Confucius and other Chinese teachers. He is one of the few Chinese monarchs who is posthumously honored with the epithet "the Great".

The Guoyu, usually translated Discourses of the States, is an ancient Chinese text that consists of a collection of speeches attributed to rulers and other men from the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC). It comprises a total of 240 speeches, ranging from the reign of King Mu of Zhou to the execution of the Jin minister Zhibo in 453 BC. The Guoyu was probably compiled beginning in the 5th century BC and continuing to the late 4th century BC. The earliest chapter of the compilation is the Discourses of Zhou.

The Zuo Zhuan, often translated The Zuo Tradition or The Commentary of Zuo, is an ancient Chinese narrative history that is traditionally regarded as a commentary on the ancient Chinese chronicle Spring and Autumn Annals. It comprises 30 chapters covering a period from 722 to 468 BC, and focuses mainly on political, diplomatic, and military affairs from that era.

Zuo Qiuming, Zuoqiu Ming or Qiu Ming was a Chinese historian who was a contemporary of Confucius. He lived in the State of Lu during the Spring and Autumn period. He was a historian, litterateur, thinker and essayist who worked as a Lu official.

The xiezhi is a mythical creature of Chinese origin found throughout Sinospheric legends. It resembles an ox or goat, with thick dark fur covering its body, bright eyes, and a single long horn on its forehead. It has great intellect and understands human speech. The xiezhi possesses the innate ability to distinguish right from wrong, and when it finds corrupt officials, it will ram them with its horn and devour them. It is known as a symbol of justice.

During the late Zhou dynasty, the inhabitants of the Central Plains began to make a distinction between Hua and Yi, referred to by some historians as the Sino–barbarian dichotomy. They defined themselves as part of cultural and political region known as Huaxia, which they contrasted with the surrounding regions home to outsiders, conventionally known as the Four Barbarians. Although Yi is usually translated as "barbarian", other translations of this term in English include "foreigners", "ordinary others", "wild tribes" and "uncivilized tribes". The Hua–Yi distinction asserted Chinese superiority, but implied that outsiders could become Hua by adopting their culture and customs. The Hua–Yi distinction was not unique to China, but was also applied by various Vietnamese, Japanese, and Koreans regimes, all of whom considered themselves at one point in history to be legitimate successors to the Chinese civilization and the "Central State" in imitation of China.

The Nine Tripod Cauldrons were, in Ancient China, a collection of ding that were viewed as symbols of the authority given to the ruler by the mandate of heaven. They had been cast, according to the legend, by Yu the Great of the Xia dynasty.

Xirong or Rong were various people who lived primarily in and around the western extremities of ancient China. They were known as early as the Shang dynasty, as one of the Four Barbarians that frequently interacted with the sinitic Huaxia civilization. They typically resided to the west of Guanzhong Plains from the Zhou Dynasty onwards. They were mentioned in some ancient Chinese texts as perhaps genetically and linguistically related to the people of the Chinese civilization.

Lai, also known as Láiyí (萊夷), was an ancient Dongyi state located in what is now eastern Shandong Province, recorded in the Book of Xia. Tang Shanchun (唐善纯) believes lái means "mountain" in the ancient Yue language (古越语), while the Yue Jue Shu (越絕書) says lai means "wilderness".

The Spring and Autumn Annals is an ancient Chinese chronicle that has been one of the core Chinese classics since ancient times. The Annals is the official chronicle of the State of Lu, and covers a 241-year period from 722 to 481 BC. It is the earliest surviving Chinese historical text to be arranged in annals form. Because it was traditionally regarded as having been compiled by Confucius—after a claim to this effect by Mencius—it was included as one of the Five Classics of Chinese literature.

Little China refers to a politico-cultural ideology and phenomenon in which various Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese regimes identified themselves as the "Central State" and regarded themselves to be legitimate successors to the Chinese civilization. Informed by the traditional Chinese concepts of Sinocentrism and Sino–barbarian dichotomy, this belief became more apparent after the Manchu-led Qing dynasty had superseded the Han-led Ming dynasty in China proper, as Tokugawa Japan, Joseon Korea and Nguyễn Vietnam, among others, perceived that "barbarians" had ruined the center of world civilization.

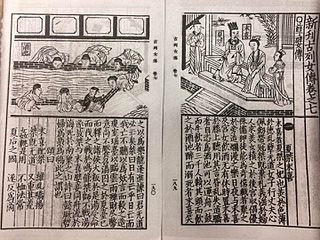

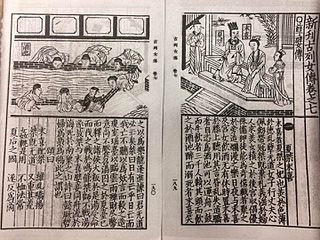

Mo Xi (Chinese: 妺喜; pinyin: Mò Xǐ; Wade–Giles: Mo4Hsi3) was a concubine of Jie, the last ruler of the Chinese Xia dynasty. According to tradition, Mo Xi, Da Ji (concubine of the last ruler of the Shang dynasty) and Bao Si (concubine of the last ruler of the Western Zhou dynasty) are each blamed for the fall of these respective dynasties. According to the Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue, “Xia fell because of Mo Xi; Yin (Shang) fell because of Da Ji; Zhou fell because of Bao Si” (夏亡以妹喜,殷亡以妲己,周亡以褒姒). Neither Mo Xi nor the Lake of Alcohol, with which she is associated, is mentioned in the story of Jie and the fall of Xia dynasty in the Records of the Grand Historian.

The Four Perils are four malevolent beings that existed in Chinese mythology and the antagonistic counterparts of the Four Benevolent Animals.

Genmou was a vassal state during the Zhou Dynasty in Ancient China. Genmou was founded by the Eastern Yi and was conquered by the state of Lu in the 9th year of Lu's Duke Xuan's reign.

Qi Wannian, or Qiwannian, was an ethnic Di chieftain and rebel leader during the Western Jin dynasty of China. In 296, he became the leader of a tribal uprising against Jin in Qin and Yong provinces that lasted until 299. The rebellion raised concerns among some ministers regarding the tension between the Han and tribal people while also triggering a mass migration of refugees into Hanzhong and Sichuan.

The debate on the "Chineseness" of the Yuan and Qing dynasties is concerned with whether the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1912) can be considered "Chinese dynasties", and whether they were representative of "China" during the respective historical periods. The debate, albeit historiographical in nature, has political implications. Mainstream academia and successive governments of China, including the imperial governments of the Yuan and Qing dynasties, have maintained the view that they were "Chinese" and representative of "China". In short, the cause of the controversy stems from the dispute in interpreting the relationship between the two concepts of "Han Chinese" and "China", because although the Chinese government recognizes 56 ethnic groups in China and the Han have a more open view of the Yuan and Qing dynasties since Liang Qichao and other royalist reformers supported the Qing dynasty, the Han are China's main ethnic group. This means that there are many opinions that equate Han Chinese people with China and lead to criticism of the legitimacy of these two dynasties.