Leslie County is located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Its county seat and largest city is Hyden. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,513. It was formed in 1878 from portions of Clay, Harlan, and Perry counties, and named for Preston Leslie, governor of Kentucky from 1871 to 1875.

The Westray Mine was a Canadian coal mine in Plymouth, Nova Scotia. Westray was owned and operated by Curragh Resources Incorporated, which obtained both provincial and federal government money to open the mine, and supply the local electric power utility with coal.

A mining accident is an accident that occurs during the process of mining minerals or metals. Thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially from underground coal mining, although accidents also occur in hard rock mining. Coal mining is considered much more hazardous than hard rock mining due to flat-lying rock strata, generally incompetent rock, the presence of methane gas, and coal dust. Most of the deaths these days occur in developing countries, and rural parts of developed countries where safety measures are not practiced as fully. A mining disaster is an incident where there are five or more fatalities.

The Fraterville Mine disaster was a coal mine explosion that occurred on May 19, 1902 near the community of Fraterville, in the U.S. state of Tennessee. Official records state that 216 miners died as a result of the explosion, from either its initial blast or from the after-effects, making it the worst mining disaster in the United States' history. However, locals claim that the true number of deaths is greater than this because many miners were unregistered and multiple bodies were not identified. The cause of the explosion was likely ignition of methane gas which had built up after leaking from an adjacent unventilated mine.

The Sago Mine disaster was a coal mine explosion on January 2, 2006, at the Sago Mine in Sago, West Virginia, United States, near the Upshur County seat of Buckhannon. The blast and collapse trapped 13 miners for nearly two days; only one survived. It was the worst mining disaster in the United States since the Jim Walter Resources Mine disaster in Alabama on September 23, 2001, and the worst disaster in West Virginia since the 1968 Farmington Mine disaster. It was exceeded four years later by the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster, also a coal mine explosion in West Virginia, which killed 29 miners in April 2010.

The Farmington Mine disaster was an explosion that happened at approximately 5:30 a.m. on November 20, 1968, at the Consol No. 9 coal mine north of Farmington and Mannington, West Virginia, United States.

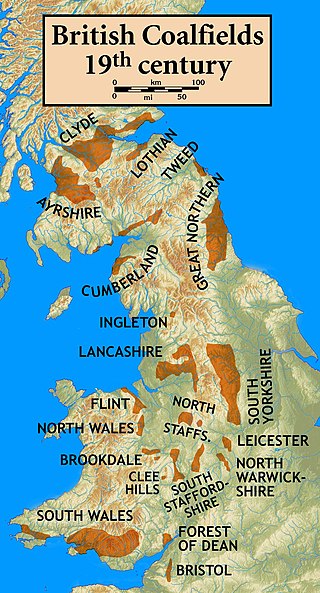

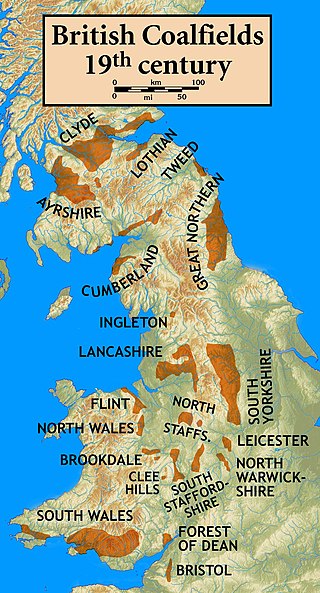

The Oaks explosion, which happened at a coal mine in West Riding of Yorkshire on 12 December 1866, remains the worst mining disaster in England. A series of explosions caused by firedamp ripped through the underground workings at the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill near Stairfoot in Barnsley killing 361 miners and rescuers. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom until the 1913 Senghenydd explosion in Wales.

The Gresford disaster occurred on 22 September 1934 at Gresford Colliery, near Wrexham, Denbighshire, when an explosion and underground fire killed 266 men. Gresford is one of Britain's worst coal mining disasters: a controversial inquiry into the disaster did not conclusively identify a cause, though evidence suggested that failures in safety procedures and poor mine management were contributory factors. Further public controversy was caused by the decision to seal the colliery's damaged sections permanently, meaning that only eleven of those who died were recovered.

The Ulyanovskaya Mine disaster was caused by a methane explosion that occurred on March 19, 2007 in the Ulyanovskaya longwall coal mine in the Kemerovo Oblast. At least 108 people were reported to have been killed by the blast, which occurred at a depth of about 270 meters (885 feet) at 10:19 local time. The mine disaster was Russia's deadliest in more than a decade.

The Darr Mine disaster at Van Meter, Rostraver Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, near Smithton, killed 239 men and boys on December 19, 1907. It ranks as the worst coal mining disaster in Pennsylvanian history. Many victims were of immigrants from central Europe, including Rusyns, Hungarians, Austrians, Germans, Poles and Italians.

The Cross Mountain Mine disaster was a coal mine explosion that occurred on December 9, 1911, near the community of Briceville, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. In spite of a well-organized rescue effort led by the newly created Bureau of Mines, 84 miners died in the disaster. The cause of the explosion was the ignition of dust and methane gas released by a roof fall. Miners would use open oil lamps to provide a light source down in the mines.

The Minnie Pit disaster was a coal mining accident that took place on 12 January 1918 in Halmer End, Staffordshire, in which 155 men and boys died. The disaster, which was caused by an explosion due to firedamp, is the worst ever recorded in the North Staffordshire Coalfield. An official investigation never established what caused the ignition of flammable gases in the pit.

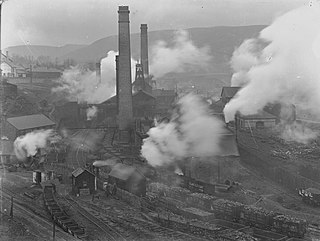

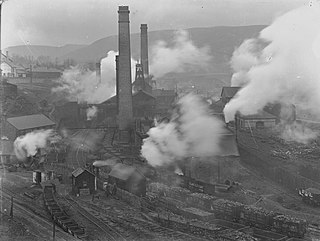

Albion Colliery was a coal mine in South Wales Valleys, located in the village of Cilfynydd, one mile north of Pontypridd.

Two separate explosions in 1903 and 1908 at Hanna Mines, coal mines located in Carbon County, Wyoming, United States, caused a total of over 200 fatalities. The 1903 incident was Wyoming's worst coal mining disaster.

Gresford Colliery was a coal mine located a mile from the North Wales village of Gresford, near Wrexham.

The Upper Big Branch Mine disaster occurred on April 5, 2010 roughly 1,000 feet (300 m) underground in Raleigh County, West Virginia at Massey Energy's Upper Big Branch coal mine located in Montcoal. Twenty-nine out of thirty-one miners at the site were killed. The coal dust explosion occurred at 3:27 pm. The accident was the worst in the United States since 1970, when 38 miners were killed at Finley Coal Company's No. 15 and 16 mines in Hyden, Kentucky. A state funded independent investigation later found Massey Energy directly responsible for the blast.

The Appin coal mine disaster was a coal mine disaster in New South Wales that killed fourteen people: Alexander Lawson, Alwyn Brewin, Francis Garrity, Garry Woods, Geoffrey Johnson, Ian Giffard, James Oldcorn, John Stonham, Jurgen Lauterbach, Karl Staats, Peter Peck, Robert Rawcliffe, Roy Rawlings, and Roy Williams in 1979, where a group of 46 workers were working the 3-11 pm shift and eating in the crib room, approximately 600 metres underground.

The Baltimore Mine Tunnel disaster was an explosion that occurred on June 5, 1919 just inside the mouth of Baltimore Tunnel No. 2. The Delaware and Hudson Coal Company's mine employed 450 workers and was located in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, about a mile from the center of the city near the modern day corner of North Sherman, Spring, and Pine Streets. Ninety-two miners were killed and 44 injured in the explosion, which was caused by the ignition of black blasting powder. Only 7 miners escaped without injury.

The Lundhill Colliery explosion was a coal mining accident which took place on 19 February 1857 in Wombwell, Yorkshire, UK in which 189 men and boys aged between 10 and 59 died. It is one of the biggest industrial disasters in the country's history and it was caused by a firedamp explosion. It was the first disaster to appear on the front page of the Illustrated London News.

The Cymmer Colliery explosion occurred in the early morning of 15 July 1856 at the Old Pit mine of the Cymmer Colliery near Porth, Wales, operated by George Insole & Son. The underground gas explosion resulted in a "sacrifice of human life to an extent unparalleled in the history of coal mining of this country" in which 114 men and boys were killed. Thirty-five widows, ninety-two children, and other dependent relatives were left with no immediate means of support.