Animism is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in some cases words—as being animated, having agency and free will. Animism is used in anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many Indigenous peoples in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Animism is a metaphysical belief which focuses on the supernatural universe : specifically, on the concept of the immaterial soul.

Carl Ransom Rogers was an American psychologist who was one of the founders of humanistic psychology and was known especially for his person-centered psychotherapy. Rogers is widely considered one of the founding fathers of psychotherapy research and was honored for his pioneering research with the Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions by the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1956.

Existentialism is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the issue of human existence. Existentialist philosophers explore questions related to the meaning, purpose, and value of human existence. Common concepts in existentialist thought include existential crisis, dread, and anxiety in the face of an absurd world and free will, as well as authenticity, courage, and virtue.

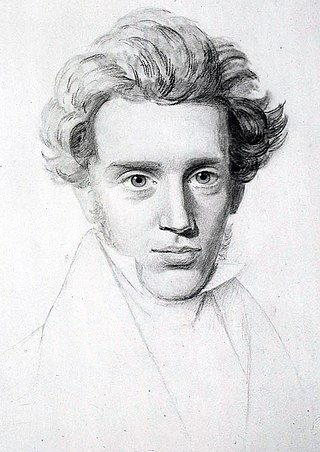

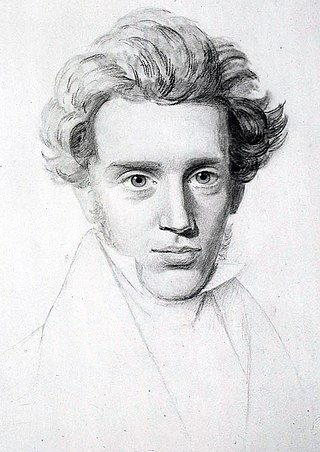

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard was a Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical texts on organized religion, Christianity, morality, ethics, psychology, and the philosophy of religion, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony, and parables. Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a "single individual", giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment. He was against literary critics who defined idealist intellectuals and philosophers of his time, and thought that Swedenborg, Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, Schlegel, and Hans Christian Andersen were all "understood" far too quickly by "scholars."

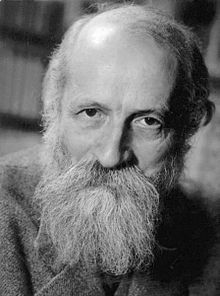

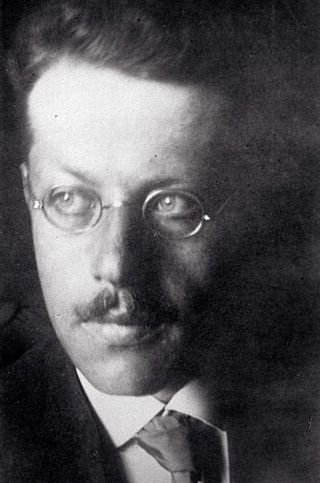

Martin Buber was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship. Born in Vienna, Buber came from a family of observant Jews, but broke with Jewish custom to pursue secular studies in philosophy. He produced writings about Zionism and worked with various bodies within the Zionist movement extensively over a nearly 50-year period spanning his time in Europe and the Near East. In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du, and in 1925, he began translating the Hebrew Bible into the German language reflecting the patterns of the Hebrew language.

Franz Rosenzweig was a German theologian, philosopher, and translator.

Paul Johannes Tillich was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran theologian who was one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century. Tillich taught at German universities before immigrating to the United States in 1933, where he taught at Union Theological Seminary, Harvard University, and the University of Chicago.

Gestalt therapy is a form of psychotherapy that emphasizes personal responsibility and focuses on the individual's experience in the present moment, the therapist–client relationship, the environmental and social contexts of a person's life, and the self-regulating adjustments people make as a result of their overall situation. It was developed by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls and Paul Goodman in the 1940s and 1950s, and was first described in the 1951 book Gestalt Therapy.

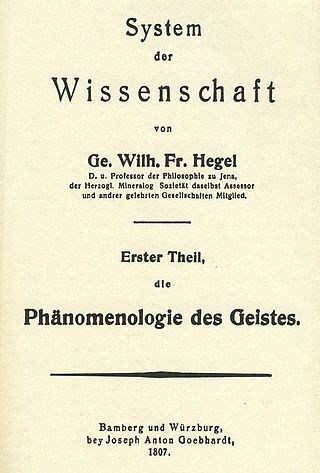

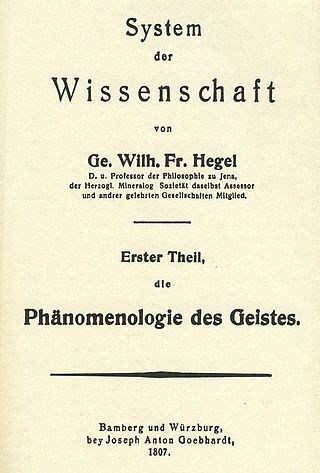

The Phenomenology of Spirit is the most widely-discussed philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel; its German title can be translated as either The Phenomenology of Spirit or The Phenomenology of Mind. Hegel described the work, published in 1807, as an "exposition of the coming to be of knowledge". This is explicated through a necessary self-origination and dissolution of "the various shapes of spirit as stations on the way through which spirit becomes pure knowledge".

In psychology, introjection is the unconscious adoption of the thoughts or personality traits of others. It occurs as a normal part of development, such as a child taking on parental values and attitudes. It can also be a defense mechanism in situations that arouse anxiety. It has been associated with both normal and pathological development.

Person-centered therapy, also known as person-centered psychotherapy, person-centered counseling, client-centered therapy and Rogerian psychotherapy, is a form of psychotherapy developed by psychologist Carl Rogers and colleagues beginning in the 1940s and extending into the 1980s. Person-centered therapy seeks to facilitate a client's actualizing tendency, "an inbuilt proclivity toward growth and fulfillment", via acceptance, therapist congruence (genuineness), and empathic understanding.

Walter Arnold Kaufmann was a German-American philosopher, translator, and poet. A prolific author, he wrote extensively on a broad range of subjects, such as authenticity and death, moral philosophy and existentialism, theism and atheism, Christianity and Judaism, as well as philosophy and literature. He served more than 30 years as a professor at Princeton University.

Existential psychotherapy is a form of psychotherapy based on the model of human nature and experience developed by the existential tradition of European philosophy. It focuses on concepts that are universally applicable to human existence including death, freedom, responsibility, and the meaning of life. Instead of regarding human experiences such as anxiety, alienation and depression as implying the presence of mental illness, existential psychotherapy sees these experiences as natural stages in a normal process of human development and maturation. In facilitating this process of development and maturation existential psychotherapy involves a philosophical exploration of an individual's experiences while stressing the individual's freedom and responsibility to facilitate a higher degree of meaning and well-being in his or her life.

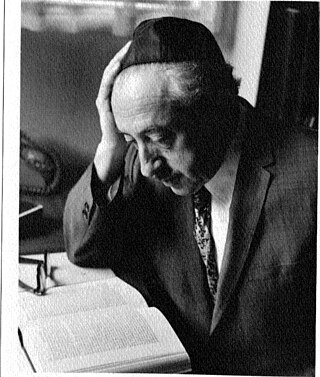

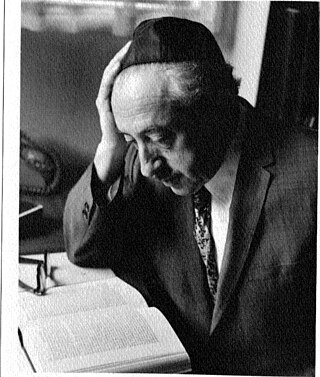

Eliezer Berkovits, was a rabbi, theologian, and educator in the tradition of Orthodox Judaism.

Philosophical anthropology, sometimes called anthropological philosophy, is a discipline dealing with questions of metaphysics and phenomenology of the human person.

The face-to-face relation is a concept in the French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas' thought on human sociality. It means that, ethically, people are responsible to one-another in the face-to-face encounter. Specifically, Lévinas says that the human face "orders and ordains" us. It calls the subject into "giving and serving" the Other.

Phenomenology or phenomenological psychology, a sub-discipline of psychology, is the scientific study of subjective experiences. It is an approach to psychological subject matter that attempts to explain experiences from the point of view of the subject via the analysis of their written or spoken words. The approach has its roots in the phenomenological philosophical work of Edmund Husserl.

Daseinsanalysis is an existentialist approach to psychoanalysis. It was first developed by Ludwig Binswanger in the 1920s under the concept of "phenomenological anthropology". After the publication of "Basic Forms and Perception of Human Dasein", Binswanger would refer to his approach as Daseinsanalysis. Binswanger's approach was heavily influenced by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger and psychoanalysis founder Sigmund Freud. The philosophy of daseinsanalysis is centered on the thought that the human Dasein is open to any and all experience, and that the phenomenological world is experienced freely in an undistorted way. This way initially being absent from meaning, is the basis for analysis. This theory goes opposite to dualism in the way that it proposes no gap between the human mind and measurable matter. Subjects are taught to think in the terms of being alone with oneself and grasping concepts of personhood, mortality and the dilemma or paradox of living in relationship with other humans while being ultimately alone with oneself. Binswanger believed that all mental issues stemmed from the dilemma of living with other humans and being ultimately alone.

Jewish existentialism is a category of work by Jewish authors dealing with existentialist themes and concepts, and intended to answer theological questions that are important in Judaism. The existential angst of Job is an example from the Hebrew Bible of the existentialist theme. Theodicy and post-Holocaust theology make up a large part of 20th century Jewish existentialism.

Philosophy of dialogue is a type of philosophy based on the work of the Austrian-born Jewish philosopher Martin Buber best known through its classic presentation in his 1923 book I and Thou. For Buber, the fundamental fact of human existence, too readily overlooked by scientific rationalism and abstract philosophical thought, is "man with man", a dialogue which takes place in the "sphere of between".