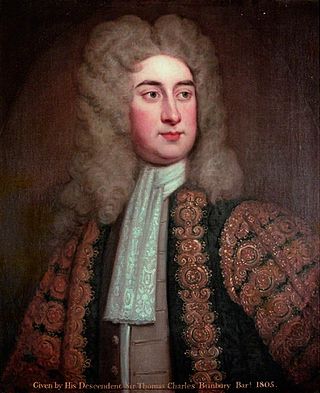

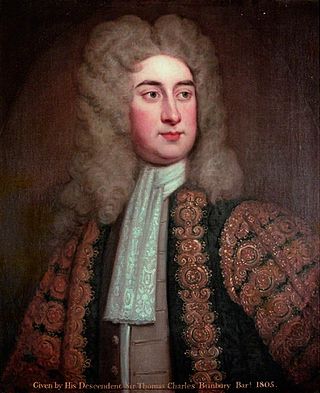

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford,, known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader of the House of Commons, is generally regarded as the de facto first Prime Minister of Great Britain.

James FitzJames Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormonde, (1665–1745) was an Irish statesman and soldier. He was the third of the Kilcash branch of the family to inherit the earldom of Ormond. Like his grandfather, the 1st Duke, he was raised as a Protestant, unlike his extended family who held to Roman Catholicism. He served in the campaign to put down the Monmouth Rebellion, in the Williamite War in Ireland, in the Nine Years' War and in the War of the Spanish Succession but was accused of treason and went into exile after the Jacobite rising of 1715.

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke was an English politician, government official and political philosopher. He was a leader of the Tories, and supported the Church of England politically despite his antireligious views and opposition to theology. He supported the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 which sought to overthrow the new king George I. Escaping to France he became foreign minister for the Pretender. He was attainted for treason, but reversed course and was allowed to return to England in 1723. According to Ruth Mack, "Bolingbroke is best known for his party politics, including the ideological history he disseminated in The Craftsman (1726–1735) by adopting the formerly Whig theory of the Ancient Constitution and giving it new life as an anti-Walpole Tory principle."

James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope was a British soldier, diplomat and statesman who effectively served as Chief Minister between 1717 and 1721. He is also the last Chancellor of the Exchequer to sit in the House of Lords.

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, KG PC FRS was an English statesman and peer of the late Stuart and early Georgian periods. He began his career as a Whig, before defecting to a new Tory ministry. He was raised to the peerage of Great Britain as an earl in 1711. Between 1711 and 1714 he served as Lord High Treasurer, effectively Queen Anne's chief minister. He has been called a prime minister, although it is generally accepted that the de facto first minister to be a prime minister was Robert Walpole in 1721.

The Tories were a loosely organised political faction and later a political party, in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. They first emerged during the 1679 Exclusion Crisis, when they opposed Whig efforts to exclude James, Duke of York from the succession on the grounds of his Catholicism. Despite their fervent opposition to state-sponsored Catholicism, Tories opposed exclusion in the belief inheritance based on birth was the foundation of a stable society.

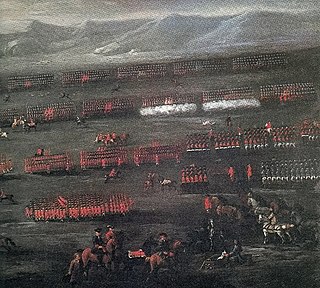

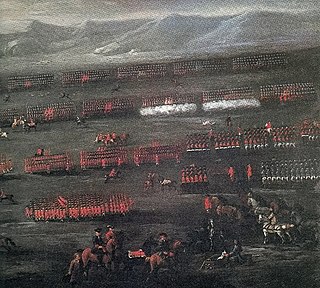

John Erskine, 23rd and 6th Earl of Mar, KT, was a Scottish Jacobite who was the eldest son of Charles, 22nd and 5th Earl of Mar, from whom he inherited estates that were heavily loaded with debt. He was the 23rd Earl of Mar in the first creation of the earldom. He was also the sixth earl in the seventh creation. He was nicknamed Bobbing John, for his tendency to shift back and forth from faction to faction, whether from Tory to Whig or Hanoverian to Jacobite. Deprived of office by the new king in 1714, Mar raised the standard of rebellion against the Hanoverians; at the battle of Sheriffmuir in November 1715, Mar's forces outnumbered those of his opponent, but victory eluded him. At Fetteresso his cause was lost, and Mar fled to France, where he would spend the remainder of his life. The parliament passed a Writ of Attainder against Mar, for treason, in 1716 as punishment for his disloyalty, which was not lifted until 1824. He died in 1732.

The Patriot Whigs, later the Patriot Party, were a group within the Whig Party in Great Britain from 1725 to 1803. The group was formed in opposition to the government of Robert Walpole in the House of Commons in 1725, when William Pulteney and seventeen other Whigs joined with the Tory Party in attacks against the ministry. By the mid-1730s, there were over one hundred opposition Whigs in the Commons, many of whom embraced the Patriot label. For many years, they provided a more effective opposition to the Walpole administration than the Tories were.

Events from the year 1715 in Great Britain.

Thomas Coningsby, 1st Earl Coningsby PC of Hampton Court Castle, Herefordshire, was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times from 1679 until 1716 when he was created a peer and sat in the House of Lords

Edward Harley was a British Tory politician. He sat as Member of Parliament for twenty seven years supporting the group led by his brother, Robert Harley. He was also Auditor of the Imprests. Because of this, and to distinguish him from other family members of the same name, is frequently known as Auditor Harley.

The Harleyministry was the British government that existed between 1710 and 1714 in the reign of Queen Anne. It was headed by Robert Harley and composed largely of Tories. Harley was a former Whig who had changed sides, bringing down the seemingly powerful Whig Junto and their moderate Tory ally Lord Godolphin. It came during the Rage of Party when divisions between the two factions were at their height, and a "paper war" broke out between their supporters. Amongst those writers supportive of Harley's government were Jonathon Swift, Daniel Defoe, Delarivier Manley, John Arbuthnot and Alexander Pope who clashed with members of the rival Kit-Kat Club.

The Jacobite rising of 1715 was the attempt by James Edward Stuart to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland for the exiled Stuarts.

The Atterbury Plot was a conspiracy led by Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester and Dean of Westminster, aimed at the restoration of the House of Stuart to the throne of Great Britain. It came some years after the unsuccessful Jacobite rising of 1715 and Jacobite rising of 1719, at a time when the Whig government of the new Hanoverian king was deeply unpopular.

In the spring and summer of 1715 a series of riots occurred in England in which High Church mobs attacked over forty Dissenting meeting-houses. The rioters also protested against the first Hanoverian king of Britain, George I and his new Whig government. The riots occurred on symbolic days: 28 May was George I's birthday, 29 May was the anniversary of Charles II's Restoration and 10 June was the birthday of the Jacobite Pretender, James Francis Edward Stuart.

The 4th Parliament of Great Britain was summoned by Queen Anne on 18 August 1713 and assembled on the 12 November 1713. It was dissolved on 15 January 1715 and would be Queen Anne's last Parliament.

Hanoverian Tories were Tory supporters of the Hanoverian Succession of 1714. At the time many Tories favoured the exiled Jacobite James Francis Edward Stuart to take the British and Irish thrones, while their arch rivals the Whigs supported the candidacy of George, Elector of Hanover.

The Whig Split occurred between 1717 and 1720, when the British Whig Party divided into two factions: one in government, led by James Stanhope; the other in opposition, dominated by Robert Walpole. It coincided with a dispute between George I and his son George, Prince of Wales, with the latter siding with the opposition Whigs. It is also known as the Whig Schism.

The Peerage Bill was a 1719 measure proposed by the British Whig government led by James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope, and Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland, which would have largely halted the creation of new peerages, limiting membership of the House of Lords.

Harley's Dozen were twelve new peerages created in December 1711 by the British Tory government of Robert Harley which was struggling to gain a majority in the Whig-dominated House of Lords. This came at a time when the government were negotiating peace terms to end the ongoing War of the Spanish Succession, which were unlikely to pass the Lords where opposition Whigs and some Tories had joined together to block them under the slogan "No Peace Without Spain".