Related Research Articles

Motivation is an internal state that propels individuals to engage in goal-directed behavior. It is often understood as a force that explains why people or animals initiate, continue, or terminate a certain behavior at a particular time. It is a complex phenomenon and its precise definition is disputed. It contrasts with amotivation, which is a state of apathy or listlessness. Motivation is studied in fields like psychology, motivation science, and philosophy.

In general, incentives are anything that persuade a person to alter their behavior in the desired manner. It is emphasized that incentives matter by the basic law of economists and the laws of behavior, which state that higher incentives amount to greater levels of effort and therefore higher levels of performance.

Content theory is a subset of motivational theories that try to define what motivates people. Content theories of motivation often describe a system of needs that motivate peoples' actions. While process theories of motivation attempt to explain how and why our motivations affect our behaviors, content theories of motivation attempt to define what those motives or needs are. Content theory includes the work of David McClelland, Abraham Maslow and other psychologists.

Motivational salience is a cognitive process and a form of attention that motivates or propels an individual's behavior towards or away from a particular object, perceived event or outcome. Motivational salience regulates the intensity of behaviors that facilitate the attainment of a particular goal, the amount of time and energy that an individual is willing to expend to attain a particular goal, and the amount of risk that an individual is willing to accept while working to attain a particular goal.

The overjustification effect occurs when an expected external incentive such as money or prizes decreases a person's intrinsic motivation to perform a task. Overjustification is an explanation for the phenomenon known as motivational "crowding out". The overall effect of offering a reward for a previously unrewarded activity is a shift to extrinsic motivation and the undermining of pre-existing intrinsic motivation. Once rewards are no longer offered, interest in the activity is lost; prior intrinsic motivation does not return, and extrinsic rewards must be continuously offered as motivation to sustain the activity.

The somatic marker hypothesis, formulated by Antonio Damasio and associated researchers, proposes that emotional processes guide behavior, particularly decision-making.

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a macro theory of human motivation and personality that concerns people's innate growth tendencies and innate psychological needs. It pertains to the motivation behind people's choices in the absence of external influences and distractions. SDT focuses on the degree to which human behavior is self-motivated and self-determined.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is a prefrontal cortex region in the frontal lobes of the brain which is involved in the cognitive process of decision-making. In non-human primates it consists of the association cortex areas Brodmann area 11, 12 and 13; in humans it consists of Brodmann area 10, 11 and 47.

Motivation crowding theory is the theory from psychology and microeconomics suggesting that providing extrinsic incentives for certain kinds of behavior—such as promising monetary rewards for accomplishing some task—can sometimes undermine intrinsic motivation for performing that behavior. The result of lowered motivation, in contrast with the predictions of neoclassical economics, can be an overall decrease in the total performance.

Frontostriatal circuits are neural pathways that connect frontal lobe regions with the striatum and mediate motor, cognitive, and behavioural functions within the brain. They receive inputs from dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic, and cholinergic cell groups that modulate information processing. Frontostriatal circuits are part of the executive functions. Executive functions include the following: selection and perception of important information, manipulation of information in working memory, planning and organization, behavioral control, adaptation to changes, and decision making. These circuits are involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease as well as neuropsychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and in neurodevelopmental disorder such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The reward system is a group of neural structures responsible for incentive salience, associative learning, and positively-valenced emotions, particularly ones involving pleasure as a core component. Reward is the attractive and motivational property of a stimulus that induces appetitive behavior, also known as approach behavior, and consummatory behavior. A rewarding stimulus has been described as "any stimulus, object, event, activity, or situation that has the potential to make us approach and consume it is by definition a reward". In operant conditioning, rewarding stimuli function as positive reinforcers; however, the converse statement also holds true: positive reinforcers are rewarding.

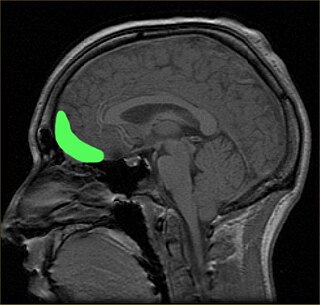

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is a part of the prefrontal cortex in the mammalian brain. The ventral medial prefrontal is located in the frontal lobe at the bottom of the cerebral hemispheres and is implicated in the processing of risk and fear, as it is critical in the regulation of amygdala activity in humans. It also plays a role in the inhibition of emotional responses, and in the process of decision-making and self-control. It is also involved in the cognitive evaluation of morality.

Desires are states of mind that are expressed by terms like "wanting", "wishing", "longing" or "craving". A great variety of features is commonly associated with desires. They are seen as propositional attitudes towards conceivable states of affairs. They aim to change the world by representing how the world should be, unlike beliefs, which aim to represent how the world actually is. Desires are closely related to agency: they motivate the agent to realize them. For this to be possible, a desire has to be combined with a belief about which action would realize it. Desires present their objects in a favorable light, as something that appears to be good. Their fulfillment is normally experienced as pleasurable in contrast to the negative experience of failing to do so. Conscious desires are usually accompanied by some form of emotional response. While many researchers roughly agree on these general features, there is significant disagreement about how to define desires, i.e. which of these features are essential and which ones are merely accidental. Action-based theories define desires as structures that incline us toward actions. Pleasure-based theories focus on the tendency of desires to cause pleasure when fulfilled. Value-based theories identify desires with attitudes toward values, like judging or having an appearance that something is good.

Consumer neuroscience is the combination of consumer research with modern neuroscience. The goal of the field is to find neural explanations for consumer behaviors in individuals both with or without disease.

Cognitive evaluation theory (CET) is a theory in psychology that is designed to explain the effects of external consequences on internal motivation. Specifically, CET is a sub-theory of self-determination theory that focuses on competence and autonomy while examining how intrinsic motivation is affected by external forces in a process known as motivational "crowding out."

Compensation and benefits (C&B) is a sub-discipline of human resources, focused on employee compensation and benefits policy-making. While compensation and benefits are tangible, there are intangible rewards such as recognition, work-life and development. Combined, these are referred to as total rewards. The term "compensation and benefits" refers to the discipline as well as the rewards themselves.

Warm-glow giving is an economic theory describing the emotional reward of giving to others. According to the original warm-glow model developed by James Andreoni, people experience a sense of joy and satisfaction for "doing their part" to help others. This satisfaction - or "warm glow" - represents the selfish pleasure derived from "doing good", regardless of the actual impact of one's generosity. Within the warm-glow framework, people may be "impurely altruistic", meaning they simultaneously maintain both altruistic and egoistic (selfish) motivations for giving. This may be partially due to the fact that "warm glow" sometimes gives people credit for the contributions they make, such as a plaque with their name or a system where they can make donations publicly so other people know the "good" they are doing for the community.

Employee motivation is an intrinsic and internal drive to put forth the necessary effort and action towards work-related activities. It has been broadly defined as the "psychological forces that determine the direction of a person's behavior in an organisation, a person's level of effort and a person's level of persistence". Also, "Motivation can be thought of as the willingness to expend energy to achieve a goal or a reward. Motivation at work has been defined as 'the sum of the processes that influence the arousal, direction, and maintenance of behaviors relevant to work settings'." Motivated employees are essential to the success of an organization as motivated employees are generally more productive at the work place.

Reward management is concerned with the formulation and implementation of strategies and policies that aim to reward people fairly, equitably and consistently in accordance with their value to the organization.

Intrinsic motivation in the study of artificial intelligence and robotics is a mechanism for enabling artificial agents to exhibit inherently rewarding behaviours such as exploration and curiosity, grouped under the same term in the study of psychology. Psychologists consider intrinsic motivation in humans to be the drive to perform an activity for inherent satisfaction – just for the fun or challenge of it.

References

- ↑ Demirkaya, Yüksel (2016). New Public Management in Turkey: Local Government Reform. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-27954-9.

- ↑ Fairholm, Matthew R. (2009). Understanding leadership perspectives : theoretical and practical approaches. Gilbert W. Fairholm. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-84902-7. OCLC 405546136.

- ↑ Miller, Karen A.; Deci, Edward L.; Ryan, Richard M. (March 1988). "Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior". Contemporary Sociology. 17 (2): 253. doi:10.2307/2070638. ISSN 0094-3061. JSTOR 2070638.

- ↑ Ntoumanis, Nikos; Ng, Johan Y.Y.; Prestwich, Andrew; Quested, Eleanor; Hancox, Jennie E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Cecilie; Deci, Edward L.; Ryan, Richard M.; Lonsdale, Chris; Williams, Geoffrey C. (2021-04-03). "A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health". Health Psychology Review. 15 (2): 214–244. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529 . hdl: 11250/2680864 . ISSN 1743-7199. PMID 31983293. S2CID 210922061.

- ↑ Conner, M (2015). Predicting and Changing Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. In Google Books. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- ↑ Kazdin, Alan E. (1973). "The effect of vicarious reinforcement on attentive behavior in the classroom1". Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 6 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1901/jaba.1973.6-71. PMC 1310808 . PMID 16795397.

- ↑ Herrmann-Pillath, Carsten (2014). Hegel, Institutions and Economics : Performing the Social. Ivan Boldyrev. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-90754-1. OCLC 868490938.

- 1 2 Manohar, Sanjay G.; Husain, Masud (2016-03-01). "Human ventromedial prefrontal lesions alter incentivisation by reward". Cortex. 76: 104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.01.005 . ISSN 0010-9452. PMC 4786053 . PMID 26874940.

- ↑ "Hypothalamus: What It Is, Function, Conditions & Disorders". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ↑ Yu, Yen; Chang, Acer Y. C.; Kanai, Ryota (2019-01-22). "Boredom-Driven Curious Learning by Homeo-Heterostatic Value Gradients". Frontiers in Neurorobotics. 12: 88. doi: 10.3389/fnbot.2018.00088 . ISSN 1662-5218. PMC 6349823 . PMID 30723402.

- ↑ Blair, R.J.R (2008-08-12). "The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex: functional contributions and dysfunction in psychopathy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1503): 2557–2565. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0027. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2606709 . PMID 18434283.

- ↑ Schoenbaum, Geoffrey; Roesch, Matthew (September 2005). "Orbitofrontal Cortex, Associative Learning, and Expectancies". Neuron. 47 (5): 633–636. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.018. PMC 2628809 . PMID 16129393.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Institute For Government. (2010). MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy. https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/MINDSPACE.pdf

- ↑ Gustafsson, Bo; Knudsen, Christian; M, Uskali, eds. (1993-06-17). Rationality, Institutions and Economic Methodology. doi:10.4324/9780203392805. ISBN 9781134873296.

- ↑ Hofstede, Geert (February 1993). "Cultural constraints in management theories". Academy of Management Perspectives. 7 (1): 81–94. doi:10.5465/ame.1993.9409142061. ISSN 1558-9080.

- ↑ Gerhart, Barry; Fang, Meiyu (June 2005). "National culture and human resource management: assumptions and evidence". The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 16 (6): 971–986. doi:10.1080/09585190500120772. ISSN 0958-5192. S2CID 155068049.

- ↑ Combs, James; Liu, Yongmei; Hall, Angela; Ketchen, David (September 2006). "How Much Do High-Performance Work Practices Matter: A Meta-Analysis of Their Effects on Organizational Performance". Personnel Psychology. 59 (3): 501–528. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00045.x. ISSN 0031-5826.

- ↑ Chan, Kenneth S.; Lai, Jennifer Te; Li, Tingting (July 2022). "Cultural values, genes and savings behavior in China". International Review of Economics & Finance. 80: 134–146. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2022.02.009. S2CID 246856932.

- ↑ Higgins, E. Tory; Pierro, Antonio; Kruglanski, Arie W. (2008), "Re-thinking Culture and Personality", Handbook of Motivation and Cognition Across Cultures, Elsevier, pp. 161–190, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373694-9.00008-8, ISBN 9780123736949 , retrieved 2023-03-28

- 1 2 Kamenica, Emir (2012-09-01). "Behavioral Economics and Psychology of Incentives". Annual Review of Economics. 4 (1): 427–452. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110909. ISSN 1941-1383.

- 1 2 3 Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team. (2010). Applying behavioural insight to health. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/60524/403936_BehaviouralInsight_acc.pdf

- ↑ Harter, Susan (1978). "Effectance Motivation Reconsidered Toward a Developmental Model". Human Development. 21 (1): 34–64. doi:10.1159/000271574. ISSN 1423-0054.

- ↑ Mills, John A. (July 1978). "A summary and criticism of Skinner's early theory of learning". Canadian Psychological Review. 19 (3): 215–223. doi:10.1037/h0081477. ISSN 0318-2096.