Speciesism is a term used in philosophy regarding the treatment of individuals of different species. The term has several different definitions within the relevant literature. Some sources specifically define speciesism as discrimination or unjustified treatment based on an individual's species membership, while other sources define it as differential treatment without regard to whether the treatment is justified or not. Richard D. Ryder, who coined the term, defined it as "a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species". Speciesism results in the belief that humans have the right to use non-human animals, which scholars say is pervasive in the modern society. Studies from 2015 and 2019 suggest that people who support animal exploitation also tend to endorse racist, sexist, and other prejudicial views, which furthers the beliefs in human supremacy and group dominance to justify systems of inequality and oppression.

In livestock agriculture and the meat industry, a slaughterhouse, also called an abattoir, is a facility where livestock animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a meat-packing facility.

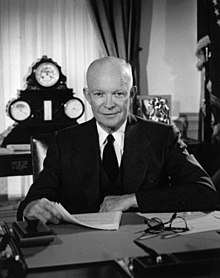

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the relationship between the military and the defense-minded corporations is that both sides benefit—one side from obtaining weapons, and the other from being paid to supply them. The term is most often used in reference to the system behind the armed forces of the United States, where the relationship is most prevalent due to close links among defense contractors, the Pentagon, and politicians. The expression gained popularity after a warning of the relationship's detrimental effects, in the farewell address of U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 17, 1961.

Karen Davis was an American animal rights advocate, and president of United Poultry Concerns, a non-profit organization founded in 1990 to address the treatment of domestic fowl—including chickens, turkeys, and ducks—in factory farming. Davis also maintained a sanctuary.

The prison-industrial complex (PIC) is a term, coined after the "military-industrial complex" of the 1950s, used by scholars and activists to describe the many relationships between institutions of imprisonment and the various businesses that benefit from them.

Commodification is the process of transforming inalienable, free, or gifted things into commodities, or objects for sale. It has a connotation of losing an inherent quality or social relationship when something is integrated by a capitalist marketplace. Concepts that have been argued as being commodified include broad items such as the body, intimacy, public goods, animals and holidays.

Environmental vegetarianism is the practice of vegetarianism that is motivated by the desire to create a sustainable diet, which avoids the negative environmental impact of meat production. Livestock as a whole is estimated to be responsible for around 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, significant reduction in meat consumption has been advocated by, among others, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in their 2019 special report and as part of the 2017 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity.

Steven Best is an American philosopher, writer, speaker and activist. His concerns include animal rights, species extinction, human overpopulation, ecological crisis, biotechnology, liberation politics, terrorism, mass media and culture, globalization, and capitalist domination. He is Associate Professor of Humanities and Philosophy at the University of Texas at El Paso. He has published 13 books and over 200 articles and reviews.

The military–industrial–media complex is an offshoot of the military–industrial complex. Organizations like Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting have accused the military industrial media complex of using their media resources to promote militarism, which, according to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting's hypothesis, benefits the defense resources of the company and allows for a controlled narrative of armed conflicts. In this way, media coverage can be manipulated to show increased effectiveness of weapons systems and to avoid covering civilian casualties, or reducing the emphasis on them. Examples of such coverage include that of the Persian Gulf War, NATO bombing of Yugoslavia and the Iraq War. It is a common practice by defense contractors and weapons systems manufacturers to hire former military personnel as media spokespersons. In 2008, The New York Times found that approximately 75 military analysts – many with military industry ties – were being investigated by the Government Accountability Office and other federal organizations for taking part in a years-long campaign to influence them into becoming "surrogates" for the Bush administration's military policy in the media.

Abolitionism or abolitionist veganism is the animal rights based opposition to all animal use by humans. Abolitionism intends to eliminate all forms of animal use by maintaining that all sentient beings, humans or nonhumans, share a basic right not to be treated as properties or objects. Abolitionists emphasize that the production of animal products requires treating animals as property or resources, and that animal products are not necessary for human health in modern societies. Abolitionists believe that everyone who can live vegan is therefore morally obligated to be vegan.

The Animal Liberation Front (ALF) is an international, leaderless, decentralized political and social resistance movement that advocates and engages in what it calls non-violent direct action in protest against incidents of animal cruelty. It originated in Britain in the 1970s from the Bands of Mercy. Participants state it is a modern-day Underground Railroad, removing animals from laboratories and farms, destroying facilities, arranging safe houses, veterinary care and operating sanctuaries where the animals subsequently live. Critics have labelled them as eco-terrorists.

Toby Miller is a British/Australian-American cultural studies and media studies scholar. He is the author of several books and articles. He was chair of the Department of Media & Cultural Studies at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) and is most recently a professor at Loughborough University. Prior to his academic career, Miller worked in broadcasting, banking, and civil service.

David Alan Nibert is an American sociologist, author, activist and professor of sociology at Wittenberg University. He is the co-organizer of the Section on Animals and Society of the American Sociological Association. In 2005, he received their Award for Distinguished Scholarship.

Attila the Hun has had many depictions in popular culture. Many of these depictions either portray him as a great ruler or a ruthless conqueror. Attila has also appeared in numerous German and Norse epics, under the names Etzel and Atli, both with completely different personas. His sudden death remains a fascinating unsolved mystery.

John Asimakopoulos is an American sociologist and author. He is a professor of sociology at the Bronx Community College of the City University of New York. Asimakopoulos co-founded the Transformative Studies Institute.

Bad-jacketing is a term for planting doubt on the authenticity of an individual's bona fides or identity. An example would be creating suspicion through spreading false rumors, manufacturing evidence, etc., that falsely portray someone in a community organization as an informant, or member of law enforcement, or guilty of malfeasance such as skimming organization funds.

The medical–industrial complex (MIC) refers to a network of interactions between pharmaceutical corporations, health care personnel, and medical conglomerates to supply health care-related products and services for a profit. The term is derived from the idea of the military–industrial complex.

Critical animal studies (CAS) is an interdisciplinary field in the humanities and social sciences and a theory-to-activism global community. It emerged in 2001 with the founding of the Centre for Animal Liberation Affairs by Anthony J. Nocella II and Steven Best, which in 2007 became the Institute for Critical Animal Studies (ICAS). The core interest of CAS is ethical reflection on relations between humans and other animals, firmly grounded in trans-species intersectionality, environmental justice, social justice politics and critical analysis of the underlying role played by the capitalist system. Scholars in the field seek to integrate academic research with political engagement and activism.

Animal–industrial complex (AIC) is a concept used by activists and scholars to describe what they contend is the systematic and institutionalized exploitation of animals. It includes every economic activity involving animals, such as the food industry, animal testing, medicine, clothing, labor and transport, tourism and entertainment, selective breeding, and so forth. Proponents of the term claim that activities described by the term differ from individual acts of animal cruelty in that they constitute institutionalized animal exploitation.