Related Research Articles

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is being presented. Propaganda can be found in a wide variety of different contexts.

The Radio Research Project was a social research project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation to look into the effects of mass media on society.

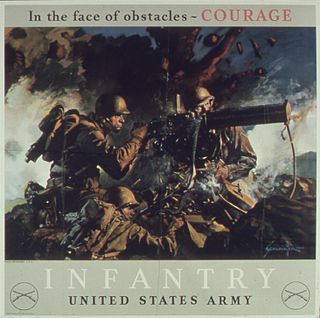

A glittering generality or glowing generality is an emotionally appealing phrase so closely associated with highly valued concepts and beliefs that it carries conviction without supporting information or reason. Such highly valued concepts attract general approval and acclaim. Their appeal is to emotions such as love of country and home, and desire for peace, freedom, glory, and honor. They ask for approval without examination of the reason. They are typically used in propaganda posters/advertisements and used by propagandists and politicians.

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the US in World War I, in particular, the US home front.

Edward Albert Filene was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known for building the Filene's department store chain and for his decisive role in pioneering credit unions across the United States.

Kirtley Fletcher Mather was an American geologist and faculty member at Harvard University. An expert on petroleum geology and mineralogy, Mather was a prominent scholar, advocate for academic freedom, social activist, and critic of McCarthyism. He is known for his efforts to harmonize the dialogue between science and religion, his role in the Scopes "Monkey Trial", his faith-based liberal activism, support for adult education programs and advocacy for civil liberties.

During American involvement in World War II (1941–45), propaganda was used to increase support for the war and commitment to an Allied victory. Using a vast array of media, propagandists instigated hatred for the enemy and support for America's allies, urged greater public effort for war production and victory gardens, persuaded people to save some of their material so that more material could be used for the war effort, and sold war bonds.

Media studies encompasses the academic investigation of the mass media from perspectives such as sociology, psychology, history, semiotics, and critical discourse analysis. The purpose of media studies is to determine how media affects society.

A number of propaganda techniques based on social psychological research are used to generate propaganda. Many of these same techniques can be classified as logical fallacies, since propagandists use arguments that, while sometimes convincing, are not necessarily valid. Propaganda techniques emerge from abusive power and control tactics.

Albert Hadley Cantril, Jr. was an American psychologist from the Princeton University, who expanded the scope of the field.

Leonard William Doob was an American academic who worked as the Sterling Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Yale University and was a pioneering figure in the fields of cognitive and social psychology, propaganda and communication studies, as well as conflict resolution. He served as director of overseas intelligence for the United States Office of War Information in World War II and also wrote several works intersecting cognition, psychology and philosophy.

The Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) is an organization founded in 1951 in counterpoint to the American Sociological Association.

Alfred McClung Lee was an American sociologist whose research included studies of American journalism, propaganda, and race relations.

Counterpropaganda is a form of communication consisting of methods taken and messages relayed to oppose propaganda which seeks to influence action or perspectives among a targeted audience. It is closely connected to propaganda as the two often employ the same methods to broadcast messages to a targeted audience. Counterpropaganda differs from propaganda as it is defensive and responsive to identified propaganda. Additionally, counterpropaganda consists of several elements that further distinguish it from propaganda and ensure its effectiveness in opposing propaganda messages.

The Springfield Plan was a widely publicized intergroup, or intercultural, education policy initiative of the 1940s which was implemented in the public school system of Springfield, Massachusetts. The Plan was the brainchild of Teachers College, Columbia University Associate Professor Clyde R. Miller and the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA). The initiative was the subject of several books, numerous scholarly articles in academic journals, and a Warner Bros. short film starring Andrea King.

Clyde Raymond Miller was an associate professor of education at Teachers College, Columbia University who co-founded the Institute for Propaganda Analysis with Edward A. Filene and Kirtley F. Mather in 1937.

Humanity & Society is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal published by SAGE Publications, and is the official journal of the Association for Humanist Sociology (AHS). Established in 1977, the journal covers all aspects of sociology while focusing on issues of injustice, human suffering and social activism from a humanist point of view. The editor-in-chief is Diana Harvey.

Lloyd A. Free was a pollster who worked with Hadley Cantril and the Institute for International Social Research (IISR).

Percy Shiras Brown was an American chemical, industrial and consulting management engineer, educator, and business executive, who served as president of the Taylor Society in 1924–1925, and as president of the Society for Advancement of Management in 1942–44.

Emma L. Briant is a British scholar and academic researcher on media, contemporary propaganda, surveillance and information warfare who was involved in exposing the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal concerning data misuse and disinformation. She is an associate researcher at Bard College and teaches in the School of Communication at American University. Briant became an honorary associate in Cambridge University Center for Financial Reporting & Accountability, headed by Prof. Alan Jagolinzer, and joined Central European University, as a Fellow in the Center for Media, Data and Society in 2022.

References

- 1 2 Zachary Reich (2014) The Institute for Propaganda Analysis: Protecting Democracy in Pre-World War II America, Institutional Scholarship of Bryn Mawr College

- 1 2 3 4 Sproule, Michael J. (1997) Propaganda and Democracy: The American Experience of Media and Mass Persuasion, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-47022-6

- 1 2 3 Alfred McClung Lee & Elizabeth Briant Lee (1939) The Fine Art of Propaganda: a study of Father Coughlin’s speeches, Harcourt, Brace and Company

- ↑ Arthur B. Moehlman (Nov 1939) "Schools and Propaganda", Michigan Education Journal 17:216–9

- 1 2 Edgar Dale (1940) Propaganda Analysis, an annotated bibliography from HathiTrust

- ↑ Sproule, J. Michael (1997). Propaganda and Democracy: The American Experience of Media and Mass Persuasion. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0521470226.

- ↑ "We Say Au Revoir", Propaganda Analysis 4:1

- 1 2 IPA Propaganda, How To Recognize It and Deal With It, as quoted in S. I. Hayakawa (1939) "General Semantics and Propaganda", Public Opinion Quarterly 3: 197-208.

- Delwiche, Aaron (2005) Propaganda references from Propaganda-critic.

- Garber, William (September 1942) Propaganda Analysis—to what ends? Archived 2007-11-11 at the Wayback Machine , American Journal of Sociology 48(2): 240–245.

- Jowett, Garth S. & O'Donnell, Victoria (1992) Propaganda and Persuasion, SAGE Publications.

- Waples, Douglas (1941) Print, Radio, and Film in a Democracy, University of Chicago Press.