Jürgen Habermas is a German philosopher and social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

In ethics and the social sciences, value theory involves various approaches that examine how, why, and to what degree humans value things and whether the object or subject of valuing is a person, idea, object, or anything else. Within philosophy, it is also known as ethics or axiology.

Action theory is an area in philosophy concerned with theories about the processes causing willful human bodily movements of a more or less complex kind. This area of thought involves epistemology, ethics, metaphysics, jurisprudence, and philosophy of mind, and has attracted the strong interest of philosophers ever since Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. With the advent of psychology and later neuroscience, many theories of action are now subject to empirical testing.

Talcott Parsons was an American sociologist of the classical tradition, best known for his social action theory and structural functionalism. Parsons is considered one of the most influential figures in sociology in the 20th century. After earning a PhD in economics, he served on the faculty at Harvard University from 1927 to 1973. In 1930, he was among the first professors in its new sociology department. Later, he was instrumental in the establishment of the Department of Social Relations at Harvard.

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ability, as in rational animal, to a psychological process, like reasoning, to mental states, such as beliefs and intentions, or to persons who possess these other forms of rationality. A thing that lacks rationality is either arational, if it is outside the domain of rational evaluation, or irrational, if it belongs to this domain but does not fulfill its standards.

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order is contrasted to social chaos or disorder and refers to a stable state of society in which the existing social structure is accepted and maintained by its members. The problem of order or Hobbesian problem, which is central to much of sociology, political science and political philosophy, is the question of how and why it is that social orders exist at all.

Universal pragmatics (UP), more recently placed under the heading of formal pragmatics, is the philosophical study of the necessary conditions for reaching an understanding through communication. The philosopher Jürgen Habermas coined the term in his essay "What is Universal Pragmatics?" where he suggests that human competition, conflict, and strategic action are attempts to achieve understanding that have failed because of modal confusions. The implication is that coming to terms with how people understand or misunderstand one another could lead to a reduction of social conflict.

In moral philosophy, instrumental and intrinsic value are the distinction between what is a means to an end and what is as an end in itself. Things are deemed to have instrumental value if they help one achieve a particular end; intrinsic values, by contrast, are understood to be desirable in and of themselves. A tool or appliance, such as a hammer or washing machine, has instrumental value because it helps you pound in a nail or clean your clothes. Happiness and pleasure are typically considered to have intrinsic value insofar as asking why someone would want them makes little sense: they are desirable for their own sake irrespective of their possible instrumental value. The classic names instrumental and intrinsic were coined by sociologist Max Weber, who spent years studying good meanings people assigned to their actions and beliefs.

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals. According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes account of the behavior of others and is thereby oriented in its course."

In sociology, the term rationalization was coined by Max Weber, a German sociologist, jurist, and economist. Rationalization is the replacement of traditions, values, and emotions as motivators for behaviour in society with concepts based on rationality and reason. The term rational is seen in the context of people, their expressions, and or their actions. This term can be applied to people who can perform speech or in general any action, in addition to the views of rationality within people it can be seen in the perspective of something such as a worldview or perspective (idea). An example of rationalization can be seen in the implementation of bureaucracies in government is a kind of rationalization, as is the construction of high-efficiency living spaces in architecture and urban planning. A potential reason as to why rationalization of a culture may take place in the modern era is the process of globalization. Countries are becoming increasingly interlinked, and with the rise of technology, it is easier for countries to influence each other through social networking, the media and politics. An example of rationalization in place would be the case of witch doctors in certain parts of Africa. Whilst many locals view them as an important part of their culture and traditions, development initiatives and aid workers have tried to rationalize the practice in order to educate the local people in modern medicine and practice.

Discourse ethics refers to a type of argument that attempts to establish normative or ethical truths by examining the presuppositions of discourse. The ethical theory originated with German philosophers Jürgen Habermas and Karl-Otto Apel, and variations have been used by Frank Van Dun and Habermas' student Hans-Hermann Hoppe.

Communicative rationality or communicative reason is a theory or set of theories which describes human rationality as a necessary outcome of successful communication. This theory is in particular tied to the philosophy of German philosophers Karl-Otto Apel and Jürgen Habermas, and their program of universal pragmatics, along with its related theories such as those on discourse ethics and rational reconstruction. This view of reason is concerned with clarifying the norms and procedures by which agreement can be reached, and is therefore a view of reason as a form of public justification.

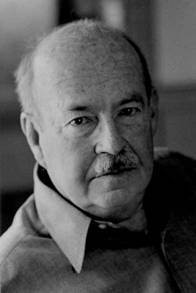

![<i>Between Facts and Norms</i> 1992 book by Jürgen Habermas on [[democracy]] and [[law]]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/46/Between_Facts_and_Norms_%28German_edition%29.jpg)

Between Facts and Norms is a 1992 book on deliberative politics by the German political philosopher Jürgen Habermas. The culmination of the project that Habermas began with The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere in 1962, it represents a lifetime of political thought on the nature of democracy and law.

Lifeworld may be conceived as a universe of what is self-evident or given, a world that subjects may experience together. The concept was popularized by Edmund Husserl, who emphasized its role as the ground of all knowledge in lived experience. It has its origin in biology and cultural Protestantism.

"Instrumental" and "value rationality" are terms scholars use to identify two ways individuals act in order to optimize their behavior. Instrumental rationality recognizes means that "work" efficiently to achieve ends. Value rationality recognizes ends that are "right," legitimate in themselves.

In ethics and social sciences, value denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live, or to describe the significance of different actions. Value systems are prospective and prescriptive beliefs; they affect the ethical behavior of a person or are the basis of their intentional activities. Often primary values are strong and secondary values are suitable for changes. What makes an action valuable may in turn depend on the ethical values of the objects it increases, decreases, or alters. An object with "ethic value" may be termed an "ethic or philosophic good".

In sociology, communicative action is cooperative action undertaken by individuals based upon mutual deliberation and argumentation. The term was developed by German philosopher-sociologist Jürgen Habermas in his work The Theory of Communicative Action.

The Theory of Communicative Action is a two-volume 1981 book by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author continues his project of finding a way to ground "the social sciences in a theory of language", which had been set out in On the Logic of the Social Sciences (1967). The two volumes are Reason and the Rationalization of Society, in which Habermas establishes a concept of communicative rationality, and Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason, in which Habermas creates the two level concept of society and lays out the critical theory for modernity.

Legitimation Crisis is a 1973 book by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas. It was published in English in 1975 by Beacon Press, translated and with an introduction by Thomas McCarthy. It was originally published by Suhrkamp. The title refers to a decline in the confidence of administrative functions, institutions, or leadership: a legitimation crisis. The direct translation of its German title is Legitimation Problems in Late Capitalism. In this book, published five years after Knowledge and Human Interests, Habermas explored the fundamental crisis tendencies in the state-managed capitalism. Before the state-managed capitalism, states are primarily concerned with maintaining the market economy, while in the state-managed capitalism, states have additional roles such as providing a social healthcare, pensions, education, and so on. The expanded scopes of state administrations and influence helped managing crisis tendency of capitalism in economic field, but it created another crisis tendency in political as well as social-cultural field, which is legitimation crisis and motivation crisis, respectively.

The first half of the topic of agency deals with the behavioral sense, or outward expressive evidence thereof. In behavioral psychology, agents are goal-directed entities that are able to monitor their environment to select and perform efficient means-ends actions that are available in a given situation to achieve an intended goal. Behavioral agency, therefore, implies the ability to perceive and to change the environment of the agent. Crucially, it also entails intentionality to represent the goal-state in the future, equifinal variability to be able to achieve the intended goal-state with different actions in different contexts, and rationality of actions in relation to their goal to produce the most efficient action available. Cognitive scientists and Behavioral psychologists have thoroughly investigated agency attribution in humans and non-human animals, since social cognitive mechanisms such as communication, social learning, imitation, or theory of mind presuppose the ability to identify agents and differentiate them from inanimate, non-agentive objects. This ability has also been assumed to have a major effect on inferential and predictive processes of the observers of agents, because agentive entities are expected to perform autonomous behavior based on their current and previous knowledge and intentions. On the other hand, inanimate objects are supposed to react to external physical forces.

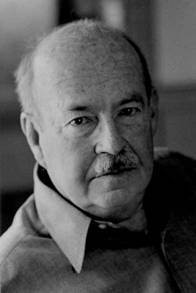

![<i>Between Facts and Norms</i> 1992 book by Jürgen Habermas on [[democracy]] and [[law]]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/46/Between_Facts_and_Norms_%28German_edition%29.jpg)