Related Research Articles

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, or due to the parallels or commonalities in Judaeo-Christian ethics shared by the two religions. The Jewish concept of atonement was appropriated by Christian theologians, and circumcision is a Jewish tradition sometimes still kept by modern evangelical Christians, despite its rejection by Paul in the New Testament.

Polybius was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work The Histories, which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Religion is usually defined as a social-cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, transcendental, and spiritual elements; however, there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion.

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It has had different definitions and interpretations which vary significantly based on historical context and methodological approach.

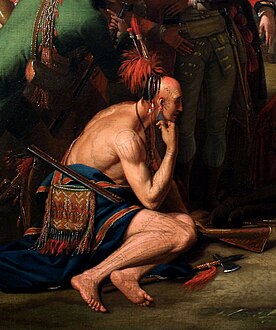

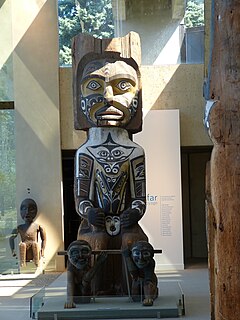

A noble savage is a literary stock character who embodies the concept of the indigene, outsider, wild human, an "other" who has not been "corrupted" by civilization, and therefore symbolizes humanity's innate goodness. Besides appearing in many works of fiction and philosophy, the stereotype was also heavily employed in early anthropological works.

The opium of the people is a dictum used in reference to religion, derived from a frequently paraphrased statement of German sociologist and economic theorist Karl Marx: "Religion is the opium of the people." In context, the statement is part of Marx's structural-functionalist argument that religion was constructed by people to calm uncertainty over their role in the universe and in society.

"There are no atheists in foxholes" is an aphorism used to suggest that times of extreme stress or fear can prompt belief in a higher power. In the context of actual warfare, such a sudden change in belief has been called a foxhole conversion. The logic of the argument is also used to argue for the opposite.

The kyklos is a term used by some classical Greek authors to describe what they considered as the cycle of governments in a society. It was roughly based on the history of Greek city-states in the same period. The concept of the kyklos is first elaborated by Plato, Aristotle, and most extensively Polybius. They all came up with their own interpretation of the cycle, and possible solutions to break the cycle, since they thought the cycle to be harmful. Later writers such as Cicero and Machiavelli commented on the kyklos.

The Harii were, according to 1st century CE Roman historian Tacitus, a Germanic people. In his work Germania, Tacitus describes them as using black shields and painting their bodies, and attacking at night as a shadowy army, much to the terror of their opponents. Theories have been proposed connecting the Harii to the einherjar, ghostly warriors in service to the god Odin, attested much later among the North Germanic peoples by way of Norse mythology, and to the tradition of the Wild Hunt, a procession of the dead through the winter night sky sometimes led by Odin.

Interpretatio graeca or "interpretation by means of Greek [models]" is a discourse used to interpret or attempt to understand the mythology and religion of other cultures; a comparative methodology using ancient Greek religious concepts and practices, deities, and myths, equivalencies, and shared characteristics.

Classical republicanism, also known as civic republicanism or civic humanism, is a form of republicanism developed in the Renaissance inspired by the governmental forms and writings of classical antiquity, especially such classical writers as Aristotle, Polybius, and Cicero. Classical republicanism is built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue and mixed government.

The Discourses on Livy is a work of political history and philosophy written in the early 16th century by the Italian writer and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli, best known as the author of The Prince. The Discourses were published posthumously with papal privilege in 1531.

Tacitean studies, centred on the work of Tacitus the Ancient Roman historian, constitute an area of scholarship extending beyond the field of history. The work has traditionally been read for its moral instruction, its narrative, and its inimitable prose style; Tacitus has been most influential as a political theorist, outside the field of history. The political lessons taken from his work fall roughly into two camps : the "red Tacitists", who used him to support republican ideals, and the "black Tacitists", those who read his accounts as a lesson in Machiavellian realpolitik.

Multitude is a term for a group of people who cannot be classed under any other distinct category, except for their shared fact of existence. Though its use dates back to antiquity, the term first entered into the lexicon of political philosophy when it was used by figures like Machiavelli, Hobbes, and most notably, Spinoza. The multitude is a concept of a population that has not entered into a social contract with a sovereign political body, such that individuals retain the capacity for political self-determination. A multitude typically is classified as a quantity exceeding 100. For Hobbes the multitude was a rabble that needed to enact a social contract with a monarch, thus turning them from a multitude into a people. For Machiavelli and Spinoza both, the role of the multitude vacillates between admiration and contempt. Recently the term has returned to prominence as a new model of resistance against global systems of power as described by political theorists Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in their international best-seller Empire (2000) and expanded upon in their Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (2004). Other theorists recently began to use the term include political thinkers associated with autonomist Marxism and its sequelae, including Sylvère Lotringer, Paolo Virno, and thinkers connected with the eponymous review Multitudes.

The philosophy of war is the area of philosophy devoted to examining issues such as the causes of war, the relationship between war and human nature, and the ethics of war. Certain aspects of the philosophy of war overlap with the philosophy of history, political philosophy, international relations and the philosophy of law.

Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments is a major work by Søren Kierkegaard. The work is an attack against Hegelianism, the philosophy of Hegel, and especially Hegel's Science of Logic. The work is also famous for its dictum, Subjectivity is Truth. It was an attack on what Kierkegaard saw as Hegel's deterministic philosophy. Against Hegel's system, Kierkegaard is often interpreted as taking the side of metaphysical libertarianism or free will, though it has been argued that an incompatibilist conception of free will is not essential to Kierkegaard's formulation of existentialism.

The Machiavellian Moment is a work of intellectual history by J. G. A. Pocock. It posits a connection between republican thought in early 16th century Florence, English-Civil War Britain, and the American Revolution.

The history of political thought encompasses the chronology and the substantive and methodological changes of human political thought. The study of the history of political thought represents an intersection of various academic disciplines, such as philosophy, law, history and political science.

Sociological and anthropological theories about religion generally attempt to explain the origin and function of religion. These theories define what they present as universal characteristics of religious belief and practice.

Marxist–Leninist atheism, also known as Marxist–Leninist scientific atheism, is the irreligious and anti-clerical element of Marxism–Leninism, the official state ideology of the Soviet Union. Based upon a dialectical-materialist understanding of humanity's place in nature, Marxist–Leninist atheism proposes that religion is the opium of the people; thus, Marxism–Leninism advocates atheism, rather than religious belief.

References

- ↑ «Nullum maius boni imperii instrumentum quam bonos amicos esse» Tacitus, Historiae , IV 7. ("No better instrument of good government than being good friends")

- ↑ Polybius, The Histories , VI 56.