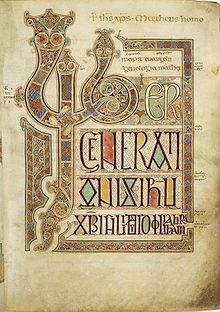

Celtic knots are a variety of knots and stylized graphical representations of knots used for decoration, used extensively in the Celtic style of Insular art. These knots are most known for their adaptation for use in the ornamentation of Christian monuments and manuscripts, such as the 8th-century St. Teilo Gospels, the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. Most are endless knots, and many are varieties of basket weave knots.

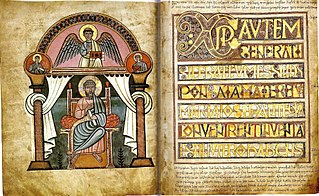

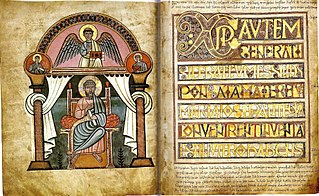

The Lindisfarne Gospels is an illuminated manuscript gospel book probably produced around the years 715–720 in the monastery at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland, which is now in the British Library in London. The manuscript is one of the finest works in the unique style of Hiberno-Saxon or Insular art, combining Mediterranean, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic elements.

The Book of Kells is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables. It was created in a Columban monastery in either Ireland, Scotland or England, and may have had contributions from various Columban institutions from each of these areas. It is believed to have been created c. 800 AD. The text of the Gospels is largely drawn from the Vulgate, although it also includes several passages drawn from the earlier versions of the Bible known as the Vetus Latina. It is regarded as a masterwork of Western calligraphy and the pinnacle of Insular illumination. The manuscript takes its name from the Abbey of Kells, County Meath, which was its home for centuries.

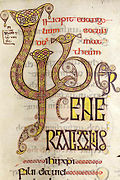

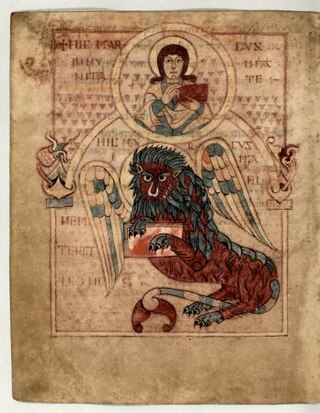

The Book of Durrow is an illuminated manuscript dated to c. 700 that consists of text from the four Gospels gospel books, written in an Irish adaption of Vulgate Latin, and illustrated in the Insular script style.

Codex Usserianus Primus is an early 7th-century Old Latin Gospel Book. It is dated palaeographically to the 6th or 7th century. It is designated by r.

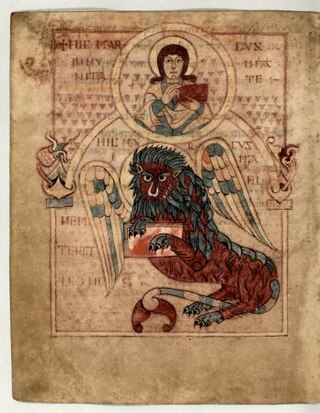

The Book of Cerne is an early ninth-century Insular or Anglo-Saxon Latin personal prayer book with Old English components. It belongs to a group of four such early prayer books, the others being the Royal Prayerbook, the Harleian prayerbook, and the Book of Nunnaminster. It is now commonly believed to have been produced sometime between ca. 820 and 840 AD in the Southumbrian/Mercian region of England. The original book contains a collection of several different texts, including New Testament Gospel excerpts, a selection of prayers and hymns with a version of the Lorica of Laidcenn, an abbreviated or Breviate Psalter, and a text of the Harrowing of Hell liturgical drama, which were combined to provide a source used for private devotion and contemplation. Based on stylistic and palaeographical features, the Book of Cerne has been included within the Canterbury or Tiberius group of manuscripts that were manufactured in southern England in the 8th and 9th centuries AD associated with the Mercian hegemony in Anglo-Saxon England. This Anglo-Saxon manuscript is considered to be the most sophisticated and elaborate of this group. The Book of Cerne exhibits various Irish/Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Continental, and Mediterranean influences in its texts, ornamentation, and embellishment.

The Cathach of St. Columba, known as the Cathach, is a late 6th century Insular psalter. It is the oldest surviving manuscript in Ireland, and the second oldest Latin psalter in the world.

Durham Cathedral Library, Manuscript A.II.10. is a fragmentary seventh-century Insular Gospel Book, produced in Lindisfarne c. 650. Only seven leaves of the book survive, bound in three separate volumes in the Durham Cathedral Dean and Chapter Library. Although this book is fragmentary, it is the earliest surviving example in the series of lavish Insular Gospel Books which includes the Book of Durrow, the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Lichfield Gospels and the Book of Kells.

Insular script was a medieval script system originating from Ireland that spread to Anglo-Saxon England and continental Europe under the influence of Irish Christianity. Irish missionaries took the script to continental Europe, where they founded monasteries such as Bobbio. The scripts were also used in monasteries like Fulda, which were influenced by English missionaries. They are associated with Insular art, of which most surviving examples are illuminated manuscripts. It greatly influenced Irish orthography and modern Gaelic scripts in handwriting and typefaces.

The Stockholm Codex Aureus is a Gospel book written in the mid-eighth century in Southumbria, probably in Canterbury, whose decoration combines Insular and Italian elements. Southumbria produced a number of important illuminated manuscripts during the eighth and early ninth centuries, including the Vespasian Psalter, the Stockholm Codex Aureus, three Mercian prayer books, the Tiberius Bede and the British Library's Royal Bible.

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norman Conquest of England, whose sophisticated art was influential in much of northern Europe. The two periods of outstanding achievement were the 7th and 8th centuries, with the metalwork and jewellery from Sutton Hoo and a series of magnificent illuminated manuscripts, and the final period after about 950, when there was a revival of English culture after the end of the Viking invasions. By the time of the Conquest the move to the Romanesque style is nearly complete. The important artistic centres, in so far as these can be established, were concentrated in the extremities of England, in Northumbria, especially in the early period, and Wessex and Kent near the south coast.

Migration Period art denotes the artwork of the Germanic peoples during the Migration period. It includes the Migration art of the Germanic tribes on the continent, as well the start of the Insular art or Hiberno-Saxon art of the Anglo-Saxon and Celtic fusion in Britain and Ireland. It covers many different styles of art including the polychrome style and the animal style. After Christianization, Migration Period art developed into various schools of Early Medieval art in Western Europe which are normally classified by region, such as Anglo-Saxon art and Carolingian art, before the continent-wide styles of Romanesque art and finally Gothic art developed.

British Library, Egerton MS 609 is a Breton Gospel Book from the late or third quarter of the ninth century. It was created in France, though the exact location is unknown. The large decorative letters which form the beginning of each Gospel are similar to the letters found in Carolingian manuscripts, but the decoration of these letters is closer to that found in insular manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. However, the decoration in the Breton Gospel Book is simpler and more geometric in form than that found in the Insular manuscripts. The manuscript contains the Latin text of St Jerome's letter to Pope Damasus, St. Jerome's commentary on Matthew, and the four Gospels, along with prefatory material and canon tables. This manuscript is part of the Egerton Collection in the British Library.

A carpet page is a full page in an illuminated manuscript containing intricate, non-figurative, patterned designs. They are a characteristic feature of Insular manuscripts, and typically placed at the beginning of a Gospel Book. Carpet pages are characterised by mainly geometrical ornamentation which may include repeated animal forms. They are distinct from pages devoted to highly decorated historiated initials, though the style of decoration may be very similar.

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from insula, the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style different from that of the rest of Europe. Art historians usually group Insular art as part of the Migration Period art movement as well as Early Medieval Western art, and it is the combination of these two traditions that gives the style its special character.

Rath Melsigi was an Anglo-Saxon monastery in Ireland. A number of monks who studied there were active in the Anglo-Saxon mission on the continent. The monastery also developed a style of script that may have influenced the writers of the Book of Durrow.

Lacertines, most commonly found in Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Insular art, are interlaces created by zoomorphic forms. While the term "lacertine" itself means "lizard-like," its use to describe interlace is a 19th-century neologism and not limited to interlace of reptilian forms. In addition to lizards, lacertine decoration often features animals such as birds, lions, and dogs.

In the visual arts, interlace is a decorative element found in medieval art. In interlace, bands or portions of other motifs are looped, braided, and knotted in complex geometric patterns, often to fill a space. Interlacing is common in the Migration period art of Northern Europe, in the early medieval Insular art of Ireland and the British Isles, and Norse art of the Early Middle Ages, and in Islamic art.

Merovingian illumination is the term for the continental Frankish style of illumination in the late seventh and eight centuries, named for the Merovingian dynasty. Ornamental in form, the style consists of initials constructed from lines and circles based on Late Antique illumination, title pages with arcades and crucifixes. Figural images were almost totally absent. From the eight century, zoomorphic decoration began to appear and become so dominant that in some manuscripts from Chelles whole pages are made up of letters formed from animals. Unlike the contemporary Insular illumination with its rampant decoration, the Merovingian style aims for a clean page.