Related Research Articles

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemologists study the nature, origin, and scope of knowledge, epistemic justification, the rationality of belief, and various related issues. Debates in (contemporary) epistemology are generally clustered around four core areas:

- The philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, such as truth and justification

- Potential sources of knowledge and justified belief, such as perception, reason, memory, and testimony

- The structure of a body of knowledge or justified belief, including whether all justified beliefs must be derived from justified foundational beliefs or whether justification requires only a coherent set of beliefs

- Philosophical scepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge, and related problems, such as whether scepticism poses a threat to our ordinary knowledge claims and whether it is possible to refute sceptical arguments

Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to contemplate and act productively using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense, and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowledge, self-transcendence, and non-attachment, and virtues such as ethics and benevolence.

Humility is the quality of being humble. Dictionary definitions accentuate humility as low self-regard and sense of unworthiness. In a religious context, humility can mean a recognition of self in relation to a deity, and subsequent submission to that deity as a member of that religion. Outside of a religious context, humility is defined as being "unselved"—liberated from consciousness of self—a form of temperance that is neither having pride nor indulging in self-deprecation.

Knowledge is an awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often characterized as true belief that is distinct from opinion or guesswork by virtue of justification. While there is wide agreement among philosophers that propositional knowledge is a form of true belief, many controversies focus on justification. This includes questions like how to understand justification, whether it is needed at all, and whether something else besides it is needed. These controversies intensified in the latter half of the 20th century due to a series of thought experiments that provoked alternative definitions.

Critical thinking is the analysis of available facts, evidence, observations, and arguments in order to form a judgement by the application of rational, skeptical, and unbiased analyses and evaluation. The application of critical thinking includes self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective habits of the mind, thus a critical thinker is a person who practices the skills of critical thinking or has been trained and educated in its disciplines. Philosopher Richard W. Paul said that the mind of a critical thinker engages the person's intellectual abilities and personality traits. Critical thinking presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use in effective communication and problem solving, and a commitment to overcome egocentrism and sociocentrism.

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, development, and exercise of the intellect, and is identified with the life of the mind of the intellectual. In the field of philosophy, the term intellectualism indicates one of two ways of critically thinking about the character of the world: (i) rationalism, which is knowledge derived solely from reason; and (ii) empiricism, which is knowledge derived solely from sense experience. Each intellectual approach attempts to eliminate fallacies that ignore, mistake, or distort evidence about "what ought to be" instead of "what is" the character of the world.

Phronesis is a type of wisdom or intelligence relevant to practical action. It implies both good judgment and excellence of character and habits, and was a common topic of discussion in ancient Greek philosophy. Classical works about this topic are still influential today. In Aristotelian ethics, the concept was distinguished from other words for wisdom and intellectual virtues—such as episteme and sophia—because of its practical character. The traditional Latin translation is prudentia, which is the source of the English word "prudence".

Virtue epistemology is a current philosophical approach to epistemology that stresses the importance of intellectual and specifically epistemic virtues. Virtue epistemology evaluates knowledge according to the properties of the persons who hold beliefs in addition to or instead of the properties of the propositions and beliefs. Some advocates of virtue epistemology also adhere to theories of virtue ethics, while others see only loose analogy between virtue in ethics and virtue in epistemology.

Metacognition is an awareness of one's thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The term comes from the root word meta, meaning "beyond", or "on top of". Metacognition can take many forms, such as reflecting on one's ways of thinking and knowing when and how to use particular strategies for problem-solving. There are generally two components of metacognition: (1) knowledge about cognition and (2) regulation of cognition. A metacognitive model differs from other scientific models in that the creator of the model is per definition also enclosed within it. Scientific models are often prone to distancing the observer from the object or field of study whereas a metacognitive model in general tries to include the observer in the model.

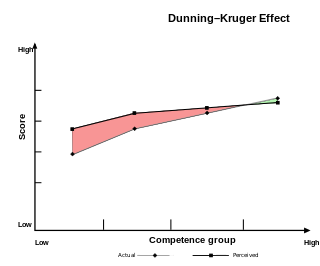

The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people with limited competence in a particular domain overestimate their abilities. Some researchers also include the opposite effect for high performers: their tendency to underestimate their skills. In popular culture, the Dunning–Kruger effect is often misunderstood as a claim about general overconfidence of people with low intelligence instead of specific overconfidence of people unskilled at a particular task.

The overconfidence effect is a well-established bias in which a person's subjective confidence in their judgments is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of those judgments, especially when confidence is relatively high. Overconfidence is one example of a miscalibration of subjective probabilities. Throughout the research literature, overconfidence has been defined in three distinct ways: (1) overestimation of one's actual performance; (2) overplacement of one's performance relative to others; and (3) overprecision in expressing unwarranted certainty in the accuracy of one's beliefs.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the human self:

Quassim Cassam, is professor of philosophy at the University of Warwick. He writes on self-knowledge, perception, epistemic vices and topics in Kantian epistemology. As blurbed for his book, Vices of the Mind (2019), Cassam defines epistemic vice as "character traits, attitudes or thinking styles that prevent us from gaining, keeping or sharing knowledge".

Socratic questioning is an educational method named after Socrates that focuses on discovering answers by asking questions of students. According to Plato, Socrates believed that "the disciplined practice of thoughtful questioning enables the scholar/student to examine ideas and be able to determine the validity of those ideas". Plato explains how, in this method of teaching, the teacher assumes an ignorant mindset in order to compel the student to assume the highest level of knowledge. Thus, a student is expected to develop the ability to acknowledge contradictions, recreate inaccurate or unfinished ideas, and critically determine necessary thought.

The ethics of belief refers to a cluster of related issues that focus on standards of rational belief, intellectual excellence, and conscientious belief-formation. Among the questions addressed in the field are:

Open-mindedness is receptiveness to new ideas. Open-mindedness relates to the way in which people approach the views and knowledge of others. Jason Baehr defines an open-minded person as one who "characteristically moves beyond or temporarily sets aside his own doxastic commitments in order to give a fair and impartial hearing to the intellectual opposition". Jack Kwong's definition sees open-mindedness as the "willingness to take a novel viewpoint seriously".

In the philosophy of science, epistemic humility refers to a posture of scientific observation rooted in the recognition that (a) knowledge of the world is always interpreted, structured, and filtered by the observer, and that, as such, (b) scientific pronouncements must be built on the recognition of observation's inability to grasp the world in itself. The concept is frequently attributed to the traditions of German idealism, particularly the work of Immanuel Kant, and to British empiricism, including the writing of David Hume. Other histories of the concept trace its origin to the humility theory of wisdom attributed to Socrates in Plato's Apology. James Van Cleve describes the Kantian version of epistemic humility–i.e. that we have no knowledge of things in their "nonrelational respects or ‘in themselves'"–as a form of causal structuralism. More recently, the term has appeared in scholarship in postcolonial theory and critical theory to describe a subject-position of openness to other ways of 'knowing' beyond epistemologies that derive from the Western tradition.

Intellectual courage falls under the philosophical family of intellectual virtues, which stem from a person's doxastic logic.

Definitions of knowledge try to determine the essential features of knowledge. Closely related terms are conception of knowledge, theory of knowledge, and analysis of knowledge. Some general features of knowledge are widely accepted among philosophers, for example, that it constitutes a cognitive success or an epistemic contact with reality and that propositional knowledge involves true belief. Most definitions of knowledge in analytic philosophy focus on propositional knowledge or knowledge-that, as in knowing that Dave is at home, in contrast to knowledge-how (know-how) expressing practical competence. However, despite the intense study of knowledge in epistemology, the disagreements about its precise nature are still both numerous and deep. Some of those disagreements arise from the fact that different theorists have different goals in mind: some try to provide a practically useful definition by delineating its most salient feature or features, while others aim at a theoretically precise definition of its necessary and sufficient conditions. Further disputes are caused by methodological differences: some theorists start from abstract and general intuitions or hypotheses, others from concrete and specific cases, and still others from linguistic usage. Additional disagreements arise concerning the standards of knowledge: whether knowledge is something rare that demands very high standards, like infallibility, or whether it is something common that requires only the possession of some evidence.

References

- 1 2 3 Costello, T. H.; Newton, C.; Lin, H.; Pennycook, G. (6 August 2023). "Metacognitive Blindspot in Intellectual Humility Measures". PsyArXiv Preprints. Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science (SIPS) and the Center for Open Science (COS). Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- 1 2 Hannon, Michael (20 July 2020). "Chapter 7: Intellectual humility and the curse of knowledge". In Tanesini, Alessandra; Lynch, Michael (eds.). Polarisation, Arrogance, and Dogmatism: Philosophical Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 104–119. ISBN 0367260859 . Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- 1 2 Welker, Keith M.; Duong, Mylien; Rakhshani, Andrew; Dieffenbach, Macrina; Coleman, Peter; Peter, Jonathan (15 June 2023). "The Online Educational Program 'Perspectives' Improves Affective Polarization, Intellectual Humility, and Conflict Management" (PDF). Journal of Social and Political Psychology. 11 (2): 439. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- 1 2 Leary, M.R. (2022). "Intellectual Humility as a Route to More Accurate Knowledge, Better Decisions, and Less Conflict". . American Journal of Health Promotion. 36 (8): 1401–1404. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ↑ Plous, Scott (1993). The psychology of judgement and decision making (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. p. 217. ISBN 0070504776.

- ↑ Malmendier, Ulrike; Tate, Geoffrey (2008). "Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market's reaction". Journal of Financial Economics . 89 (1): 20–43. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.07.002. S2CID 12354773.

- ↑ Twardawski, Torsten; Kind, Axel (2023). "Board overconfidence in mergers and acquisitions". Journal of Business Research . 165 (1). doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114026.

- ↑ Pärnamets, Philip; Alfano, Mark; Van Bavel, Jay; Ross, Robert (22 July 2022). "Open-mindedness predicts support for public health measures and disbelief in conspiracy theories during the COVID-19 pandemic". PsyArXiv. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ↑ Krumrei-Mancuso, Elizabeth; Rice Begin, Malika (28 October 2022). ""Cultivating Intellectual Humility in Leaders: Potential Benefits, Risks, and Practical Tools"". American Journal of Health Promotion. 36 (8).

- ↑ Bąk, Wacław; Wójtowicz, Bartosz; Kutnik, Jan (2022). "Intellectual humility: an old problem in a new psychological perspective". Current Issues in Personality Psychology. 10 (2): 85–97. doi: 10.5114/cipp.2021.106999 . ISSN 2353-4192. PMC 10535625 . S2CID 237964643.

- ↑ Hoyle, Rick (20 July 2023). "Chapter 6: Forms of Intellectual Humility and Their Associations with Features of KNowledge, Beliefs, and Opinions". In Ottati, Victor; Stern, Chadly (eds.). Open-Mindedness and Dogmatism in a Polarized World. Oxford University Press. pp. 101–119. ISBN 0197655467 . Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ↑ Haggard, Megan C. (December 2016). Humility as Intellectual Virtue: Assessment and Uses of a Limitations-Owning Perspective of Intellectual Humility (PDF). Baylor University (PhD thesis). p. 2.