Aswan is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel, Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is located on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about 230 km (140 mi) southwest of Aswan. The twin temples were originally carved out of the mountainside in the 13th century BC, during the 19th Dynasty reign of the Pharaoh Ramesses II. Their huge external rock relief figures of Ramesses II have become iconic. His wife, Nefertari, and children can be seen in smaller figures by his feet. Sculptures inside the Great Temple commemorate Ramesses II's heroic leadership at the Battle of Kadesh.

Lake Nasser is a vast reservoir in southern Egypt and northern Sudan. It is one of the largest man-made lakes in the world. Before its creation, the project faced opposition from Sudan as it would encroach on land in the northern part of the country, where many Nubian people lived who would have to be resettled. In the end Sudan's land near the area of Lake Nasser was mostly flooded by the lake. The lake has become an important economic resource in Egypt, improving agriculture and touting robust fishing and tourism industries.

Elephantine is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological digs on the island became a World Heritage Site in 1979, along with other examples of Upper Egyptian architecture, as part of the "Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae".

Lower Nubia is the northernmost part of Nubia, roughly contiguous with the modern Lake Nasser, which submerged the historical region in the 1960s with the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Many ancient Lower Nubian monuments, and all its modern population, were relocated as part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia; Qasr Ibrim is the only major archaeological site which was neither relocated nor submerged. The intensive archaeological work conducted prior to the flooding means that the history of the area is much better known than that of Upper Nubia. According to David Wengrow, the A-Group Nubian polity of the late 4th millenninum BCE is poorly understood since most of the archaeological remains are submerged underneath Lake Nasser.

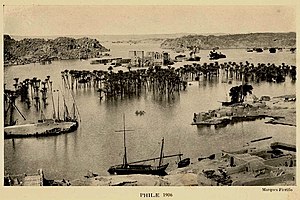

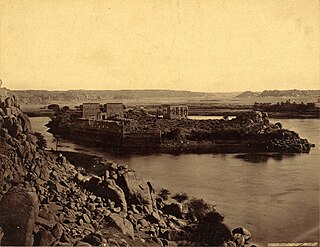

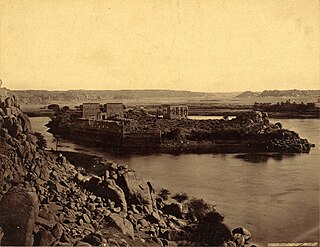

Philae Island was an island near the expansive First Cataract of the Nile in Upper Egypt. Due to the building of the Aswan Dam, the island is today submerged under Lake Nasser. Prior to the submerging, the Philae temple complex which had been built on the island, was moved to Agilkia Island.

Qasr Ibrim is an archaeological site in Lower Nubia, located in the modern country of Egypt. The site has a long history of occupation, ranging from as early as the eighth century BC to AD 1813, and was an economic, political, and religious center. Originally it was a major city perched on a cliff above the Nile, but the flooding of Lake Nasser after the construction of the Aswan High Dam – with the related International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia – transformed it into an island and flooded its outskirts. Qasr Ibrim is the only major archaeological site in Lower Nubia to have survived the Aswan Dam floods. Both prior to and after the floods, it has remained a major site for archaeological investigations.

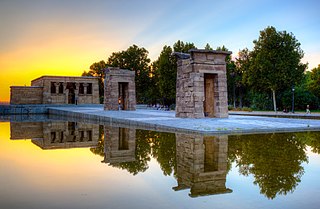

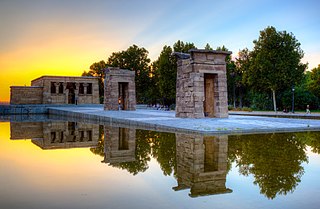

The Temple of Debod is an ancient Nubian temple that was dismantled as part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia and rebuilt in the center of Madrid, Spain, in Parque de la Montaña, Madrid, a square located Calle de Irún, 21–25 Madrid.

Faras was a major city in Lower Nubia. The site of the city, on the border between modern Egypt and Sudan at Wadi Halfa Salient, was flooded by Lake Nasser in the 1960s and is now permanently underwater. Before this flooding, extensive archaeological work was conducted by a Polish archaeological team led by professor Kazimierz Michałowski.

Nobatia or Nobadia was a late antique kingdom in Lower Nubia. Together with the two other Nubian kingdoms, Makuria and Alodia, it succeeded the kingdom of Kush. After its establishment in around 400, Nobadia gradually expanded by defeating the Blemmyes in the north and incorporating the territory between the second and third Nile cataract in the south. In 543, it converted to Coptic Christianity. It would then be annexed by Makuria, under unknown circumstances, during the 7th century.

Christiane Desroches Noblecourt was a French Egyptologist. She was the author of many books on Egyptian art and history and was also known for her role in the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia from flooding caused by the Aswan Dam.

The Temple of Taffeh is an ancient Egyptian temple which was presented to the Netherlands for its help in contributing to the historical preservation of Egyptian antiquities in the 1960s during the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia. The temple was built of sandstone between 25 BCE and 14 CE during the rule of the Roman emperor Augustus. It was part of the Roman fortress known as Taphis and measures 6.5 by 8 metres. The north temple's "two front columns are formed by square pillars with engaged columns" on its four sides. The rear wall of the temple interior features a statue niche.

The Temple of Kalabsha is an ancient Egyptian temple that was originally located at Bab al-Kalabsha, approximately 50 km south of Aswan.

The temples of Wadi es-Sebua, is a pair of New Kingdom Egyptian temples, including one speos temple constructed by the 19th Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II, in Lower Nubia.

The Temple of Amada, the oldest Egyptian temple in Nubia, was first constructed by Pharaoh Thutmose III of the 18th dynasty and dedicated to Amun and Re-Horakhty. His son and successor, Amenhotep II continued the decoration program for this structure. Amenhotep II's successor, Thutmose IV decided to place a roof over its forecourt and transform it into a pillared or hypostyle hall. During the Amarna period, Akhenaten had the name Amun destroyed throughout the temple but this was later restored by Seti I of Egypt's 19th Dynasty. Various 19th Dynasty kings especially Seti I and Ramesses II also "carried out minor restorations and added to the temple's decoration." The stelas of the Viceroys of Kush Setau, Heqanakht and Messuy and that of Chancellor Bay describe their building activities under Ramesses II, Merneptah and Siptah respectively. In the medieval period the temple was converted into a church.

Nubia is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, or more strictly, Al Dabbah. It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, the Kerma culture, which lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under Pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC, whose heirs ruled most of Nubia for the next 400 years. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its 25th Dynasty.

Agilkia Island is an island in the reservoir of the Old Aswan Dam along the Nile River in southern Egypt; it is the present site of the relocated ancient Egyptian temple complex of Philae. Partially to completely flooded by the old dam's construction in 1902, the Philae complex was dismantled and relocated to Agilkia island, as part of a wider UNESCO project related to the 1960s construction of the Aswan High Dam and the eventual flooding of many sites posed by its large reservoir upstream.

The Temple of Ellesyia is an ancient Egyptian rock-cut temple originally located near the site of Qasr Ibrim. It was built during the 18th Dynasty by the Pharaoh Thutmosis III. The temple was dedicated to the deities Amun, Horus and Satis. Tuthmosis III had a small temple carved into the rock at Ellesiya, not far from Abu Simbel, dedicated to Horus of Miam and Satet. The temple is only accessible from the river. The interior features an inverted T-shaped structure, consisting of a corridor and two side chambers. On the walls, scenes depict offerings made by the king to the Egyptian and Nubian gods. The figures face the back wall, where statues of Horus, Satet, and Tuthmosis III on a throne are carved in half-relief.

New Amada is a promontory located near Aswan in Egypt.

Gebel Adda was a mountain and archaeological site on the right bank of the Nubian Nile in what is now southern Egypt. The settlement on its crest was continuously inhabited from the late Meroitic period to the Ottoman period, when it was abandoned by the late 18th century. It reached its greatest prominence in the 14th and 15th centuries, when it seemed to have been the capital of late kingdom of Makuria. The site was superficially excavated by the American Research Center in Egypt just before being flooded by Lake Nasser in the 1960s, with much of the remaining excavated material, now stored in the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, remaining unpublished. Unearthed were Meroitic inscriptions, Old Nubian documents, a large amount of leatherwork, two palatial structures and several churches, some of them with their paintings still intact. The nearby ancient Egyptian rock temple of Horemheb, also known as temple of Abu Oda, was rescued and relocated.