Eugenics is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. In recent years, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR and genetic screening, with a heated debate on whether these technologies should be called eugenics or not.

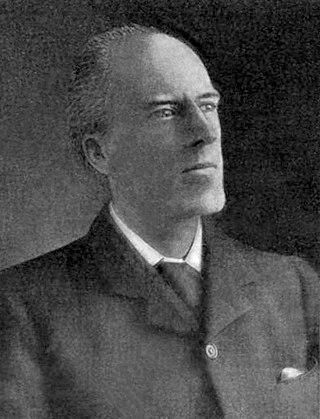

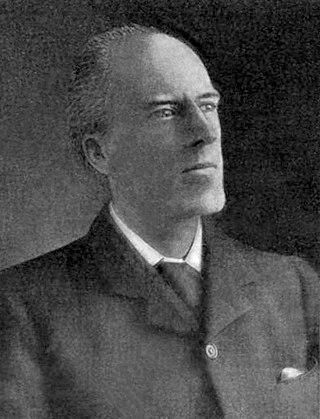

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI, was an English polymath in the Victorian era. He was a proponent of social Darwinism, eugenics, and scientific racism; Galton was knighted in 1909.

Karl Pearson was an English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university statistics department at University College, London in 1911, and contributed significantly to the field of biometrics and meteorology. Pearson was also a proponent of social Darwinism and eugenics, and his thought is an example of what is today described as scientific racism. Pearson was a protégé and biographer of Sir Francis Galton. He edited and completed both William Kingdon Clifford's Common Sense of the Exact Sciences (1885) and Isaac Todhunter's History of the Theory of Elasticity, Vol. 1 (1886–1893) and Vol. 2 (1893), following their deaths.

Madison Grant was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservationist, eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted for his far-reaching achievements in conservation than for his advocacy of Nordicism, a form of racism which views the "Nordic race" as superior.

Paul Bowman Popenoe was an American marriage counselor, eugenicist and agricultural explorer. He was an influential advocate of the compulsory sterilization of mentally ill people and people with mental disabilities, and the father of marriage counseling in the United States.

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity research from 1910 to 1939. It was established by the Carnegie Institution of Washington's Station for Experimental Evolution, and subsequently administered by its Department of Genetics.

Harry Hamilton Laughlin was an American educator and eugenicist. He served as the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from its inception in 1910 to its closure in 1939, and was among the most active individuals influencing American eugenics policy, especially compulsory sterilization legislation.

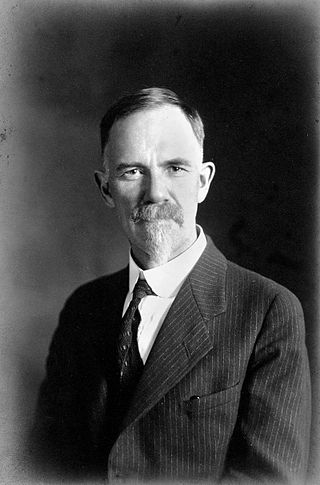

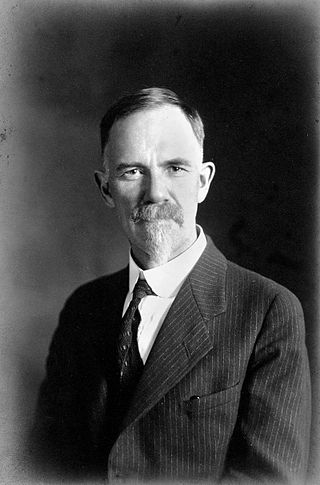

Charles Benedict Davenport was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement.

The Society for Biodemography and Social Biology, formerly known as the Society for the Study of Social Biology and before then as the American Eugenics Society, is dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations."

The Adelphi Genetics Forum is a non-profit learned society based in the United Kingdom. Its aims are "to promote the public understanding of human heredity and to facilitate informed debate about the ethical issues raised by advances in reproductive technology."

Major General Frederick Henry Osborn CBE was an American philanthropist, military leader, and eugenicist. He was a founder of several organizations and played a central part in reorienting eugenics in the years following World War II away from the race- and class-consciousness of earlier periods. The American Philosophical Society considers him to have been "the respectable face of eugenic research in the post-war period."

Heredity in Relation to Eugenics is a book by American eugenicist Charles Benedict Davenport, published in 1911. It argued that many human traits were genetically inherited, and that it would therefore be possible to selectively breed people for desirable traits to improve the human race. It was printed and published with money and support of the Carnegie Institution. The book was widely used as a text for medical schools in the United States and abroad.

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. The cause became increasingly promoted by intellectuals of the Progressive Era.

The International Federation of Eugenic Organizations (IFEO) was an international organization of groups and individuals focused on eugenics. Founded in London in 1912, where it was originally titled the Permanent International Eugenics Committee, it was an outgrowth of the first International Eugenics Congress. In 1925, it was retitled. Factionalism within the organization led to its division in 1933, as splinter group the Latin International Federation of Eugenics Organizations was created to give a home to eugenicists who disliked the concepts of negative eugenics, in which unfit groups and individuals are discouraged or prevented from reproducing. As the views of the Nazi party in Germany caused increasing tension within the group and leadership activity declined, it dissolved in the latter half of the 1930s.

Geza von Hoffmann (1885–1921) was a prominent Austrian-Hungarian eugenicist and writer. He lived for a time in California as the Austrian Vice-Consulate where he observed and wrote on eugenics practices in the United States.

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to eugenics around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Institutions for Defective Delinquents (IDDs) were created in the United States as a result of the eugenic criminology movement. The practices in these IDDs contain many traces of the eugenics that were first proposed by Sir Francis Galton in the late 1800s. Galton believed that "our understanding of the laws of heredity [could be used] to improve the stock of humankind." Galton eventually expanded on these ideas to suggest that individuals deemed inferior, those in prisons or asylums and those with hereditary diseases, would be discouraged from having children.

Gertrude Anna Davenport, was an American zoologist who worked as both a researcher and an instructor at established research centers such as the University of Kansas and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory where she studied embryology, development, and heredity. The wife of Charles Benedict Davenport, a prominent eugenicist, she co-authored several works with her husband. Together, they were highly influential in the United States eugenics movement during the progressive era.

Eugenic feminism was a component of the women's suffrage movement which overlapped with eugenics. Originally coined by the eugenicist Caleb Saleeby, the term has since been applied to summarize views held by some prominent feminists of the United States. Some early suffragettes in Canada, particularly a group known as The Famous Five, also pushed for eugenic policies, chiefly in Alberta and British Columbia.

The Average Young American Male, also known as the Average American Man and the American Adonis, was a 22-inch plaster statue sculpted in 1921 by Jane Davenport Harris as a composite model for the eugenics movement in the United States. The statue was exhibited at the Second and Third International Congresses of Eugenics in 1921 and 1932, respectively, as a visual representation of that which eugenicists considered to be the degeneration of the white race. While the statue received mixed responses from contemporary critics, it inspired the creation of additional composite statues as propaganda for the eugenics movement throughout the mid-twentieth century.