Interactive art is a form of art that involves the spectator in a way that allows the art to achieve its purpose. Some interactive art installations achieve this by letting the observer walk through, over or around them; others ask the artist or the spectators to become part of the artwork in some way.

Postdigital, in artistic practice, is an attitude that is more concerned with being human, than with being digital, similar to the concept of "undigital" introduced in 1995, where technology and society advances beyond digital limitations to achieve a totally fluid multimediated reality that is free from artefacts of digital computation.

The Pleasure of the Text is a 1973 book by the literary theorist Roland Barthes.

Information art, which is also known as informatism or data art, is an emerging art form that is inspired by and principally incorporates data, computer science, information technology, artificial intelligence, and related data-driven fields. The information revolution has resulted in over-abundant data that are critical in a wide range of areas, from the Internet to healthcare systems. Related to conceptual art, electronic art and new media art, informatism considers this new technological, economical, and cultural paradigm shift, such that artworks may provide social commentaries, synthesize multiple disciplines, and develop new aesthetics. Realization of information art often take, although not necessarily, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches incorporating visual, audio, data analysis, performance, and others. Furthermore, physical and virtual installations involving informatism often provide human-computer interaction that generate artistic contents based on the processing of large amounts of data.

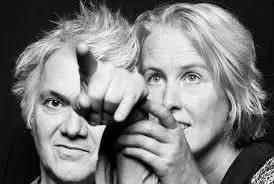

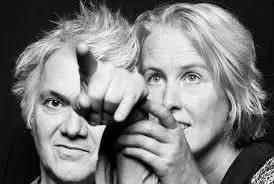

Jodi, is a collective of two internet artists, Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans, created in 1994. They were some of the first artists to create Web art and later started to create software art and artistic computer game modification. Their most well-known art piece is their website wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, which is a landscape of intricate designs made in basic HTML. JODI is represented by Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

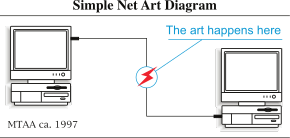

net.art refers to a group of artists who have worked in the medium of Internet art since 1994. Some of the early adopters and main members of this movement include Vuk Ćosić, Jodi.org, Alexei Shulgin, Olia Lialina, Heath Bunting, Daniel García Andújar, and Rachel Baker. Although this group was formed as a parody of avant garde movements by writers such as Tilman Baumgärtel, Josephine Bosma, Hans Dieter Huber and Pit Schultz, their individual works have little in common.

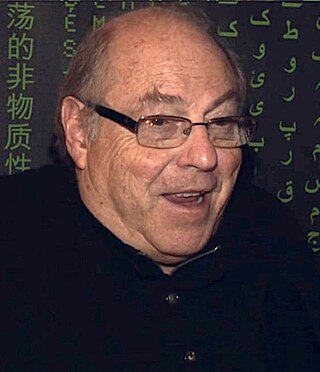

Roy Ascott FRSA is a British artist, who works with cybernetics and telematics on an art he calls technoetics by focusing on the impact of digital and telecommunications networks on consciousness. Since the 1960s, Ascott has been a practitioner of interactive computer art, electronic art, cybernetic art and telematic art.

Yael Kanarek is an Israeli American artist based in New York City that is known for pioneering use of the Internet and of multilingualism in work of art.

Telematic art is a descriptive of art projects using computer-mediated telecommunications networks as their medium. Telematic art challenges the traditional relationship between active viewing subjects and passive art objects by creating interactive, behavioural contexts for remote aesthetic encounters. Telematics was first coined by Simon Nora and Alain Minc in The Computerization of Society. Roy Ascott sees the telematic art form as the transformation of the viewer into an active participator of creating the artwork which remains in process throughout its duration. Ascott has been at the forefront of the theory and practice of telematic art since 1978 when he went online for the first time, organizing different collaborative online projects.

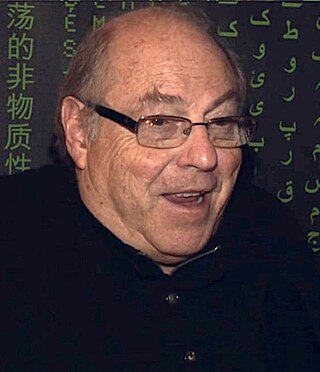

Fred Forest is a French new media artist making use of video, photography, the printed press, mail, radio, television, telephone, telematics, and the internet in a wide range of installations, performances, and public interventions that explore both the ramifications and potential of media space. He was a cofounder of both the Sociological Art Collective (1974) and the Aesthetics of Communication movement (1983).

Rhizome is an American not-for-profit arts organization that supports and provides a platform for new media art.

Cyberformance refers to live theatrical performances in which remote participants are enabled to work together in real time through the medium of the internet, employing technologies such as chat applications or purpose-built, multiuser, real-time collaborative software. Cyberformance is also known as online performance, networked performance, telematic performance, and digital theatre; there is as yet no consensus on which term should be preferred, but cyberformance has the advantage of compactness. For example, it is commonly employed by users of the UpStage platform to designate a special type of Performance art activity taking place in a cyber-artistic environment.

Heath Bunting is a British contemporary artist. Based in Bristol, he is a co-founder of the website irational.org, and was one of the early practitioners in the 1990s of Net.art. Bunting's work is based on creating open and democratic systems by modifying communications technologies and social systems. His work often explores the porosity of borders, both in physical space and online. In 1997, his online work Visitors Guide to London was included in the 10th documenta curated by Swiss curator Simon Lamunière. An activist, he created a dummy site for the European Lab for Network Collision (CERN).

Robert Adrian (1935–2015), also known as Robert Adrian X, was a Canadian artist who made radio and telecommunications art. Adrian moved from Canada to Vienna, Austria in 1972 where he became known for creating experimental artworks using radio and communications technologies. His work The World in 24 Hours, which connected artists in different cities and continents through telephone lines and radio, is considered to be one of the first experiments in online culture. Adrian is considered to be a pioneer in the field of telecommunications art and media art.

New media art includes artworks designed and produced by means of electronic media technologies, comprising virtual art, computer graphics, computer animation, digital art, interactive art, sound art, Internet art, video games, robotics, 3D printing, and cyborg art. The term defines itself by the thereby created artwork, which differentiates itself from that deriving from conventional visual arts. New Media art has origins in the worlds of science, art, and performance. Some common themes found in new media art include databases, political and social activism, Afrofuturism, feminism, and identity, a ubiquitous theme found throughout is the incorporation of new technology into the work. The emphasis on medium is a defining feature of much contemporary art and many art schools and major universities now offer majors in "New Genres" or "New Media" and a growing number of graduate programs have emerged internationally. New media art may involve degrees of interaction between artwork and observer or between the artist and the public, as is the case in performance art. Yet, as several theorists and curators have noted, such forms of interaction, social exchange, participation, and transformation do not distinguish new media art but rather serve as a common ground that has parallels in other strands of contemporary art practice. Such insights emphasize the forms of cultural practice that arise concurrently with emerging technological platforms, and question the focus on technological media per se. New Media art involves complex curation and preservation practices that make collecting, installing, and exhibiting the works harder than most other mediums. Many cultural centers and museums have been established to cater to the advanced needs of new media art.

Ursula Endlicher is a New York City based Austrian multi-media artist who creates works in the fields of internet art, performance art and installation art.

The Poietic Generator is a social-network game designed by Olivier Auber in 1986, and developed from 1987 under the label free art thanks to many contributors. The game takes place within a two-dimensional matrix in the tradition of board games and its principle is similar to both Conway's Game of Life and the surrealists' exquisite corpse.

Annie Abrahams is a Dutch performance artist specialising in video installations and internet based performances, often deriving from collective writings and collective interaction. Born and raised in Hilvarenbeek in the Netherlands, she migrated to and settled in France in 1987. Her performance work challenges and questions the limitations and possibilities of online communication and collaboration. Abrahams describes her body of work as "an aesthetics of trust and attention." Studying biology became an inspiration for her future line of work. "When studying biology I had to observe a colony of monkeys in a zoo. I found this very interesting because I learned something about human communities by watching the apes. In a certain way I watch the internet with the same appetite and interest. I consider it to be a universe where I can observe some aspects of human attitudes and behaviour without interfering."

Cybernetic art is contemporary art that builds upon the legacy of cybernetics, where feedback involved in the work takes precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns. The relationship between cybernetics and art can be summarised in three ways: cybernetics can be used to study art, to create works of art or may itself be regarded as an art form in its own right.

Media art history is an interdisciplinary field of research that explores the current developments as well as the history and genealogy of new media art, digital art, and electronic art. On the one hand, media art histories addresses the contemporary interplay of art, technology, and science. On the other, it aims to reveal the historical relationships and aspects of the ‘afterlife’ in new media art by means of a historical comparative approach. This strand of research encompasses questions of the history of media and perception, of so-called archetypes, as well as those of iconography and the history of ideas. Moreover, one of the main agendas of media art histories is to point out the role of digital technologies for contemporary, post-industrial societies and to counteract the marginalization of according art practices and art objects: ″Digital technology has fundamentally changed the way art is made. Over the last forty years, media art has become a significant part of our networked information society. Although there are well-attended international festivals, collaborative research projects, exhibitions and database documentation resources, media art research is still marginal in universities, museums and archives. It remains largely under-resourced in our core cultural institutions.″