Intersubjective verifiability is the capacity of a concept to be readily and accurately communicated between different individuals ("intersubjectively"), and to be reproduced under varying circumstances for the purposes of verification. It is a core principle of empirical, scientific investigation. [1] [2] [3]

Although there are areas of belief that do not consistently employ intersubjective verifiability (e.g., many religious claims), intersubjective verifiability is a near-universal way of arbitrating truth claims used by people everywhere. In its basic form, it can be found in colloquial expressions, e.g., "I'm from Missouri. Show me!" or "Seeing is believing". The scientific principle of replication of findings by investigators other than those that first reported the phenomenon is simply a more highly structured form of the universal principle of intersubjective verifiability.

Each individual is a subject, and must subjectively experience the physical world. Each subject has a different perspective and point of view on various aspects of the world. However, by sharing their comparable experiences intersubjectively, individuals may gain an increasingly similar understanding of the world. In this way, many different subjective experiences can come together to form intersubjective ones that are less likely to be prone to individual bias or gaps in knowledge.

While specific internal experiences are not intersubjectively verifiable, the existence of thematic patterns of internal experience can be intersubjectively verified. For example, whether or not people are telling what they believe to be the truth when they make claims can only be known by the claimants. However, we can intersubjectively verify that people almost universally experience discomfort (hunger) when they haven't had enough to eat. We generally have only a crude ability to compare (measure) internal experiences.

When an external, public phenomenon is experienced and carefully described (in words or measurements) by one individual, other individuals can see if their experiences of the phenomenon "fit" the description. If they do, a sense of congruence between one subject and another occurs. This is the basis for a definition of what is true that is agreed upon by the involved parties. If the description does not fit the experience of one or more of the parties involved, incongruence occurs instead.

Incongruent contradictions between the experience and descriptions of different individuals can be caused by a number of factors. One common source of incongruence is the inconsistent use of language in the descriptions people use, such as the same words being used differently. Such semantic problems require more careful development and use of language.

Incongruence also arises from a failure to describe the phenomena well. In these cases, further development of the description, model, or theory used to refer to the phenomena is required.

A third form of incongruence arises when the descriptions do not conform to consensual (i.e., intersubjectively verifiable) experience, such as when the descriptions are faulty, incorrect, wrong, or inaccurate, and need to be replaced by more accurate descriptions, models, or theories.

The contradiction between the truths derived from intersubjective verification and beliefs based on faith or on appeal to authority (e.g., many religious beliefs) forms the basis for the conflict between religion and science. [4] There have been attempts to bring the two into congruence, and the modern, cutting edge of science, especially in physics, seems to many observers to lend itself to a melding of religious experience and intersubjective verification of beliefs. Some scientists have described religious worldviews—generally of a mystical nature—consistent with their understanding of science:

There are two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle ...

Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind ...

The religion of the future will be a cosmic religion. The religion which is based on experience, which refuses dogmatism ...

There remains something subtle, intangible and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion. (Albert Einstein)

Other scientists, who are committed to basing belief on intersubjective verification, have called for or predicted the development of a religion consistent with science.

A religion old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the universe as revealed by modern science, might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe hardly tapped by the conventional faiths. Sooner or later, such a religion will emerge. (Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot)

The evolutionary epic is probably the best myth we will ever have ... The true evolutionary epic, retold as poetry, is as intrinsically ennobling as any religious epic. (Edward O. Wilson)

Responding to this apparent overlap between cutting edge science and mystical experience, in recent years, there have been overt efforts to formulate religious belief systems that are built on truth claims based upon intersubjective verifiability, e.g. Anthroposophy, Yoism [5] .

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning philosophy. The field is related to many other branches of philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics.

Consensus reality is that which is generally agreed to be reality, based on a consensus view.

Phenomenology is the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness. As a philosophical movement it was founded in the early years of the 20th century by Edmund Husserl and was later expanded upon by a circle of his followers at the universities of Göttingen and Munich in Germany. It then spread to France, the United States, and elsewhere, often in contexts far removed from Husserl's early work.

Belief is the attitude that something is the case or true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to personal attitudes associated with true or false ideas and concepts. However, "belief" does not require active introspection and circumspection. For example, few ponder whether the sun will rise, just assume it will. Since "belief" is an important aspect of mundane life, according to Eric Schwitzgebel in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, a related question asks: "how a physical organism can have beliefs?"

Scientism is the promotion of science as the best or only objective means by which society should determine normative and epistemological values. The term scientism is generally used critically, implying a cosmetic application of science in unwarranted situations considered not amenable to application of the scientific method or similar scientific standards.

A worldview or world-view is the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge and point of view. A worldview can include natural philosophy; fundamental, existential, and normative postulates; or themes, values, emotions, and ethics.

Subjectivity is a central philosophical concept, related to consciousness, agency, personhood, reality, and truth, which has been variously defined by sources. Three common definitions include that subjectivity is the quality or condition of:

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and popular culture.

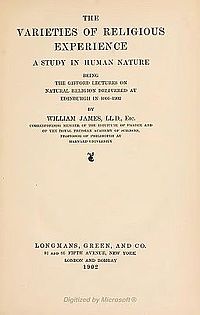

The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature is a book by Harvard University psychologist and philosopher William James. It comprises his edited Gifford Lectures on natural theology, which were delivered at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland between 1901 and 1902. The lectures concerned the psychological study of individual private religious experiences and mysticism, and used a range of examples to identify commonalities in religious experiences across traditions.

A religious experience is a subjective experience which is interpreted within a religious framework. The concept originated in the 19th century, as a defense against the growing rationalism of Western society. William James popularised the concept.

Intersubjectivity, in philosophy, psychology, sociology, and anthropology, is the psychological relation between people. It is usually used in contrast to solipsistic individual experience, emphasizing our inherently social being.

Lifeworld may be conceived as a universe of what is self-evident or given, a world that subjects may experience together. For Edmund Husserl, the lifeworld is the fundamental for all epistemological enquiries. The concept has its origin in biology and cultural Protestantism.

Positivism is a philosophical theory stating that certain ("positive") knowledge is based on natural phenomena and their properties and relations. Thus, information derived from sensory experience, interpreted through reason and logic, forms the exclusive source of all certain knowledge. Positivism holds that valid knowledge is found only in this a posteriori knowledge.

Language, Truth and Logic is a 1936 book by the philosopher by Alfred Jules Ayer. It brought some of the ideas of the Vienna Circle and the logical empiricists to the attention of the English-speaking world.

The problem of religious language considers whether it is possible to talk about God meaningfully if the traditional conceptions of God as being incorporeal, infinite, and timeless, are accepted. Because these traditional conceptions of God make it difficult to describe God, religious language has the potential to be meaningless. Theories of religious language either attempt to demonstrate that such language is meaningless, or attempt to show how religious language can still be meaningful.

Epistemology or theory of knowledge is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and scope (limitations) of knowledge. It addresses the questions "What is knowledge?", "How is knowledge acquired?", "What do people know?", "How do we know what we know?", and "Why do we know what we know?". Much of the debate in this field has focused on analyzing the nature of knowledge and how it relates to similar notions such as truth, belief, and justification. It also deals with the means of production of knowledge, as well as skepticism about different knowledge claims.

Phenomenology within sociology is the study of the formal structures of concrete social existence as made available in and through the analytical description of acts of intentional consciousness. The object of such an analysis is the meaningful lived world of everyday life: the Lebenswelt, or "Life-world". The task of phenomenological sociology, like that of every other phenomenological investigation, is to account for, or describe, the formal structures of this object of investigation in terms of subjectivity, as an object-constituted-in-and-for-consciousness. That which makes such a description different from the "naive" subjective descriptions of the man in the street, or those of the traditional social scientist, both operating in the natural attitude of everyday life, is the utilization of phenomenological methods.

In epistemology, criteria of truth are standards and rules used to judge the accuracy of statements and claims. They are tools of verification. Understanding a philosophy's criteria of truth is fundamental to a clear evaluation of that philosophy. This necessity is driven by the varying, and conflicting, claims of different philosophies. The rules of logic have no ability to distinguish truth on their own. An individual must determine what standards distinguish truth from falsehood. Not all criteria are equally valid. Some standards are sufficient, while others are questionable.

Eschatological verification describes a process whereby a proposition can be verified after death. A proposition such as "there is an afterlife" is verifiable if true but not falsifiable if false. The term is most commonly used in relation to God and the afterlife, although there may be other propositions - such as moral propositions - which may also be verified after death.

Postmodern religion is any type of religion that is influenced by postmodernism and postmodern philosophies. Examples of religions that may be interpreted using postmodern philosophy include Postmodern Christianity, Postmodern Neopaganism, and Postmodern Buddhism. Postmodern religion is not an attempt to banish religion from the public sphere; rather, it is a philosophical approach to religion that critically considers orthodox assumptions. Postmodern religious systems of thought view realities as plural, subjective, and dependent on the individual's worldview. Postmodern interpretations of religion acknowledge and value a multiplicity of diverse interpretations of truth, being, and ways of seeing. There is a rejection of sharp distinctions and global or dominant metanarratives in postmodern religion, and this reflects one of the core principles of postmodern philosophy. A postmodern interpretation of religion emphasises the key point that religious truth is highly individualistic, subjective, and resides within the individual.