In graph theory, an independent set, stable set, coclique or anticlique is a set of vertices in a graph, no two of which are adjacent. That is, it is a set of vertices such that for every two vertices in , there is no edge connecting the two. Equivalently, each edge in the graph has at most one endpoint in . A set is independent if and only if it is a clique in the graph's complement. The size of an independent set is the number of vertices it contains. Independent sets have also been called "internally stable sets", of which "stable set" is a shortening.

In graph theory, a perfect graph is a graph in which the chromatic number equals the size of the maximum clique, both in the graph itself and in every induced subgraph. In all graphs, the chromatic number is greater than or equal to the size of the maximum clique, but they can be far apart. A graph is perfect when these numbers are equal, and remain equal after the deletion of arbitrary subsets of vertices.

In graph theory, the perfect graph theorem of László Lovász states that an undirected graph is perfect if and only if its complement graph is also perfect. This result had been conjectured by Berge, and it is sometimes called the weak perfect graph theorem to distinguish it from the strong perfect graph theorem characterizing perfect graphs by their forbidden induced subgraphs.

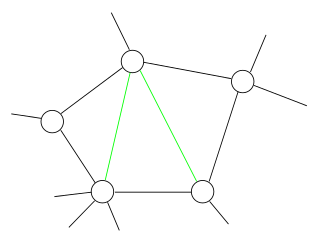

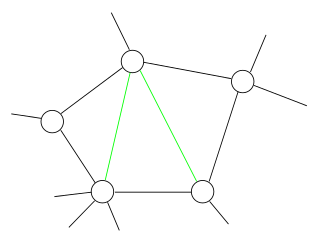

In the mathematical area of graph theory, a chordal graph is one in which all cycles of four or more vertices have a chord, which is an edge that is not part of the cycle but connects two vertices of the cycle. Equivalently, every induced cycle in the graph should have exactly three vertices. The chordal graphs may also be characterized as the graphs that have perfect elimination orderings, as the graphs in which each minimal separator is a clique, and as the intersection graphs of subtrees of a tree. They are sometimes also called rigid circuit graphs or triangulated graphs.

In graph theory, a cograph, or complement-reducible graph, or P4-free graph, is a graph that can be generated from the single-vertex graph K1 by complementation and disjoint union. That is, the family of cographs is the smallest class of graphs that includes K1 and is closed under complementation and disjoint union.

In graph theory, a clique graph of an undirected graph G is another graph K(G) that represents the structure of cliques in G.

In graph theory, a path decomposition of a graph G is, informally, a representation of G as a "thickened" path graph, and the pathwidth of G is a number that measures how much the path was thickened to form G. More formally, a path-decomposition is a sequence of subsets of vertices of G such that the endpoints of each edge appear in one of the subsets and such that each vertex appears in a contiguous subsequence of the subsets, and the pathwidth is one less than the size of the largest set in such a decomposition. Pathwidth is also known as interval thickness, vertex separation number, or node searching number.

In graph theory, an intersection graph is a graph that represents the pattern of intersections of a family of sets. Any graph can be represented as an intersection graph, but some important special classes of graphs can be defined by the types of sets that are used to form an intersection representation of them.

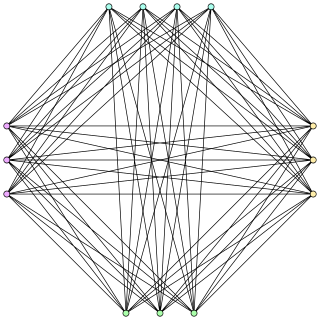

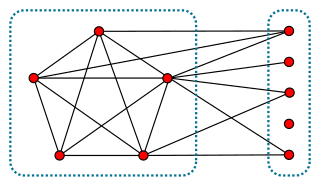

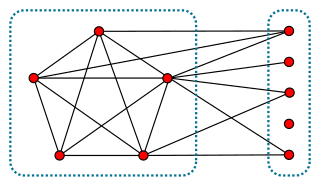

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, a split graph is a graph in which the vertices can be partitioned into a clique and an independent set. Split graphs were first studied by Földes and Hammer, and independently introduced by Tyshkevich and Chernyak (1979), where they called these graphs "polar graphs".

In graph theory, boxicity is a graph invariant, introduced by Fred S. Roberts in 1969.

In graph theory, a string graph is an intersection graph of curves in the plane; each curve is called a "string". Given a graph G, G is a string graph if and only if there exists a set of curves, or strings, such that the graph having a vertex for each curve and an edge for each intersecting pair of curves is isomorphic to G.

In graph theory, a branch of discrete mathematics, a distance-hereditary graph is a graph in which the distances in any connected induced subgraph are the same as they are in the original graph. Thus, any induced subgraph inherits the distances of the larger graph.

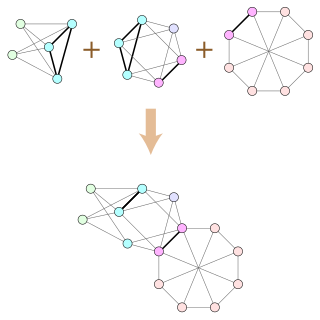

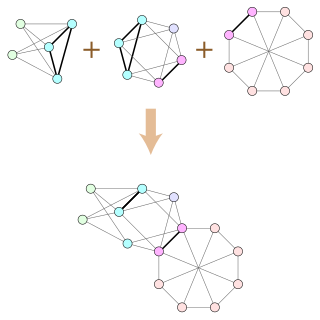

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, a clique sum is a way of combining two graphs by gluing them together at a clique, analogous to the connected sum operation in topology. If two graphs G and H each contain cliques of equal size, the clique-sum of G and H is formed from their disjoint union by identifying pairs of vertices in these two cliques to form a single shared clique, and then deleting all the clique edges or possibly deleting some of the clique edges. A k-clique-sum is a clique-sum in which both cliques have exactly k vertices. One may also form clique-sums and k-clique-sums of more than two graphs, by repeated application of the clique-sum operation.

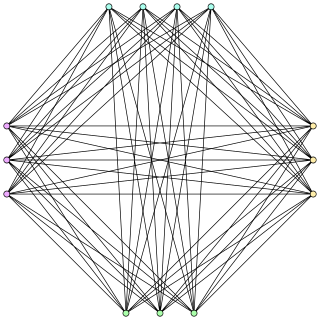

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a permutation graph is a graph whose vertices represent the elements of a permutation, and whose edges represent pairs of elements that are reversed by the permutation. Permutation graphs may also be defined geometrically, as the intersection graphs of line segments whose endpoints lie on two parallel lines. Different permutations may give rise to the same permutation graph; a given graph has a unique representation if it is prime with respect to the modular decomposition.

In graph theory, a trivially perfect graph is a graph with the property that in each of its induced subgraphs the size of the maximum independent set equals the number of maximal cliques. Trivially perfect graphs were first studied by but were named by Golumbic (1978); Golumbic writes that "the name was chosen since it is trivial to show that such a graph is perfect." Trivially perfect graphs are also known as comparability graphs of trees, arborescent comparability graphs, and quasi-threshold graphs.

In the mathematical area of graph theory, an undirected graph G is strongly chordal if it is a chordal graph and every cycle of even length in G has an odd chord, i.e., an edge that connects two vertices that are an odd distance (>1) apart from each other in the cycle.

In graph theory, a caterpillar or caterpillar tree is a tree in which all the vertices are within distance 1 of a central path.

In the mathematical field of graph theory, the intersection number of a graph is the smallest number of elements in a representation of as an intersection graph of finite sets. In such a representation, each vertex is represented as a set, and two vertices are connected by an edge whenever their sets have a common element. Equivalently, the intersection number is the smallest number of cliques needed to cover all of the edges of .

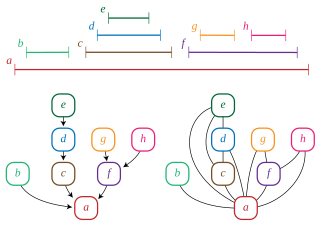

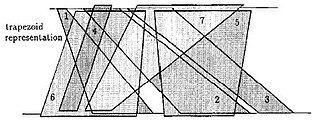

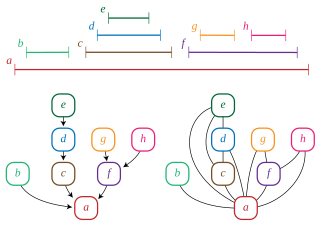

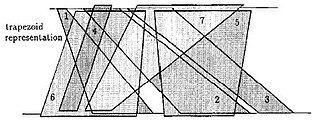

In graph theory, trapezoid graphs are intersection graphs of trapezoids between two horizontal lines. They are a class of co-comparability graphs that contain interval graphs and permutation graphs as subclasses. A graph is a trapezoid graph if there exists a set of trapezoids corresponding to the vertices of the graph such that two vertices are joined by an edge if and only if the corresponding trapezoids intersect. Trapezoid graphs were introduced by Dagan, Golumbic, and Pinter in 1988. There exists algorithms for chromatic number, weighted independent set, clique cover, and maximum weighted clique.

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, an indifference graph is an undirected graph constructed by assigning a real number to each vertex and connecting two vertices by an edge when their numbers are within one unit of each other. Indifference graphs are also the intersection graphs of sets of unit intervals, or of properly nested intervals. Based on these two types of interval representations, these graphs are also called unit interval graphs or proper interval graphs; they form a subclass of the interval graphs.