The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family—English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch, and Spanish—have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across several continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic; another nine subdivisions are now extinct.

Avestan is an umbrella term for two Old Iranian languages, Old Avestan and Younger Avestan. They are known only from their conjoined use as the scriptural language of Zoroastrianism; the Avesta serves as their namesake. Both are early Eastern Iranian languages within the Indo-Iranian language branch of the Indo-European language family. Its immediate ancestor was the Proto-Iranian language, a sister language to the Proto-Indo-Aryan language, with both having developed from the earlier Proto-Indo-Iranian language; as such, Old Avestan is quite close in both grammar and lexicon to Vedic Sanskrit, the oldest preserved Indo-Aryan language.

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated varieties may not be. This is a typical occurrence with widely spread languages and language families around the world, when these languages did not spread recently. Some prominent examples include the Indo-Aryan languages across large parts of India, varieties of Arabic across north Africa and southwest Asia, the Turkic languages, the Chinese languages or dialects, and parts of the Romance, Germanic and Slavic families in Europe. Terms used in older literature include dialect area and L-complex.

The Moabite language, also known as the Moabite dialect, is an extinct sub-language or dialect of the Canaanite languages, themselves a branch of Northwest Semitic languages, formerly spoken in the region described in the Bible as Moab in the early 1st millennium BC.

The La Spezia–Rimini Line, in the linguistics of the Romance languages, is a line that demarcates a number of important isoglosses that distinguish Romance languages south and east of the line from Romance languages north and west of it. The line runs through northern Italy, very roughly from the cities of La Spezia to Rimini. Romance languages on the eastern half of it include Italian and the Eastern Romance languages, whereas Catalan, French, Occitan, Portuguese, Romansh, Spanish, and the Gallo‒Italic languages are representatives of the Western group. Sardinian does not fit into either Western or Eastern Romance.

Old South Arabian (also known as Ancient South Arabian (ASA), Epigraphic South Arabian, Ṣayhadic, or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages (Sabaean/Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramitic, Minaic) spoken in the far southern portion of the Arabian Peninsula. The earliest preserved records belonging to the group are dated to the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE. They were written in the Ancient South Arabian script.

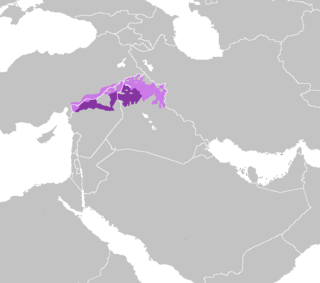

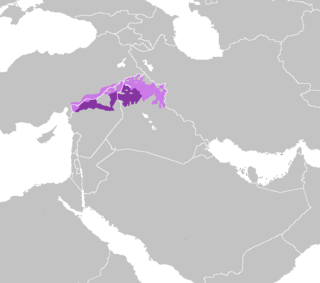

Median was the language of the Medes. It is an ancient Iranian language and classified as belonging to the Northwestern Iranian subfamily, which includes many other languages such as Kurdish, Old Azeri, Talysh, Gilaki, Mazandarani, Zaza–Gorani and Baluchi.

Mesopotamian Arabic or Iraqi Arabic is a group of varieties of Arabic spoken in the Mesopotamian basin of Iraq, as well as in Syria, Kuwait, southeastern Turkey, Iran, and Iraqi diaspora communities.

The Iranian languages, also called the Iranic languages, are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family that are spoken natively by the Iranian peoples, predominantly in the Iranian Plateau.

As the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) broke up, its sound system diverged as well, as evidenced in various sound laws associated with the daughter Indo-European languages.

Proto-Albanian is the ancestral reconstructed language of Albanian, before the Gheg–Tosk dialectal diversification. Albanoid and other Paleo-Balkan languages had their formative core in the Balkans after the Indo-European migrations in the region. Whether descendants or sister languages of what was called Illyrian by classical sources, Albanian and Messapic, on the basis of shared features and innovations, are grouped together in a common branch in the current phylogenetic classification of the Indo-European language family. The precursor of Albanian can be considered a completely formed independent IE language since at least the first millennium BCE, with the beginning of the early Proto-Albanian phase.

The term Thraco-Illyrian refers to a hypothesis according to which the Daco-Thracian and Illyrian languages comprise a distinct branch of Indo-European. Thraco-Illyrian is also used as a term merely implying a Thracian-Illyrian interference, mixture or sprachbund, or as a shorthand way of saying that it is not determined whether a subject is to be considered as pertaining to Thracian or Illyrian. Downgraded to a geo-linguistic concept, these languages are referred to as Paleo-Balkan.

The linguistic classification of the ancient Thracian language has long been a matter of contention and uncertainty, and there are widely varying hypotheses regarding its position among other Paleo-Balkan languages. It is not contested, however, that the Thracian languages were Indo-European languages which had acquired satem characteristics by the time they are attested.

Proto-Iranian or Proto-Iranic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Iranian languages branch of Indo-European language family and thus the ancestor of the Iranian languages such as Persian, Pashto, Sogdian, Zazaki, Ossetian, Mazandarani, Kurdish, Talysh and others. Its speakers, the hypothetical Proto-Iranians, are assumed to have lived in the 2nd millennium BC and are usually connected with the Andronovo archaeological horizon.

North Mesopotamian Arabic, also known as Moslawi, Mardelli, Mesopotamian Qeltu Arabic, or Syro-Mesopotamian Arabic, is one of the two main varieties of Mesopotamian Arabic, together with Gilit Mesopotamian Arabic.

Albrecht Ernst Rudolf Goetze was a German-American Hittitologist.

Israelian Hebrew is a northern dialect of biblical Hebrew (BH) proposed as an explanation for various irregular linguistic features of the Masoretic Text (MT) of the Hebrew Bible. It competes with the alternative explanation that such features are Aramaisms, indicative either of late dates of composition, or of editorial emendations. Although IH is not a new proposal, it only started gaining ground as a challenge to older arguments to late dates for some biblical texts since about a decade before the turn of the 21st century: linguistic variation in the Hebrew Bible might be better explained by synchronic rather than diachronic linguistics, meaning various biblical texts could be significantly older than many 20th century scholars supposed.

Languages of the Indo-European family are classified as either centum languages or satem languages according to how the dorsal consonants of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) developed. An example of the different developments is provided by the words for "hundred" found in the early attested Indo-European languages. In centum languages, they typically began with a sound, but in satem languages, they often began with.

PalatalizationPA-lə-tə-leye-ZAY-shən is a historical-linguistic sound change that results in a palatalized articulation of a consonant or, in certain cases, a front vowel. Palatalization involves change in the place or manner of articulation of consonants, or the fronting or raising of vowels. In some cases, palatalization involves assimilation or lenition.

Taymanitic was the language and script of the oasis of Taymāʾ in northwestern Arabia, dated to the second half of the 6th century BC.