Francesco I Sforza was an Italian condottiero who founded the Sforza dynasty in the duchy of Milan, ruling as its (fourth) duke from 1450 until his death.

The House of Sforza was a ruling family of Renaissance Italy, based in Milan. Sforza rule began with the family's acquisition of the Duchy of Milan following the extinction of the Visconti family in the mid-15th century and ended with the death of the last member of the family's main branch, Francesco II Sforza, in 1535.

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici was an Italian banker and politician who established the Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derived from his wealth as a banker and intermarriage with other rich and powerful families. He was a patron of arts, learning, and architecture. He spent over 600,000 gold florins on art and culture, including Donatello's David, the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity.

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the Valois kings of France, and their Habsburg opponents in the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. At different points, various Italian states participated in the war, some on both sides, with limited involvement from England and the Ottoman Empire.

The Republic of Florence, known officially as the Florentine Republic, was a medieval and early modern state that was centered on the Italian city of Florence in Tuscany, Italy. The republic originated in 1115, when the Florentine people rebelled against the Margraviate of Tuscany upon the death of Matilda of Tuscany, who controlled vast territories that included Florence. The Florentines formed a commune in her successors' place. The republic was ruled by a council known as the Signoria of Florence. The signoria was chosen by the gonfaloniere, who was elected every two months by Florentine guild members.

Piero di Cosimo de' Medici, known as Piero the Gouty, was the de facto ruler of Florence from 1464 to 1469, during the Italian Renaissance.

Condottieri were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other European monarchs during the Italian Wars of the Renaissance and the European Wars of Religion. Notable condottieri include Prospero Colonna, Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, Cesare Borgia, the Marquis of Pescara, Andrea Doria, and the Duke of Parma.

Federico da Montefeltro, also known as Federico III da Montefeltro KG, was one of the most successful mercenary captains (condottieri) of the Italian Renaissance, and lord of Urbino from 1444 until his death. A renowned intellectual humanist and civil leader in Urbino on top of his impeccable reputation for martial skill and honour, he commissioned the construction of a great library, perhaps the largest of Italy after the Vatican, with his own team of scribes in his scriptorium, and assembled around him a large humanistic court in the Ducal Palace, Urbino, designed by Luciano Laurana and Francesco di Giorgio Martini.

Niccolò Piccinino was an Italian condottiero.

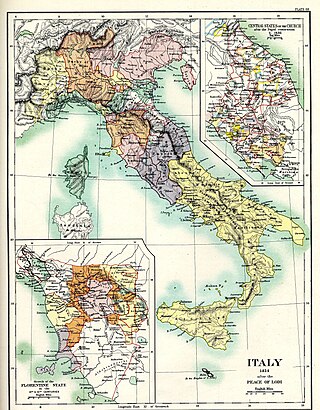

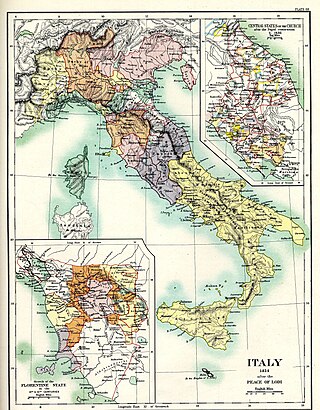

The Treaty of Lodi, or Peace of Lodi, was a peace agreement to put an end to the Wars in Lombardy between the Venetian Republic and the Duchy of Milan, signed in the city of Lodi on 9 April 1454.

Galeazzo Maria Sforza was the fifth Duke of Milan from 1466 until 1476. He was notorious for being lustful, cruel, and tyrannical.

Caterina Sforza was an Italian noblewoman, the Countess of Forlì and Lady of Imola, firstly with her husband Girolamo Riario, and after his death as a regent of her son Ottaviano.

The Golden Ambrosian Republic was a short-lived republic founded in Milan by members of the University of Pavia with popular support, during the first phase of the Milanese War of Succession. With the aid of Francesco Sforza they held out against the forces of the Republic of Venice, but after a betrayal Sforza defected and captured Milan to become Duke himself, abolishing the Republic.

The First Italian War, or Charles VIII's Italian War, was the opening phase of the Italian Wars. The war pitted Charles VIII of France, who had initial Milanese aid, against the Holy Roman Empire, Spain and an alliance of Italian powers led by Pope Alexander VI, known as the League of Venice.

The Italian Wars of 1499–1504 are divided into two connected, but distinct phases: the Second Italian War (1499–1501), sometimes known as Louis XII's Italian War, and the Third Italian War (1502–1504) or War over Naples. The first phase was fought for control of the Duchy of Milan by an alliance of Louis XII of France and the Republic of Venice against Ludovico Sforza, the second between Louis and Ferdinand II of Aragon for possession of the Kingdom of Naples.

The War of Ferrara was fought in 1482–1484 between Ercole I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, and the Papal forces mustered by Ercole's personal nemesis, Pope Sixtus IV and his Venetian allies. Hostilities ended with the Treaty of Bagnolo, signed on 7 August 1484.

The Wars in Lombardy were a series of conflicts between the Republic of Venice and the Duchy of Milan and their respective allies, fought in four campaigns in a struggle for hegemony in Northern Italy that ravaged the economy of Lombardy. They lasted from 1423 until the signing of the Treaty of Lodi in 1454. During their course, the political structure of Italy was transformed: out of a competitive congeries of communes and city-states emerged the five major Italian territorial powers that would make up the map of Italy for the remainder of the 15th century and the beginning of the Italian Wars at the turn of the 16th century. They were Venice, Milan, Florence, the Papal States and Naples. Important cultural centers of Tuscany and Northern Italy—Siena, Pisa, Urbino, Mantua, Ferrara—became politically marginalized.

This timeline lists important events relevant to the life of the Italian diplomat, writer and political philosopher Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (1469–1527).

The Milanese War of Succession was a war of succession over the Duchy of Milan from the death of duke Filippo Maria Visconti on 13 August 1447 to the Treaty of Lodi on 9 April 1454.