Related Research Articles

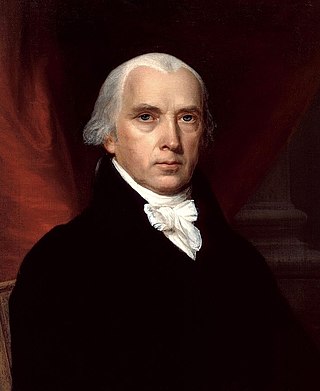

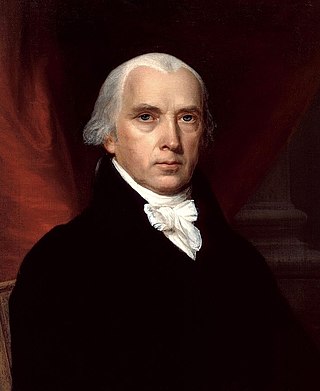

James Madison was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

James Monroe was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party. He was the last Founding Father to serve as president as well as the last president of the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation. His presidency coincided with the Era of Good Feelings, concluding the First Party System era of American politics. He issued the Monroe Doctrine, a policy of limiting European colonialism in the Americas. Monroe previously served as governor of Virginia, a member of the United States Senate, U.S. ambassador to France and Britain, the seventh secretary of state, and the eighth secretary of war.

Thomas Jefferson was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. Following the American Revolutionary War and prior to becoming president in 1801, Jefferson was the nation's first U.S. secretary of state under George Washington and then the nation's second vice president under John Adams.

Dolley Todd Madison was the wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She was noted for holding Washington social functions in which she invited members of both political parties, essentially spearheading the concept of bipartisan cooperation. Previously, founders such as Thomas Jefferson would only meet with members of one party at a time, and politics could often be a violent affair resulting in physical altercations and even duels. Madison helped to create the idea that members of each party could amicably socialize, network, and negotiate with each other without violence. By innovating political institutions as the wife of James Madison, Dolley Madison did much to define the role of the President's spouse, known only much later by the title first lady—a function she had sometimes performed earlier for the widowed Thomas Jefferson.

George Mason was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including substantial portions of the Fairfax Resolves of 1774, the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, and his Objections to this Constitution of Government (1787) opposing ratification, have exercised a significant influence on American political thought and events. The Virginia Declaration of Rights, which Mason principally authored, served as a basis for the United States Bill of Rights, of which he has been deemed a father.

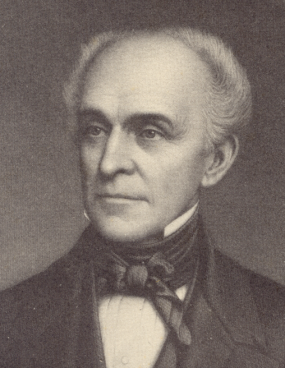

Edward Coles was an American planter and politician, elected as the second Governor of Illinois. From an old Virginia family, Coles as a young man was a neighbor and associate of presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, as well as, secretary to President James Madison from 1810 to 1815.

James Madison's Montpelier, located in Orange County, Virginia, was the plantation house of the Madison family, including Founding Father and fourth president of the United States James Madison and his wife, Dolley. The 2,650-acre (1,070 ha) property is open seven days a week with the mission of engaging the public with the enduring legacy of Madison's most powerful idea: government by the people.

James Madison Sr. was a prominent Virginia planter and politician who served as a colonel in the Virginia militia during the American Revolutionary War. He inherited Mount Pleasant, later known as Montpelier, a large tobacco plantation in Orange County, Virginia and, with the acquisition of more property, had 5,000 acres and became the largest landowner in the county. He was the father of James Madison Jr., the 4th president of the United States, who inherited what he called Montpelier, and Lieutenant General William Taylor Madison, and great-grandfather of Confederate Brigadier General James Edwin Slaughter.

The presidency of James Madison began on March 4, 1809, when James Madison was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1817. Madison, the fourth United States president, took office after defeating Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney decisively in the 1808 presidential election. He was re-elected four years later, defeating DeWitt Clinton in the 1812 election. His presidency was dominated by the War of 1812 with Britain. After serving two terms as president, Madison was succeeded in 1817 by James Monroe, his Secretary of State and a fellow member of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Ambrose Madison was an American planter and politician in the Piedmont of Virginia Colony. He married Frances Taylor in 1721, daughter of James Taylor, a member of the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition across the Blue Ridge Mountains from the Tidewater. Through her father, Madison and his brother-in-law Thomas Chew were aided in acquiring 4,675 acres in 1723, in what became Orange County. There he developed his tobacco plantation known as Mount Pleasant The Madisons were parents of James Madison Sr. and paternal grandparents of President James Madison.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

Paul Jennings (1799–1874) was an American abolitionist and author. Enslaved as a young man by President James Madison during and after his White House years, Jennings published, in 1865, the first White House memoir. His book was A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison, described as "a singular document in the history of slavery and the early American republic."

John Payne Todd, was an American secretary. He was the first son of Dolley Payne and John Todd Jr. His father and younger brother died in the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic, which killed nearly 10 percent of the city's population. His mother remarried the following year, to the older James Madison, the future president of the United States.

William du Pont Jr. was an English-born American businessman and banker, and a prominent figure in the sport of Thoroughbred horse racing. He developed and designed more than 20 racing venues, including Fair Hill at his 5,000-acre estate in Maryland. A member of the Delaware Du Pont family, he was the son of William du Pont and Annie Rogers Zinn, and brother to Marion duPont Scott, a noted horsewoman and breeder.

This bibliography of James Madison is a list of published works about James Madison, the 4th president of the United States.

William Gardner was an enslaved man born into the family of James Madison in Montpelier, Virginia, to a man likely named Tony. Madison's father gave Gardner to the young Madison as a companion when Madison was a child.

Mary Estelle Elizabeth Cutts was an American socialite, amateur historian, and memoirist. She exchanged letters frequently with Dolley Madison and, after Madison's death in 1849, spent the last seven years of her life writing and attempting to publish two memoirs. The memoirs included biographical information on Madison and were published in 1886 as the heavily edited Memoirs and Letters of Dolley Madison, Wife of James Madison, President of the United States by Lucia B. Cutts. The work was the standard on Madison's life for over a century.

James Madison was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the 4th president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. He is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights. Disillusioned by the weak national government established by the Articles of Confederation, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution. Madison's Virginia Plan served as the basis for the Constitutional Convention's deliberations, and he was one of the most influential individuals at the convention. He became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution, and he joined with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays that was one of the most influential works of political science in American history.

Eleanor "Nelly" Rose Madison was a prominent Virginia socialite and planter who was the mother of James Madison Jr., the 4th president of the United States and Lieutenant General William Taylor Madison. She has been described as one of the strongest female influences in the life of James Madison Jr., and has been credited for her efforts to preserve the Montpelier estate.

References

- ↑ Burstein & Isenberg 2010 , pp. 26, 200–202

- ↑ "Madison, James and Slavery – Encyclopedia Virginia".

- 1 2 3 "James Madison and Slavery".

- ↑ Burstein & Isenberg 2010 , pp. 162–163

- ↑ Burstein & Isenberg 2010 , pp. 156–157

- 1 2 Guyatt, Nicholas (June 6, 2019). "How Proslavery Was the Constitution?". New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Burstein & Isenberg 2010 , pp. 200–201

- ↑ Burstein & Isenberg 2010 , pp. 607–608

- 1 2 Watts 1990, p. 1289.

- ↑ Ketcham 2002, p. 57.

- ↑ Broadwater 2012, pp. 188–189.

- 1 2 Broadwater 2012, p. 188.

- 1 2 3 4 "Visit to Montpelier, Home of Madison". The Cincinnati Enquirer. 1879-04-07. p. 5. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- 1 2 Hopkins 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Crew of Negroes". Virginian-Pilot. 1901-01-16. p. 6. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ↑ "Paul Jennings – Enamoured with Freedom". www.montepelier.org. The Montpelier Foundation. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)