Related Research Articles

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg, born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a Prussian and later German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of Junker landowners, Bismarck rose rapidly in Prussian politics, and from 1862 to 1890 he was the minister president and foreign minister of Prussia. Before his rise to the executive, he was the Prussian ambassador to Russia and France and served in both houses of the Prussian parliament. He masterminded the unification of Germany in 1871, and served as the first chancellor of the German Empire until 1890, in which capacity he dominated European affairs. He had served as chancellor of the North German Confederation from 1867 to 1871, alongside his responsibilities in the Kingdom of Prussia. He cooperated with King Wilhelm I of Prussia to unify the various German states, a partnership that would last for the rest of Wilhelm's life. The King granted Bismarck the titles of Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen in 1865 and Prince of Bismarck in 1871. Bismarck provoked three short, decisive wars against Denmark, Austria, and France. Following the victory against Austria, he abolished the supranational German Confederation and instead formed the North German Confederation as the first German national state, aligning the smaller North German states behind Prussia, while excluding Austria. Receiving the support of the independent South German states in the Confederation's defeat of France, he formed the German Empire – which also excluded Austria – and united Germany.

The German Democratic Party was a liberal political party in the Weimar Republic, considered centrist or centre-left. Along with the right-liberal German People's Party, it represented political liberalism in Germany between 1918 and 1933. It was formed in 1918 from the Progressive People's Party and the liberal wing of the National Liberal Party, both of which had been active in the German Empire.

Kulturkampf was a fierce conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues were clerical control of education and ecclesiastical appointments. A unique feature of Kulturkampf, compared to other struggles between the state and the Catholic Church in other countries, was Prussia's anti-Polish component. By extension the term Kulturkampf is sometimes used to describe any conflict between secular and religious authorities or deeply opposing values, beliefs between sizable factions within a nation, community, or other group.

The Centre Party, officially the German Centre Party and also known in English as the Catholic Centre Party, is a Christian democratic and Catholic political party in Germany. Influential in the German Empire and Weimar Republic, it is the oldest German political party in existence. Formed in 1870, it successfully battled the Kulturkampf waged by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck against the Catholic Church. It soon won a quarter of the seats in the Reichstag, and its middle position on most issues allowed it to play a decisive role in the formation of majorities. The party name Zentrum (Centre) originally came from the fact that Catholic representatives would take up the middle section of seats in parliament between the social democrats and the conservatives.

The National Liberal Party was a liberal party of the North German Confederation and the German Empire which flourished between 1867 and 1918.

Eduard Lasker was a German politician and jurist. Inspired by the French Revolution, he became a spokesman for liberalism and the leader of the left wing of the National Liberal party, which represented middle-class professionals and intellectuals. He promoted the unification of Germany during the 1860s and played a major role in codification of the German legal code. Lasker at first compromised with Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who later strenuously opposed Lasker regarding freedom of the press. In 1881, Lasker left the National Liberal party and helped form the new German Free Thought Party.

State Socialism was a set of social programs implemented in the German Empire that were initiated by Otto von Bismarck in 1883 as remedial measures to appease the working class and detract support for socialism and the Social Democratic Party of Germany following earlier attempts to achieve the same objective through Bismarck's Anti-Socialist Laws. As a term, it was coined by Bismarck's liberal opposition to these social welfare policies, but it was later accepted by Bismarck. This did not prevent the Social Democrats from becoming the biggest party in the Reichstag by 1912. According to historian Jonathan Steinberg, "[a]ll told, Bismarck's system was a massive success—except in one respect. His goal to keep the Social Democratic Party out of power utterly failed. The vote for the Social Democratic Party went up and by 1912 they were the biggest party in the Reichstag".

Baron Ludwig von Windthorst was a German politician and leader of the Catholic Centre Party and the most notable opponent of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck during the Prussian-led unification of Germany and the Kulturkampf. Margaret L. Anderson argues that he was "Imperial Germany's greatest parliamentarian" and bears comparison with Irishmen Daniel O'Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell "in his handling of party machinery and his relation to the masses."

Friedrich Karl Biedermann was a German professor, politician, and publisher who greatly aided the Liberal movement in Germany during the process of German Unification.

The German Progress Party was the first modern political party in Germany, founded by liberal members of the Prussian House of Representatives in 1861 in opposition to Minister President Otto von Bismarck.

The German People's Party was a German liberal party created in 1868 by the wing of the German Progress Party which during the conflict about whether the unification of Germany should be led by the Kingdom of Prussia or Austria-Hungary supported Austria. The party was most popular in Southern Germany.

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was passed on 19 October 1878 by the Reichstag lasting until 31 March 1881 and extended four times.

Wilhelm Hasenclever was a German politician. He was originally a tanner by trade but later became a journalist and author. However, he is most known for his political work in the predecessors of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

Conservatism in Germany has encompassed a wide range of theories and ideologies in the last three hundred years, but most historical conservative theories supported the monarchical/hierarchical political structure.

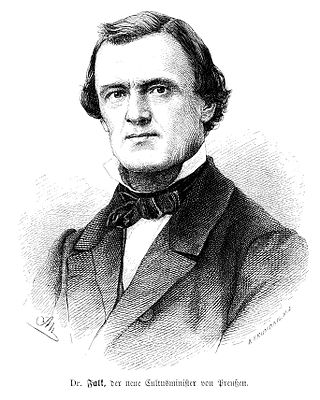

The Falk Laws or May Laws of 1873–1875 were legislative bills enacted in the German Kingdom of Prussia during the Kulturkampf conflict with the Catholic Church. They were named after Adalbert Falk, the Prussian Minister of Culture (1872–1879).

The Reichstag Peace Resolution passed by the Reichstag of the German Empire on 19 July 1917 was an attempt to seek a negotiated peace treaty to end World War I. The resolution called for no annexations, no indemnities, freedom of the seas and international arbitration. Although it was rejected by the German High Command and the Allied powers and thus had no effect on the progress of the war, it helped shape internal German politics by bringing the moderate parties that supported the resolution into a group that would shape much of the Weimar Republic's politics. The conservative parties that opposed the resolution were those that tended to be hostile to the republic.

The Reichstag of the German Empire was Germany's lower House of Parliament from 1871 to 1918. Within the governmental structure of the Reich, it represented the national and democratic element alongside the federalism of the Bundesrat and the monarchic and bureaucratic element of the executive, embodied in the Reich chancellor. Together with the Bundesrat, the Reichstag had legislative power and shared in decision-making on the Reich budget. It also had certain rights of control over the executive branch and could engage the public through its debates. The emperor had little political power, and over time the position of the Reichstag strengthened with respect to the Bundesrat.

The Liberal Union was a short-lived liberal party in the German Empire. It originated in 1880 as a breakaway from the National Liberal Party and so was also called the Secession. It merged with the left liberal German Progress Party to form the German Free-minded Party in 1884.

The Reichstag of the North German Confederation was the federal state's lower house of parliament. The popularly elected Reichstag was responsible for federal legislation together with the Bundesrat, the upper house whose members were appointed by the governments of the individual states to represent their interests. Executive power lay with the Bundesrat and the king of Prussia acting as Bundespräsidium, or head of state. The Reichstag debated and approved or rejected taxes and expenditures and could propose laws in its own right. To become effective, all laws required the approval of both the Bundesrat and the Reichstag. Voting rights in Reichstag elections were advanced for the time, granting universal, equal, and secret suffrage to men above the age of 25.

The Bund der Landwirte (BDL) was a German advocacy group founded 18 February 1893 by farmers and agricultural interests in response to the farm crisis of the 1890s, and more specifically the result of the protests against the low-tariff policies of Chancellor Leo von Caprivi, including his free trade policies.

References

- ↑ William I (first signatory); Otto von Bismarck (second signatory) (4 July 1872). "Gesetz, betreffend den Orden der Gesellschaft Jesu". Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt (in German). Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt 1872. p. 253. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Reinhold Zippelius: Staat und Kirche. C. H. Beck, München 1997.

- ↑ "Band 4. Reichsgründung: Bismarcks Deutschland : 1866-1890 Das „Jesuitengesetz" (4. Juli 1872) ..... Der Begriff Kulturkampf wurde von dem deutschen Pathologen und liberalen Politiker Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902) geprägt, um das Ringen zwischen der katholischen Kirche und dem preußischen Staat zu beschreiben. Kurz nach der deutschen Einigung 1871 leiteten Bismarck und..." (PDF). Reichsgesetzblatt, 1872, S. 253, Abgedruckt in Ernst Rudolf Huber, Hg., Dokumente zur Deutschen Verfassungsgeschichte, 3. bearb. Aufl., Bd. 2, 1851-1900. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1986, p. 461 (in German). The German Historical Institute, Washington DC (German History in Documents and Images (GHDI)). Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Reichstagsprotokolle, 1872, S.1149-1150.

- ↑ Karl Biedermann (12 June 1872). "Karl Biedermann to Eduard Lasker, Agonizing over Liberalism's Stance on Exceptional Laws (June 12, 1872)". Forging an Empire: Bismarckian Germany (1866-1890) .... Documents - Politics II: Parties and Political Mobilization. The German Historical Institute, Washington DC (German History in Documents and Images (GHDI)): Original German text reprinted in Julius Heyderhoff and Paul Wentzcke, eds, Deutscher Liberalismus im Zeitalter Bismarcks. Eine politische Briefsammlung [German Liberalism in Bismarck's Era: A Collection of Political Letters], 2 vols., vol. 2, Im neuen Reich, 1871-1890. Politische Briefe aus dem Nachlaß liberaler Parteiführer [In the New Reich 1871-1890. Political Letters from the Private Papers of Liberal Party Leaders], ed. Paul Wentzcke. Bonn, Leipzig: Kurt Schroeder Verlag, 1926, pp. 53-54. Translation: Erwin Fink. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter (quoting Bismarck) (2007). "Canossa – Sieg der Moral? Mit dem legendären Gang Heinrichs IV. begann die Entzauberung der Welt". '"Seien Sie außer Sorge, nach Canossa gehen wir nicht – weder körperlich noch geistig."' (in German). Universität Heidelberg. Retrieved 26 July 2015.