The United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), also called the FISA Court, is a U.S. federal court established under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA) to oversee requests for surveillance warrants against foreign spies inside the United States by federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and processing of information and data for foreign and domestic intelligence and counterintelligence purposes, specializing in a discipline known as signals intelligence (SIGINT). The NSA is also tasked with the protection of U.S. communications networks and information systems. The NSA relies on a variety of measures to accomplish its mission, the majority of which are clandestine. The NSA has roughly 32,000 employees.

The state secrets privilege is an evidentiary rule created by United States legal precedent. Application of the privilege results in exclusion of evidence from a legal case based solely on affidavits submitted by the government stating that court proceedings might disclose sensitive information which might endanger national security. United States v. Reynolds, which involved alleged military secrets, was the first case that saw formal recognition of the privilege.

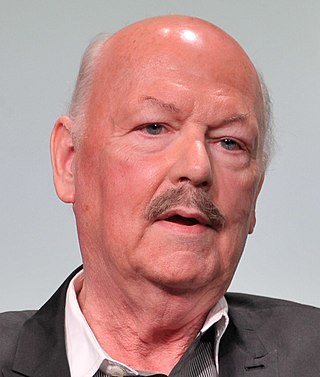

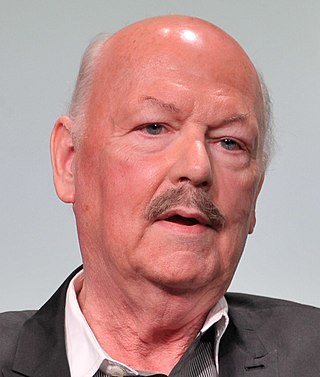

James Bamford is an American author, journalist and documentary producer noted for his writing about United States intelligence agencies, especially the National Security Agency (NSA). The New York Times has called him "the nation's premier journalist on the subject of the National Security Agency" and The New Yorker named him "the NSA's chief chronicler."

NSA warrantless surveillance — also commonly referred to as "warrantless-wiretapping" or "-wiretaps" — was the surveillance of persons within the United States, including U.S. citizens, during the collection of notionally foreign intelligence by the National Security Agency (NSA) as part of the Terrorist Surveillance Program. In late 2001, the NSA was authorized to monitor, without obtaining a FISA warrant, phone calls, Internet activities, text messages and other forms of communication involving any party believed by the NSA to be outside the U.S., even if the other end of the communication lays within the U.S.

American Civil Liberties Union v. National Security Agency, 493 F.3d 644, is a case decided July 6, 2007, in which the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held that the plaintiffs in the case did not have standing to bring the suit against the National Security Agency (NSA), because they could not present evidence that they were the targets of the so-called "Terrorist Surveillance Program" (TSP).

The Terrorist Surveillance Program was an electronic surveillance program implemented by the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks. It was part of the President's Surveillance Program, which was in turn conducted under the overall umbrella of the War on Terrorism. The NSA, a signals intelligence agency, implemented the program to intercept al Qaeda communications overseas where at least one party is not a U.S. person. In 2005, The New York Times disclosed that technical glitches resulted in some of the intercepts including communications which were "purely domestic" in nature, igniting the NSA warrantless surveillance controversy. Later works, such as James Bamford's The Shadow Factory, described how the nature of the domestic surveillance was much, much more widespread than initially disclosed. In a 2011 New Yorker article, former NSA employee Bill Binney said that his colleagues told him that the NSA had begun storing billing and phone records from "everyone in the country."

Hepting v. AT&T, 439 F.Supp.2d 974, was a class action lawsuit argued before the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, filed by Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) on behalf of customers of the telecommunications company AT&T. The plaintiffs alleged that AT&T permitted and assisted the National Security Agency (NSA) in unlawfully monitoring the personal communications of American citizens, including AT&T customers, whose communications were routed through AT&T's network.

MAINWAY is a database maintained by the United States' National Security Agency (NSA) containing metadata for hundreds of billions of telephone calls made through the largest telephone carriers in the United States, including AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile.

Room 641A is a telecommunication interception facility operated by AT&T for the U.S. National Security Agency, as part of its warrantless surveillance program as authorized by the Patriot Act. The facility commenced operations in 2003 and its purpose was publicly revealed in 2006.

EPIC v. Department of Justice is a 2014 case in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia between the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) where EPIC seeks court action to enforce their Freedom of Information Act request for documents that the Department of Justice has withheld pertaining to George W. Bush's authorization of NSA warrantless surveillance.

Al-Haramain v. Obama, 690 F.3d 1089 was a case before the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California filed 28 February 2006 by the al-Haramain Foundation and its two attorneys concerning the NSA warrantless surveillance controversy. The case withstood retroactive changes brought by the Congressional response to the NSA warrantless surveillance program.

Clapper v. Amnesty International USA, 568 U.S. 398 (2013), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that Amnesty International USA and others lacked standing to challenge section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, as amended by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 Amendments Act of 2008.

The practice of mass surveillance in the United States dates back to wartime monitoring and censorship of international communications from, to, or which passed through the United States. After the First and Second World Wars, mass surveillance continued throughout the Cold War period, via programs such as the Black Chamber and Project SHAMROCK. The formation and growth of federal law-enforcement and intelligence agencies such as the FBI, CIA, and NSA institutionalized surveillance used to also silence political dissent, as evidenced by COINTELPRO projects which targeted various organizations and individuals. During the Civil Rights Movement era, many individuals put under surveillance orders were first labelled as integrationists, then deemed subversive, and sometimes suspected to be supportive of the communist model of the United States' rival at the time, the Soviet Union. Other targeted individuals and groups included Native American activists, African American and Chicano liberation movement activists, and anti-war protesters.

Klayman v. Obama, 957 F.Supp.2d 1, was a decision by the United States District Court for District of Columbia finding that the National Security Agency's (NSA) bulk phone metadata collection program was unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment. The ruling was later overturned on jurisdictional grounds, leaving the constitutional implications of NSA surveillance unaddressed.

American Civil Liberties Union v. Clapper, 785 F.3d 787, was a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and its affiliate, the New York Civil Liberties Union, against the United States federal government as represented by then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper. The ACLU challenged the legality and constitutionality of the National Security Agency's (NSA) bulk phone metadata collection program.

Litigation over global surveillance has occurred in multiple jurisdictions since the global surveillance disclosures of 2013.

Wikimedia Foundation, et al. v. National Security Agency, et al. is a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) on behalf of the Wikimedia Foundation and several other organizations against the National Security Agency (NSA), the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), and other named individuals, alleging mass surveillance of Wikipedia users carried out by the NSA. The suit claims the surveillance system, which NSA calls "Upstream", breaches the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which protects freedom of speech, and the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures.

Wolf v. Vidal, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a case that was filed to challenge the Trump Administration's rescission of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Plaintiffs in the case are DACA recipients who argue that the rescission decision is unlawful under the Administrative Procedure Act and the Fifth Amendment. On February 13, 2018, Judge Garaufis in the Eastern District of New York addressed the question of whether the government offered a legally adequate reason for ending the DACA program. The court found that Defendants did not provide a legally adequate reason for ending the DACA program and that the decision to end DACA was arbitrary and capricious. Defendants have appealed the decision to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

Halkin v. Helms is a landmark 1978 United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit case concerning the State secrets privilege.