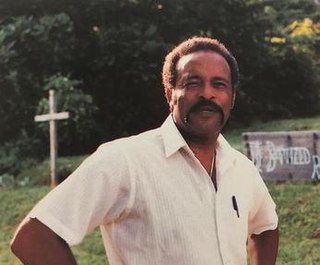

Lonnie Bradley Holley, sometimes known as the Sand Man, is an American artist, art educator, and musician. He is best known for his assemblages and immersive environments made of found materials. In 1981, after he brought a few of his sandstone carvings to then-Birmingham Museum of Art director Richard Murray, the latter helped to promote his work. In addition to solo exhibitions at the Birmingham Museum of Art and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston, Holley has exhibited in group exhibitions with other Black artists from the American South at the Michael C. Carlos Museum and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, Pérez Art Museum Miami, NSU Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, de Young Museum in San Francisco, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England, and the Royal Academy of Arts in London, among other places.

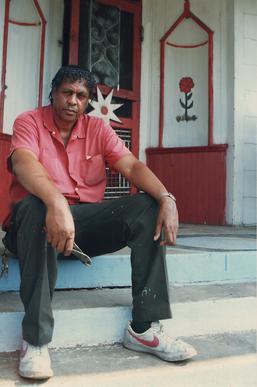

Thornton Dial was a pioneering American artist who came to prominence in the late 1980s. Dial's body of work exhibits formal variety through expressive, densely composed assemblages of found materials, often executed on a monumental scale. His range of subjects embraces a broad sweep of history, from human rights to natural disasters and current events. Dial's works are widely held in American museums; ten of Dial's works were acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2014.

Nellie Mae Rowe was an African-American artist from Fayette County, Georgia. Although she is best known today for her colorful works on paper, Rowe worked across mediums, creating drawings, collages, altered photographs, hand-sewn dolls, home installations and sculptural environments. She was said to have an "instinctive understanding of the relation between color and form." Her work focuses on race, gender, domesticity, African-American folklore, and spiritual traditions.

William Sidney Arnett was an Atlanta-based writer, editor, curator and art collector who built internationally important collections of African, Asian, and African American art. Arnett was the founder and chairman of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an organization dedicated to the preservation and documentation of African American art from the Deep South that works in coordination with leading museums and scholars to produce groundbreaking exhibitions and publications using its extensive holdings. His efforts produced 13 books with nearly 100 essays by 73 authors. Thirty-eight museums have hosted major exhibitions, and comprehensive archives are maintained at UNC Chapel Hill. The White House has shown the collection. Arnett exhibited works from these collections and delivered lectures at over 100 museums and educational institutions in the United States and abroad. He is perhaps best known for writing about and collecting the work of African American artists from the Deep South. Arnett was named one of the "100 Most Influential Georgians" by Georgia Trend Magazine in January 2015. He died on August 12, 2020.

Souls Grown Deep Foundation is a non-profit organization dedicated to documenting, preserving, and promoting the work of leading contemporary African American artists from the Southeastern United States. Its mission is to include their contributions in the canon of American art history through acquisitions from its collection by major museums, as well as through exhibitions, programs, and publications. The foundation derives its name from a 1921 poem by Langston Hughes (1902–1967) titled "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," the last line of which is "My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

"Missionary" Mary L. Proctor is an American artist, best known for her visionary paintings, collages, and assemblages.

Juanita Rogers was a self-taught American folk artist. She was born in Tintop, Alabama to Thomas and Sally Rogers, although she claimed she was adopted after arriving in North Montgomery by carnival train at the age of five. Her mother was part Creek Indian, and died when Juanita was about twenty. Juanita attended a Catholic mission school. She was married to Sol Huffman, who died in 1980.

Lucy Marie (Young) Mingo is an American quilt maker and member of the Gee's Bend Collective from Gee's Bend (Boykin), Alabama. She was an early member of the Freedom Quilting Bee, which was an alternative economic organization created in 1966 to raise the socio-economic status of African-American communities in Alabama. She was also among the group of citizens who accompanied Martin Luther King Jr. on his 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Willie Abrams (1897–1987), also known as Ma Willie, was an American artist. She was a member of the Freedom Quilting Bee, along with her daughter Estelle Witherspoon, and is associated with the Gee's Bend quilters. Her work is included in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gearldine Westbrook (1919–2016) was an American artist associated with the Gee's Bend group of quilters.

Delia Bennet (1892–1976) was an American artist. She is associated with the Gee's Bend quilting collective, and is said to be "the matriarch of perhaps the largest family of quilt producers in Gee's Bend. Her work is included in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Sue Willie Seltzer (1922–2010) was an American artist. She is associated with the Gee's Bend quilting collective. Her work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the National Gallery of Art, and is included in the collection of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Irene Williams (1920–2015) was an American artist. She is associated with the Gee's Bend quilting collective, although she made her quilts "in solitude" and "uninfluenced." Her work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Frist Art Museum, and is included in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the National Gallery of Art.

Magalene Wilson (1898–2001), also known as Magdalene Wilson, was an American artist. She is associated with the Gee's Bend quilting collective. Her work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and is included in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Mertlene Perkins (1917–2015) was an American artist. She is associated with the Gee's Bend quilting collective. Her work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and is included in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Amelia Bennett (1914–2002) was an American artist. She is associated with the Gee's Bend quilting collective. Her work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and is included in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art.

Emmer Sewell is an African-American contemporary artist. Sewell is known for her sculptures made of found objects. Her work is included in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Leroy Almon (1938–1997) was an American artist known for his woodcarvings and paintings.

Joe Louis Light (1934–2005) was an American painter from Dyersburg, Tennessee. His work focuses on transcendentalism, attaining spiritual or moral enlightenment, and the balance and order of the universe.

Charlie Lucas is a contemporary sculptor born in Pink Lily, Alabama, who now lives and works in Selma, Alabama. He is owner and operator of the Tin Man Studio, part gallery and part studio, in Selma.