The Selective Service System (SSS) is an independent agency of the United States government that maintains information on U.S. citizens and other U.S. residents potentially subject to military conscription and carries out contingency planning and preparations for two types of draft: a general draft based on registration lists of men aged 18–25, and a special-skills draft based on professional licensing lists of workers in specified health care occupations. In the event of either type of draft, the Selective Service System would send out induction notices, adjudicate claims for deferments or exemptions, and assign draftees classified as conscientious objectors to alternative service work. All male U.S. citizens and immigrant non-citizens who are between the ages of 18 and 25 are required by law to have registered within 30 days of their 18th birthdays, and must notify the Selective Service within ten days of any changes to any of the information they provided on their registration cards, such as a change of address. The Selective Service System is a contingency mechanism for the possibility that conscription becomes necessary.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court which held that "a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China", automatically became a U.S. citizen at birth. This decision established an important precedent in its interpretation of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Clinton v. City of New York, 524 U.S. 417 (1998), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 6–3, that the line-item veto, as granted in the Line Item Veto Act of 1996, violated the Presentment Clause of the United States Constitution because it impermissibly gave the President of the United States the power to unilaterally amend or repeal parts of statutes that had been duly passed by the United States Congress. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the six-justice majority that the line-item veto gave the President power over legislation unintended by the Constitution, and was therefore an overstep in their duties.

In the United States, military conscription, commonly known as the draft, has been employed by the U.S. federal government in six conflicts: the American Revolutionary War, the American Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. The fourth incarnation of the draft came into being in 1940, through the Selective Training and Service Act; this was the country's first peacetime draft. From 1940 until 1973, during both peacetime and periods of conflict, men were drafted to fill vacancies in the U.S. Armed Forces that could not be filled through voluntary means. Active conscription in the United States ended in 1973, when the U.S. Armed Forces moved to an all-volunteer military. However, conscription remains in place on a contingency basis; all male U.S. citizens, regardless of where they live, and male immigrants, whether documented or undocumented, residing within the United States, who are 18 through 25 are required to register with the Selective Service System. United States federal law also continues to provide for the compulsory conscription of men between the ages of 17 and 44 who are, or who have made a declaration of intention to become, U.S. citizens, and additionally certain women, for militia service pursuant to Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution and 10 U.S. Code § 246.

United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court, ruling that a criminal prohibition against burning a draft card did not violate the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech. Though the court recognized that O'Brien's conduct was expressive as a protest against the Vietnam War, it considered the law justified by a significant government interest unrelated to the suppression of speech and was tailored towards that end.

"The Constitution is not a suicide pact" is a phrase in American political and legal discourse. The phrase expresses the belief that constitutional restrictions on governmental power must be balanced against the need for survival of the state and its people. It is most often attributed to Abraham Lincoln, as a response to charges that he was violating the United States Constitution by suspending habeas corpus during the American Civil War. Although the phrase echoes statements made by Lincoln, and although versions of the sentiment have been advanced at various times in American history, the precise phrase "suicide pact" was first used in this context by Justice Robert H. Jackson in his dissenting opinion in Terminiello v. Chicago, a 1949 free speech case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. The phrase also appears in the same context in Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, a 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision written by Justice Arthur Goldberg.

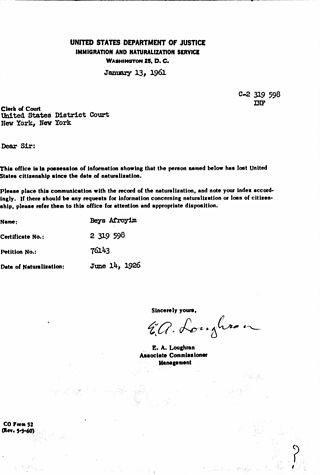

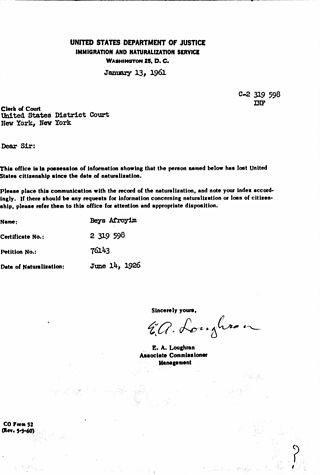

Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled that citizens of the United States may not be deprived of their citizenship involuntarily. The U.S. government had attempted to revoke the citizenship of Beys Afroyim, a man born in Poland, because he had cast a vote in an Israeli election after becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen. The Supreme Court decided that Afroyim's right to retain his citizenship was guaranteed by the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In so doing, the Court struck down a federal law mandating loss of U.S. citizenship for voting in a foreign election—thereby overruling one of its own precedents, Perez v. Brownell (1958), in which it had upheld loss of citizenship under similar circumstances less than a decade earlier.

Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57 (1981), is a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States holding that the practice of requiring only men to register for the draft was constitutional. After extensive hearings, floor debate and committee sessions on the matter, the United States Congress reauthorized the law, as it had previously been, to apply to men only. Several attorneys, including Robert L. Goldberg, subsequently challenged the Act as gender distinction. In a 6–3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the Act, holding that its gender distinction was not a violation of the equal protection component of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Perez v. Brownell, 356 U.S. 44 (1958), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court affirmed Congress's right to revoke United States citizenship as a result of a citizen's voluntary performance of specified actions, even in the absence of any intent or desire on the person's part to lose citizenship. Specifically, the Supreme Court upheld an act of Congress which provided for revocation of citizenship as a consequence of voting in a foreign election.

Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court decision that established that a United States citizen cannot have his or her citizenship taken away unless he or she has acted with an intent to give up that citizenship. The Supreme Court overturned portions of an act of Congress which had listed various actions and had said that the performance of any of these actions could be taken as conclusive, irrebuttable proof of intent to give up U.S. citizenship. However, the Court ruled that a person's intent to give up citizenship could be established through a standard of preponderance of evidence — rejecting an argument that intent to relinquish citizenship could only be found on the basis of clear, convincing and unequivocal evidence.

Nguyen v. INS, 533 U.S. 53 (2001), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the validity of laws relating to U.S. citizenship at birth for children born outside the United States, out of wedlock, to an American parent. The Court declined to overturn a more restrictive citizenship requirement applying to a foreign-born child of an American father and a non-American mother who was not married to the father, as opposed to a child born to an American mother under similar circumstances.

Schneider v. Rusk, 377 U.S. 163 (1964), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case which invalidated a law that treated naturalized and native-born citizens differentially under the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Nishikawa v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 129 (1958), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled that a dual United States/Japanese citizen who had served in the Japanese military during World War II could not be denaturalized unless the United States could prove that he had acted voluntarily.

The Selective Service Act of 1948, also known as the Elston Act, was a United States federal law enacted June 24, 1948, that established the current implementation of the Selective Service System.

Rogers v. Bellei, 401 U.S. 815 (1971), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court, which held that an individual who received an automatic congressional grant of citizenship at birth, but who was born outside the United States, may lose his citizenship for failure to fulfill any reasonable residence requirements which the United States Congress may impose as a condition subsequent to that citizenship.

The Immigration and Nationality Technical Corrections Act of 1994, Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law 103–416, 108 Stat. 4305, enacted October 25, 1994, was an act by the United States Congress "to amend title III of the Immigration and Nationality Act to make changes in the laws relating to nationality and naturalization." Introduced by Romano Mazzoli, the act amended the Immigration and Nationality Act by allowing the acquisition of United States citizenship from either parent for persons born abroad to parents, only one of whom is a United States citizen.

Thomas Glenn Jolley was an anti-Vietnam War protester who renounced his U.S. citizenship in Canada. Soon after his renunciation, Jolley crossed back into the U.S. and began working in Florida. A U.S. federal court ruled that he was deportable, but the Immigration and Naturalization Service could not actually deport him to Canada because he had lost his Canadian-landed immigrant status. He died in Asheville, North Carolina, at the age of 70.

The Nationality Act of 1940 revised numerous provisions of law relating to American citizenship and naturalization. It was enacted by the 76th Congress of the United States and signed into law on October 14, 1940, a year after World War II had begun in Europe, but before the U.S. entered the war.

Under United States federal law, a U.S. citizen or national may voluntarily and intentionally give up that status and become an alien with respect to the United States. Relinquishment is distinct from denaturalization, which in U.S. law refers solely to cancellation of illegally procured naturalization.

American Samoa consists of a group of two coral atolls and five volcanic islands in the South Pacific Ocean of Oceania. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1830 by British missionaries, who were followed by explorers from the United States, in 1839, and German traders in 1845. Based upon the Tripartite Convention of 1899, the United States, Great Britain, and Germany agreed to partition the islands into German Samoa and American Samoa. Though the territory was ceded to the United States in a series of transactions in 1900, 1904, and 1925, Congress did not formally confirm its acquisition until 1929. American Samoans are non-citizen nationals of the United States. Non-citizen nationals do not have full protection of their rights, though they may reside in the United States and gain entry without a visa. Territorial citizens do not have the ability for full participation in national politics and American Samoans cannot serve as officers in the US military or in many federal jobs, are unable to bear arms, vote in local elections, or hold public office or civil-service positions even when residing in a US state. Nationality is the legal means in which inhabitants acquire formal membership in a nation without regard to its governance type. Citizenship is the relationship between the government and the governed, the rights and obligations that each owes the other, once one has become a member of a nation.